Context: This article is based on the news “Farm and Food Policy: How Modi government has swung from pro-producer to pro-consumer in the last two years” which was published in the Indian Express. From 2014, the Indian government focused on pro-producer policies, emphasizing agricultural growth and farmer welfare. However, in recent years, a policy shift occurred, transforming the approach to pro-consumer measures.

Impact of Farm and Food Policy Shift: Export Boost and Import Reduction

- In the last decade, India witnessed surplus agricultural production leading to low commodity prices and government stockpiles of rice, wheat, and sugar reached record levels.

- To address this, initiatives were taken to boost exports, promote alternative uses of agricultural commodities, and reduce import reliance.

- However, the Indian government responded to shifting economic dynamics by prioritizing consumer interests over producers.

- Post Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, rising food inflation compelled a change in focus.

- During the COVID-induced lockdown, the government doubled monthly food grain allocations under the public distribution system.

Must Read: State Of Food And Agriculture Report 2023

Relation Between Farm and Food Policy and Inflation in India

- Inflation: It is the general rise in prices of goods and services within a particular economy wherein, the purchasing power of consumers decreases, and the value of the cash holdings erodes.

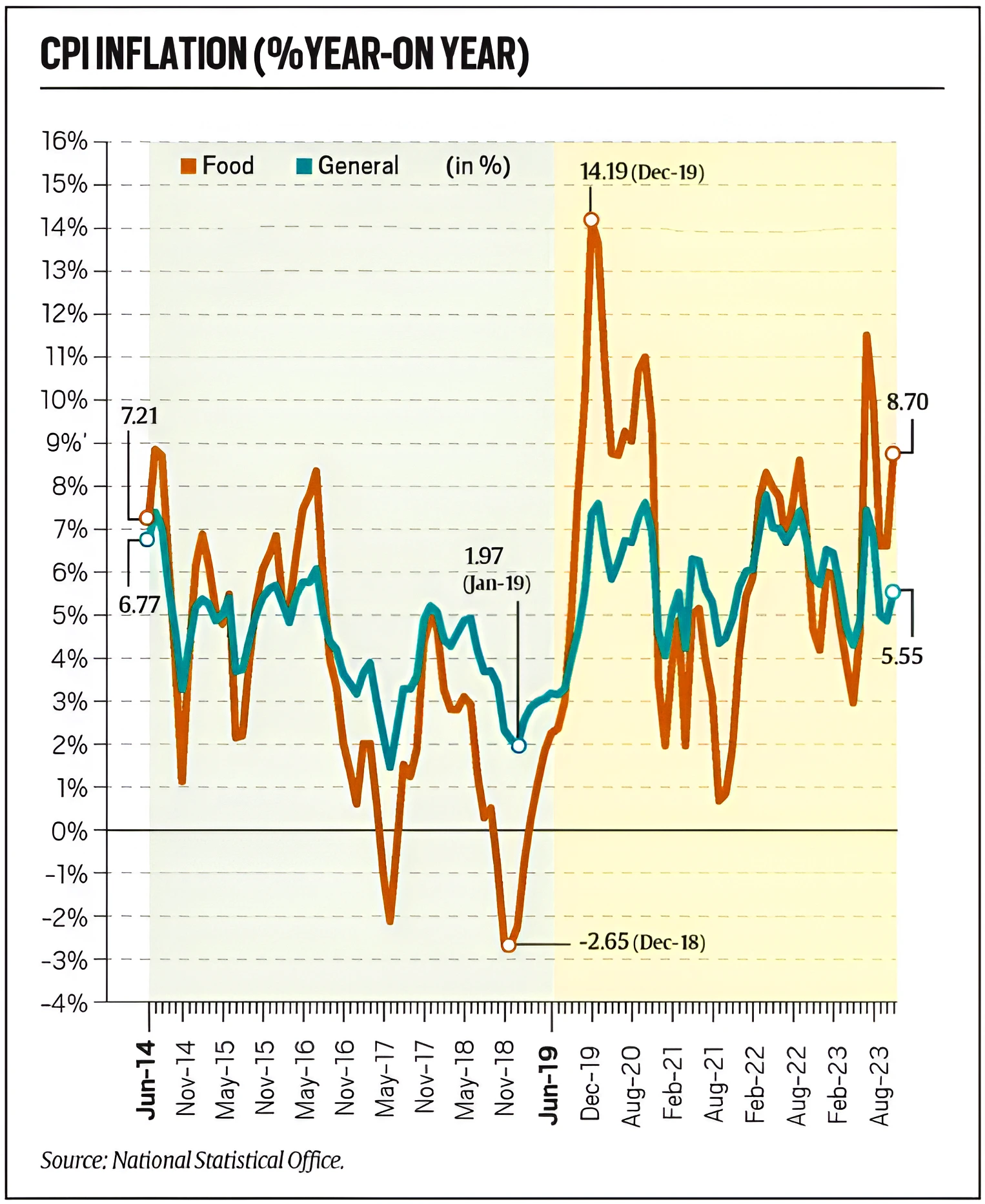

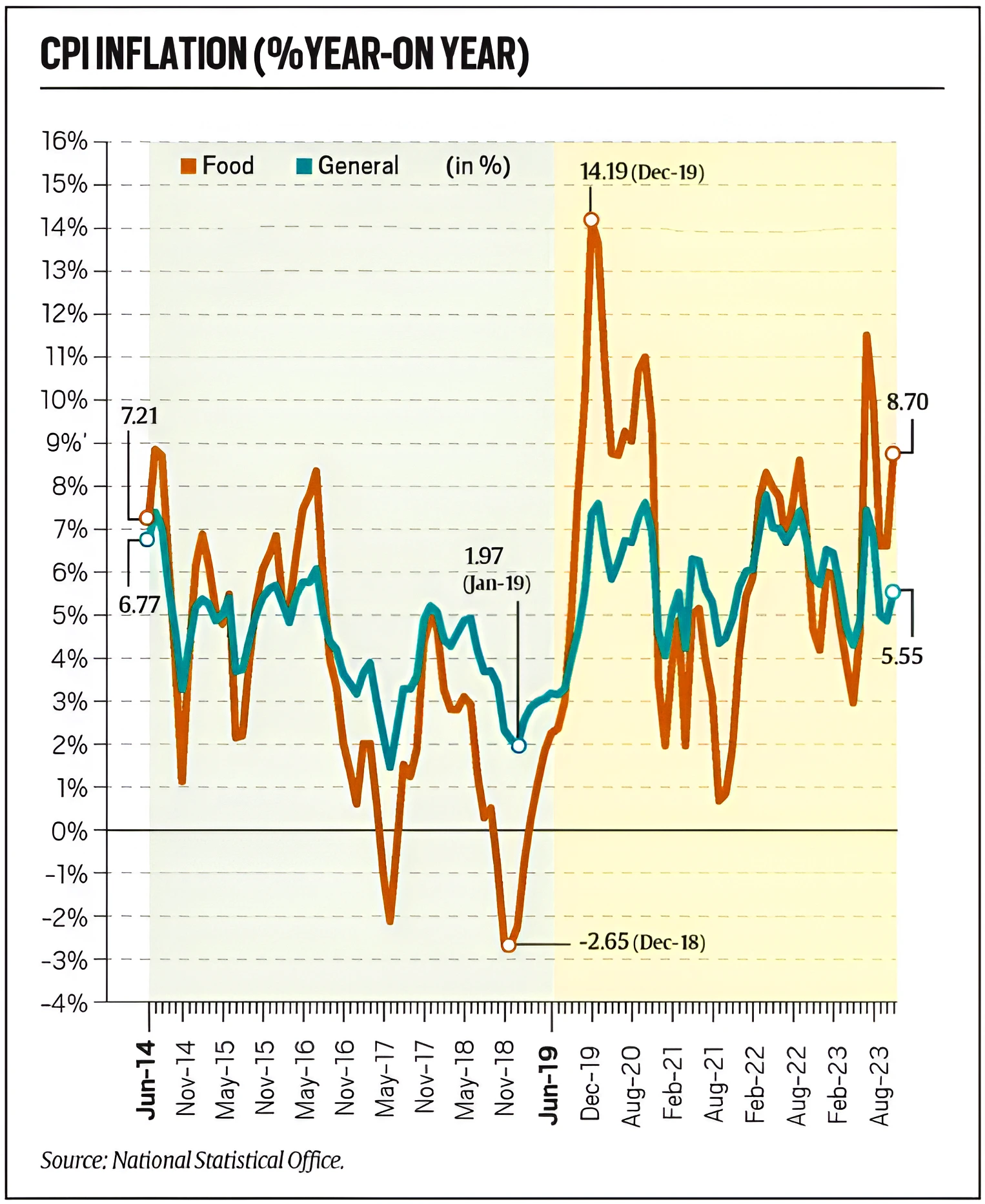

- The government’s policies, from 2014 to 2019, were marked by low inflation.

- During this period, the general consumer price index (CPI) rose by an average of 4.3% per year.

- The consumer food price index (CFPI) was 3.3%.

- The government’s policies, from 2019 to 2023, have seen CPI inflation average 5.8% and 6.4%, for CFPI inflation.

About Inflation

- Inflation Measurement: In India, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) measures inflation.

- In India, inflation is primarily measured by two main indices viz WPI (Wholesale Price Index) and CPI (Consumer Price Index), which measure wholesale and retail-level price changes, respectively.

- CPI: It calculates the difference in the price of commodities and services such as food, medical care, education, electronics etc, which Indian consumers buy for use.

- WPI: The goods or services sold by businesses to smaller businesses for selling further is captured by the WPI.

- Some causes that lead to inflation are: Increase in demand, reduction in supply, demand-supply gap, excess circulation of money, increase in input costs, devaluation of currency, rise in wages, among others.

|

Farm and Food Policy Response During Food Surpluses and Low Prices

- Surplus Production & Low Prices: India experienced a significant surplus in agricultural production, leading to excess supply. This surplus, coupled with inadequate storage and distribution infrastructure, contributed to low prices for various agricultural commodities.

- This period witnessed a record rice and wheat procurement at minimum support prices (MSP), resulting in their stocks in government godowns peaking at 109.5 million tonnes (mt) on July 1, 2021.

- Increasing Exports: The surplus production created an opportunity for increased agricultural exports as lower prices made Indian agricultural products more competitive in the global market, resulting in a boost in exports.

- The government also took initiatives to promote overseas trade. For instance, to enable sugar mills to liquidate their excess stocks, an incentive of up to Rs 10,448 per tonne was given on exports and India shipped out unprecedented quantities of 5.9 mt, 7.2 mt and 11 mt during the 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22 seasons.

- Promoting Alternative Uses: Industries like biofuels, textiles, and pharmaceuticals began to leverage surplus crops, promoting diversification. Government initiatives also encouraged innovation in utilizing agricultural produce for non-traditional purposes.

- For instance, mills were incentivized to produce less sugar from their cane and more ethanol for blending with petrol. Government encouraged this by pushing oil companies to pay more for ethanol made from direct sugarcane juice or intermediate stage (B-heavy) molasses, as against the final residual (C-heavy) molasses.

- Reducing Import Reliance: Lower commodity prices made Indian agricultural products economically competitive, further reducing dependence on external sources, which highlighted the potential for increased self-reliance.

- Further, the government raised import duties on pulses and edible oils to protect domestic growers suffering low realizations.

- For instance, prior to June 30, 2017, pulses imports attracted zero duty and by the end of 2017, there was a 30% duty on masoor and chana (chickpea), 50% on yellow/white peas, and annual import quantity restrictions of 0.2 mt on arhar and 0.3 mt on urad/moong (black/green gram).

- In edible oils, the basic customs duty was increased from 12.5% to 35% on imported crude soyabean and sunflower oil, and from 7.5% to 44% on crude palm oil, between September 2016 and June 2018.

- Introduction of Farm Reform Laws in 2020: The surpluses of this period lead to the government’s enactment of its three farm reform laws in June 2020 which freed the trade in agricultural produce.

- For instance, private agri-businesses could bypass government-regulated markets and buy directly from farmers, with no barriers to movement or limits to how much produce they could purchase and stock.

Reasons for Shifting Farm and Food Policy Dynamics

- Changes in Inflation Trends: The food inflation rose, especially post Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, pushed the transformation of the government’s policy approach, to privilege the interests of consumers over producers.

- Covid- Induced Lockdown: The surpluses, amid the Covid-induced economic shock, led the government to double the monthly allocation of foodgrains under the public distribution system to 10 kg per person during April 2020-December 2022, with the additional 5 kg being given free of cost.

- Liberalisation of Imports: From around November 2020, the customs duty on crude palm, soya bean and sunflower oil was reduced in stages to nil, the same on refined oils was reduced to 12.5%.

- In pulses, the quantity restrictions on imports of arhar and urad were lifted and their imports, including masoor, have been made duty-free.

- Exports Restrictions: Agricultural exports from India faced curbs, which include export duties, minimum export price, and even outright bans.

- For instance, the government has banned exports of wheat and sugar since May 2022 and May 2023 respectively. Only basmati and parboiled non-basmati shipments are permitted in rice, subject to a $950/tonne minimum export price stipulation and 20% duty respectively.

- Prioritising Essential Usage: Recently, sugar mills have been allowed to use cane juice and B-molasses for making ethanol only to the extent that 1.7 mt of sugar gets diverted during the current 2023-24 season, down from 4.5 mt in 2022-23. Thus, the government is prioritizing to ensure that more cane goes for food (sugar) than for fuel (ethanol).

Changing Farm and Food Policy Dynamics and Current Challenges

- Supply Situation: The supply situation changed from surplus to tight with public warehouses having only 62.8 mt of rice and wheat as of December 1, 2023, while sugar mills ended the 2022-23 season with a six-year-low stocks of 5.7 mt.

- Inflation Remains a Challenge: The latest annual retail food inflation number for November 2023 stood at 8.7%, which is even higher at 10.3% for cereals and 20.2% for pulses. Thus, the above restrictions are likely to remain.

- Hampers Agri-Exports: Restrictive export policy hampers the dream of doubling India’s agri exports, a target set out by the government. Further, these restrictions have expanded to wheat export bans, an export duty of 40% on onions, etc.

Way Forward

- Mitigation of Inflation: Indian agriculture has reached a stage where management of surplus production and exports are essential to maintain domestic prices and enhance farmers’ income.

- Further, implement measures to mitigate inflationary pressures, such as judiciously addressing supply chain bottlenecks and using monetary tools.

- Long-Term Vision: A long-term strategy focusing on global market and competitiveness, infrastructure modernization, etc. The Government has taken steps in this direction, but prioritization of the markets and products by agencies like APEDA is necessary for immediate gains.

- Re-thinking Farm and Food Policy in the Digital Age: Breakthrough digital technologies can potentially deliver significant positive impacts for producers, consumers, and the environment, across food value chains.

-

- Further, applying digital technology to manage the supply chains and trace the origin should be in place.

- Reorienting Consumer Welfare Programs: Subsidies to the agricultural sector should be reoriented to focus on productivity and sustainability.

-

- For instance, Direct Benefits Transfer (DBT) programs should be linked to improve resource-use efficiency, economize the cost, and promote conservation of natural resources.

Conclusion:

The shift in Indian farm and food policy, from pro-producer to pro-consumer, aimed at addressing surplus production and low prices. however, it has resulted in challenges in supply, inflation, and agri-exports, emphasizing the need for a balanced and adaptable approach.

![]() 2 Jan 2024

2 Jan 2024