Context: The President has given her assent to three new criminal law reform bills recently approved by Parliament.

| Relevancy for Prelims: Bharatiya Nyaya (Second) Sanhita, 2023, Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita, 2023, Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act 2023, Committee on Criminal Law Reform, Parliamentary Standing Committee, and NCRB Report 2022 On Crime In India.

Relevancy for Mains: Key Highlights of Bharatiya Nyaya (Second) Sanhita, 2023, Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita, 2023, Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act 2023, and History of the Criminal Justice System in India. |

What are the three new criminal laws?

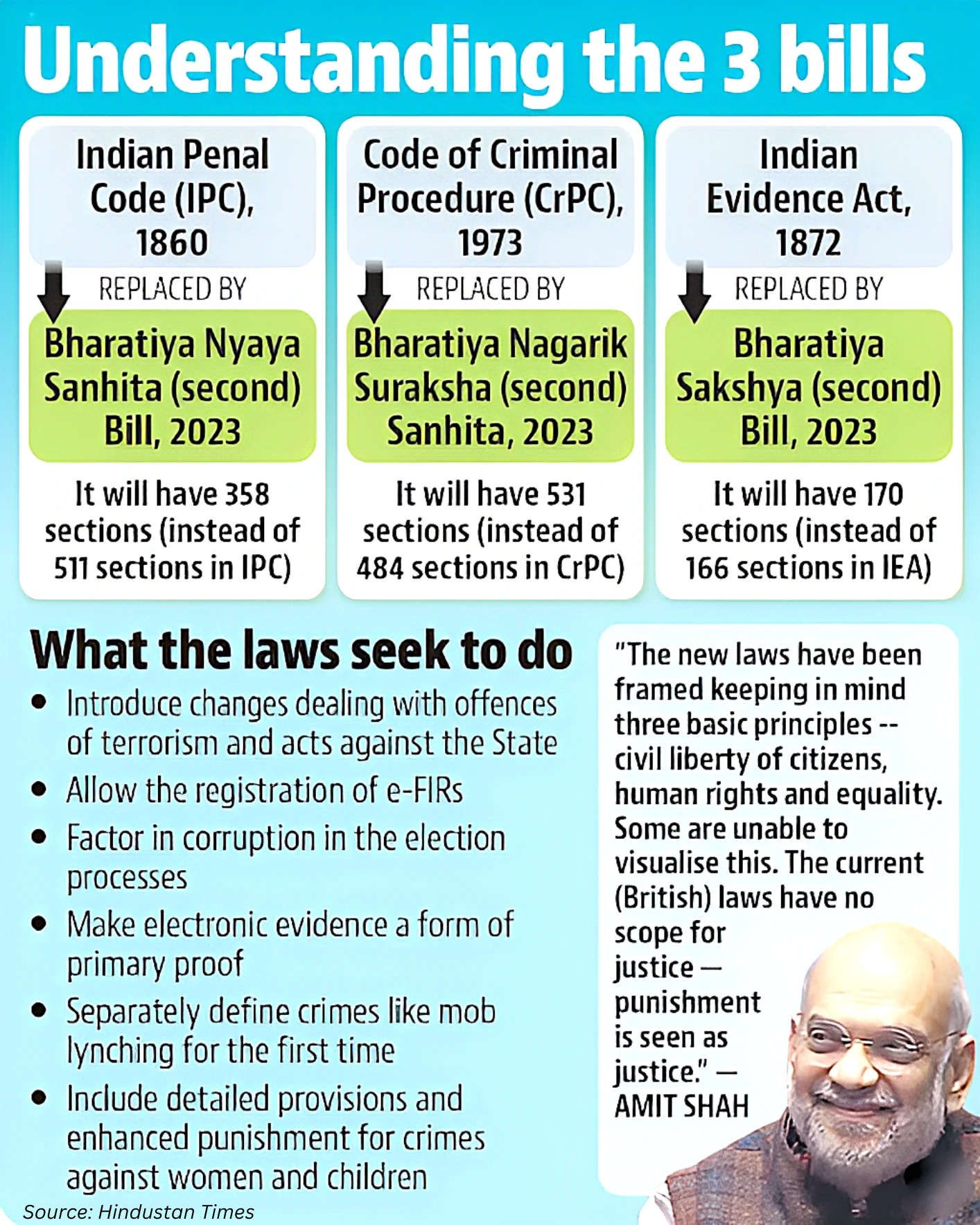

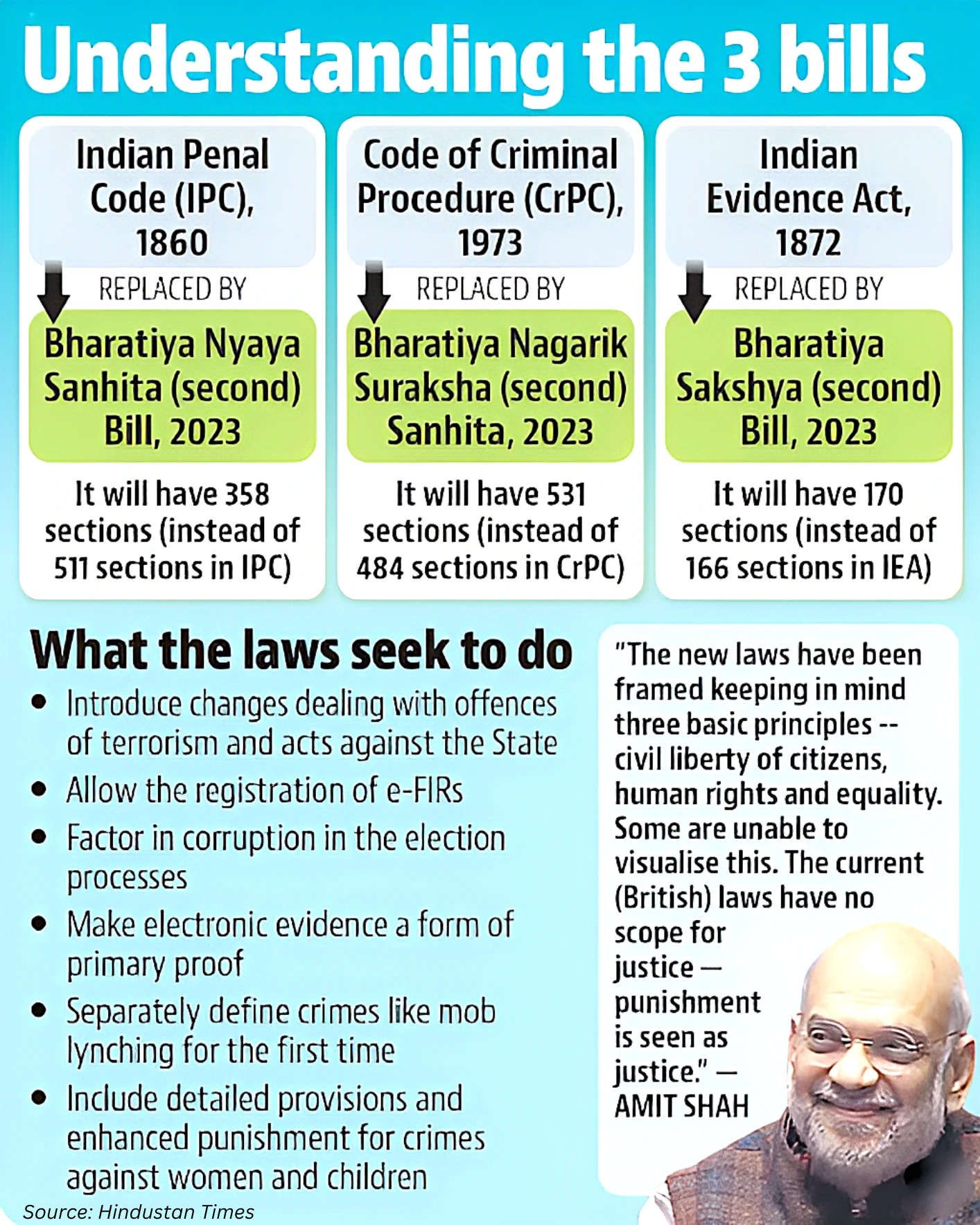

- The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, and Bharatiya Sakshya Act will replace the colonial-era Indian Penal Code, Code of Criminal Procedure, and Indian Evidence Act of 1872.

- These laws aim to overhaul the criminal justice system by providing clear definitions of various offences and punishments.

- Criminal law and criminal procedure fall under the Concurrent List of the Indian Constitution.

- The bills were first introduced during the Monsoon session of Parliament in August 2024 following which, they were referred to a 31-member Parliamentary Standing Committee.

- After the Standing Committee on Home Affairs made several recommendations, the government withdrew the bills and introduced their redrafted versions in the Lok Sabha on December 12.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

History of the Criminal Justice System in India

- British Rule and Codification: Criminal laws were codified, and this framework largely persists into the present day.

- Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay shaped India’s criminal laws during British rule.

- He is often regarded as the chief architect of the codification of criminal laws in India.

Committee on Criminal Law Reform

- The Ministry of Home Affairs in India, on May 4, 2020, established a committee to review and recommend reforms to the three majorl codes of criminal law that constitute the foundation of India’s legal system.

- Headed by: Prof. (Dr.) Ranbir Singh, former Vice Chancellor of National Law University (NLU), Delhi

- Mandate of the Committee: To assess and suggest changes to the Indian Penal Code (IPC), the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and the Indian Evidence Act.

Why did the Government introduce three new criminal laws?

- Colonial Legacy: The three proposed bills seek to modernise and streamline the complex and obsolete criminal law.

- The changes will reflect the evolving nature of crime, society, and technology, as well as bring the laws closer to the spirit and ethos of India.

- Section 124A is a relic of colonial legacy which is unsuited in a democracy as it puts restraint on the legitimate exercise of constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech and expression.

- Misuse of Sedition Law: Sedition (Section 124A) under Indian Penal Code has been misused to persecute political dissent.

- As per the data released by the National Crime Records Bureau, between 2014 and 2016, a total of 179 arrests for sedition have been made under the title ‘offences against the State’ .

- Pendency and Delay: The existing complex procedures of IPC, CrPC, and Indian Evidence Act have contributed to substantial court backlogs and delayed justice delivery.

- As of December 31, 2022, the total pending cases in district and subordinate courts was pegged at over 4.32 crore.

- Low Conviction Rates: The prevailing legal framework has resulted in a low conviction rate, highlighting the need for reforms to enhance the efficacy of criminal proceedings.

- According to the NCRB report 2022, on an all-India basis, the total conviction rate for IPC crimes stood at 57%.

- Overcrowded Prisons and Undertrials: The present system has led to overcrowded jails and a significant number of undertrial prisoners awaiting their trials.

- According to a report on prison statistics for 2019 released by NCRB, there were 4,78,600 inmates lodged in different prisons in India while they had a capacity to 4,03,700 inmates.

- Modernisation and Liberalisation of Criminal Justice System: By enabling citizens to file a police complaint at any police station, regardless of the location where the crime occurred, reforms will empower citizens.

- It will effectively safeguard citizens’ fundamental rights, including the rights to life, liberty, dignity, privacy, and a fair trial.

- Retributive to Restorative Justice: The Colonial justice system merely focused on punishing the criminals rather than taking measures to rehabilitate and introducing measures for protection of victims.

About Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS)

- Offences against the Body: BNS retains the provisions of the IPC which criminalizes acts such as murder, abetment of suicide, assault and causing grievous hurt.

- It adds new offences such as organised crime, terrorism, and murder or grievous hurt by a group on certain grounds.

The Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860: It is the principal law on criminal offences in India.

- Offences covered include those affecting: (i) human body such as assault and murder, (ii) property such as extortion and theft, (iii) public order such as unlawful assembly and rioting, (iv) public health, safety, decency, morality, and religion, (iv) defamation, and (v) offences against the state.

|

- Sexual offences against women: It increases the threshold for the victim to be classified as a major, in the case of gang rape, from 16 to 18 years of age.

- It also criminalises sexual intercourse with a woman by deceitful means or making false promises.

- Remove Sedition (Rajdroh): The BNS removes the offence of sedition. It instead penalises the following:

-

- Exciting or attempting to excite secession, armed rebellion, or subversive activities,

- Encouraging feelings of separatist activities, or

- Endangering the sovereignty or unity and integrity of India.

- These offences may involve the exchange of words or signs, electronic communication, or the use of financial means.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Classes

- Terrorism: Section 113 of the BNS modified the definition of the crime of terrorism to adopt the existing definition under Section 15 of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967(UAPA).

- Terrorism includes an act that intends to:

-

- Threaten the unity, integrity, security or economic security of the country, or

- Strike terror in the people or any section of people in India.

- Punishment for attempting or committing terrorism includes:

- Death or life imprisonment, and a fine if it results in the death of a person or

- Imprisonment between five years and life, and a fine.

- Difference of Terrorist Act under BNS from UAPA: Terrorist acts under the UAPA include the production or smuggling or circulation only of high-quality counterfeit Indian paper currency, coin or any other material within the ambit of terrorism.

- The BNS widens this definition to cover the same activities with respect to any counterfeit Indian paper currency, coin or of any other material.

- Offence for training terrorists: The offence of recruiting and training persons to engage in terrorist acts has been introduced, resembling sections 18A and 18B of the UAPA.

- Organised Crime: It includes offences such as kidnapping, extortion, contract killing, land grabbing, financial scams, and cybercrime carried out on behalf of a crime syndicate.

- Attempting or committing organised crime will be punishable with:

- Death or life imprisonment and a fine of Rs 10 lakh, if it results in death of a person, or

- Imprisonment between five years and life, and a fine of at least five lakh rupees.

- Mob Lynching: It adds murder or grievous hurt by five or more people on specified grounds, as an offence. These grounds include race, caste, sex, language, or personal belief.

- The punishment for such murder is life imprisonment or death.

- Criminalisation of Suicides Impacting Official Discharge of Duties: It criminalizes any attempt of suicide with the intent to compel or restrain any public servant from discharging official duties.

- It prescribes a jail term of up to one year along with community service. This provision may be invoked to prevent self-immolations and hunger strikes during protests.

- Fake Speech: The IPC includes Section 153B for addressing the “hate speech” provision. This section criminalizes, causing “disharmony or feelings of enmity or hatred or ill-will” between communities.

- The BNS introduces a new provision for criminalizing the publication of false and misleading information.

- Rulings of the Supreme Court: The BNS conforms to some decisions of the Supreme Court.

- These include omitting adultery as an offence and adding life imprisonment as one of the penalties (in addition to the death penalty) for murder or attempt to murder by a life convict.

- Unauthorised publication of court proceedings: Section 73 provides punishment of two-year jail sentence and a fine for printing or publishing ‘any matter’ concerning court proceedings in rape or sexual assault cases without permission.

- Reports on High Court or Supreme Court judgments would not amount to an offence within this provision.

- Mental illness replaced by unsoundness of mind: It replaces the term ‘mental illness’ with ‘unsoundness of mind’ in a majority of the provisions as the term ‘mental illness’ is too wide and may even include mood swings and voluntary intoxication. .

- The term ‘intellectual disability’ has been added along with unsoundness of mind in section 367 (competence to stand trial).

- Petty organised crime redefined: The revised Bill includes a precise definition of petty organised crime.

- Theft under it would include trick theft, theft from vehicle, dwelling house, or business premises, cargo theft, pickpocketing, theft through card skimming, shoplifting, and theft of Automated Teller Machine.

- Community Service: It adds community service as a punishment. It extends this punishment to offences such as:

- Theft of property worth less than Rs. 5,000,

- Attempt to commit suicide with the intent to restrain a public servant, and

- Appearing in a public place intoxicated and causing annoyance.

Key Challenges with BNS

- Age of Criminal Responsibility: Under IPC, nothing is considered an offense if committed by a child below the age of seven years. The age of criminal responsibility increases to 12 years, if the child is found not to have attained the ability to understand the nature and consequences of his conduct.

- The BNS retains these provisions. This age is lower than the age of criminal responsibility in other countries.

- For instance, in Germany, the age of criminal responsibility is 14 years, whereas in England and Wales, it is 10 years.

- In 2007, a UN Committee recommended that states set the age of criminal responsibility to above 12 years.

- Aspects of Sedition Retained: The new provision retains certain aspects of the offense of sedition and broadens the range of acts that could threaten India’s unity and integrity.

- Terms like ‘subversive activities’ are also not defined, and what activities will meet this qualification is unclear.

- In the Constitution Bench judgment of 1962 in the Kedar Nath Singh versus State of Bihar case, the Supreme Court limited the application of sedition to acts with the intention or tendency to create public disorder or incite violence.

- Solitary Confinement: Provisions on solitary confinement do not align with Court rulings and expert recommendations, it may violate fundamental Rights.

- The Supreme Court ruled in Unni Krishnan & Ors. v. State of Andhra Pradesh & Ors., that the right against solitary confinement is protected under Article 21.

- The Scope of Community Service: It does not define what community service will entail and how it will be administered.

- The Standing Committee on Home Affairs (2023) recommended defining the term and nature of ‘community service.’

- Offences against Women: The BNS retains the provisions of IPC related to rape. It has not addressed several recommendations made by the Justice Verma Committee (2013) and Supreme Court on reforming offences against women.

- For Example: As per IPC s.375 – Rape should not be limited to penetration of the vagina, mouth, or anus. Any non-consensual penetration of a sexual nature should be included in the definition of rape.

- The exception to marital rape should be removed as the marital rape has not been made an offence under BNS.

- Drafting Issues: There are several drafting issues in the BNS.

- Section 377 specifies “intercourse against the order of nature against any man, woman or animal” an offence; the Supreme Court read this down to exclude consensual sex between adults.

The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC):

- The CrPC governs the powers of the police to maintain public order, prevent crimes, and undertake criminal investigations.

- These powers include arrests, detention, search, seizure, and use of force.

- These powers are subject to restrictions to safeguard individuals from misuse of police powers leading to excessive use of force, illegal detentions, custodial torture, and abuse of authority.

|

-

- The BNS does not retain section 377. This implies that rape of an adult man will not be an offence under any law, neither will having intercourse with an animal.

About The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, Act 2023 (BNSS) or The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS)

- It was introduced in Lok Sabha on August 11, 2023 to replace the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC).

- Incorporating some recommendations of the Committee, the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) was introduced on December 12, 2023.

- Key Features: The CrPC governs the procedural aspects of criminal justice in India. The BNSS retains most of the provisions of the CrPC.

- Separation of offences: The CrPC classifies offences into two categories: Cognisable and Non-Cognisable.

- Cognisable offences are those in which the police can arrest and initiate an investigation without a warrant.

- Non-cognisable offences require a warrant, and in some cases, a complaint by the victim or a third party.

- Nature of offences: The CrPC deals with various types of criminal offences, ranging from traffic violations to murder.

- It distinguishes between bailable and non-bailable offences, specifying the offences for which an accused has the right to bail from police custody.

Key Changes Proposed Include

- Detention of Undertrials: As per the CrPC, if an accused has spent half of the maximum period of imprisonment in detention, he must be released on personal bond. This does not apply to offenses punishable by death.

- The BNSS2 adds that this provision will also not apply to:

- Offences punishable by life imprisonment, and

- Persons against whom proceedings are pending in more than one offence.

- Medical Examination: The CrPC allows medical examination of the accused in certain cases, including rape cases. Such examination is done by a registered medical practitioner at the request of at least a Sub-inspector level police officer.

- The BNSS provides that any police officer can request such an examination.

- Forensic Investigation: The BNSS mandates forensic investigation for offenses punishable with at least seven years of imprisonment.

- In such cases, forensic experts will visit crime scenes to collect forensic evidence and record the process on a mobile phone or any other electronic device.

- If a state does not have a forensics facility, it shall utilize it in another state.

- Signatures and finger impressions: The CrPC empowers a Magistrate to order any person to provide specimen signatures or handwriting.

- The BNSS expands this to include finger impressions and voice samples. It allows these samples to be collected from someone who has not been arrested.

- Timelines for procedures: The BNSS prescribes timelines for various procedures.

- For instance, it requires medical practitioners who examine rape victims to submit their reports to the investigating officer within seven days.

- Preventive Detention: Ambiguity in the earlier bill permitted the preventive detention to continue until the person is produced before a Magistrate.

- The revised Bill has introduced a strict timeline i.e., the detained person must be produced before the Magistrate or released in petty cases within 24 hours.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

Key Issues with BNSS

- The Procedure of police Custody altered: The Constitution and CrPC prohibit detention in police custody beyond 24 hours exclusive of the time necessary for the journey from the place of arrest to the magistrate court.

- The Magistrate is empowered to extend it up to 15 days if the investigation cannot be completed within 24 hours.

- The BNSS allows up to 15 days of police custody, which can be authorised in parts during the initial 40 or 60 days of the 60 or 90 days period of judicial custody. This may lead to denial of bail for the entire period if the police has not exhausted the 15 days custody.

- Thus, it expands the maximum limit of police custody under general criminal law from 15 days to either 60 days or 90 days (depending on the nature of the offence) increasing the risk of exposure to police excesses and impacting civil liberties

- The Standing Committee (2023) recommended clarifying this clause’s interpretation.

- The power to use Handcuffs: The BNSS provides for the use of handcuffs during arrest in heinous crimes like rape and murder.

- The power of the police to use handcuffs has been expanded beyond the time of arrest to include the stage of production before court as well.

- The Supreme Court has held that the use of handcuffs is inhumane, unreasonable, arbitrary, and repugnant to Article 21.

- Rights of the Accused: As per the CrPC, if an undertrial has served half the maximum imprisonment for an offence, he must be released on a personal bond. This provision does not apply to offences punishable by death.

- The BNSS retains this provision and adds that first-time offenders get bail after serving one-third of the maximum sentence.

- However, it adds that this provision will not apply to:

- Offences punishable by life imprisonment, and

- Where an investigation, inquiry or trial in more than one offence or in multiple cases are pending.

- For example, Rash and dangerous driving is a punishable offense under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 and the IPC. Upon filing of chargesheets, multiple offenses may make undertrial prisoners ineligible for bail. Scope For Plea Bargaining May Be Limited: Plea bargaining was added to the CrPC in 2005. It is not allowed for offences punishable with a death penalty, life imprisonment, or imprisonment term exceeding seven years. The BNSS retains this provision.

- This limits plea bargaining in India to sentence bargaining, that is getting a lighter sentence in exchange for the accused’s guilty plea.

| Plea bargaining is an agreement between the defense and prosecution where the accused pleads guilty for a lesser offense or a reduced sentence. |

- Safeguards On The Attachment Of Property: The CrPC allows police to seize property. This is applicable only to movable properties.

- The BNSS2 extends this to immovable properties as well.

- The power to attach property from proceeds of crime does not have safeguards provided in the Prevention of Money Laundering Act.

- Overlaps With Existing Laws: Over the years, special laws have been enacted to regulate various aspects of criminal procedure. However, the BNSS retains some of the procedures.

- Under CrPC, a Magistrate may order a person to have sufficient means to make a monthly allowance for the maintenance of their father or mother (who cannot maintain themselves).

| Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022: It allows police officers or prison officers to collect certain identifiable information (such as fingerprints, biological samples) from convicts or those who have been arrested for an offence. |

-

- The BNSS retains this provision, duplicating the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007 provisions.

- Excess Powers to Police: It gives wide powers to the police to arrest, search, seize, and detain without any judicial oversight or safeguards.

- Data Collection For Criminal Identification: With Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022 allowing for data collection of criminals and accused, the need for retaining data collection provisions and expanding on them in the BNSS is unclear.

- The constitutional validity of the 2022 Act is under consideration before the Delhi High Court.

About Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act 2023 (BSB)

- The Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Bill, 2023 was introduced on December 12, 2023 after the earlier Bill was withdrawn.

- It incorporates most of the suggestions made by the Standing Committee on Home Affairs.

The Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (IEA):

- It governs the admissibility of evidence in Indian Courts.

- It applies to all civil and criminal proceedings.

- Over the years, the IEA has been amended to align with certain criminal reforms and technological advancements.

- In 2000, the IEA was amended to provide for the admissibility of electronic records as secondary evidence.

|

Key Features of Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act 2023 (BSB)

The Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act 2023 (BSB) retains most of the provisions of the IEA. These include;

- Admissible Evidence: Parties involved in a legal proceeding can only present admissible evidence. Admissible evidence can be classified as either ‘facts in issue’ or ‘relevant facts.’

- The IEA provides two kinds of evidence documentary and oral evidence.

- Facts in issue refer to any fact that determines the existence, nature, or extent of any right, liability, or disability claimed or denied in a legal proceeding.

- Relevant facts are facts that are pertinent to a given case.

|

- A proved fact: A fact is considered proven when, based on the evidence presented, the Court believes it to either:

- Exist, or

- Its existence is so likely that a prudent man should act as if it exists in circumstances of the case.

- The admissibility of electronic records as evidence: The IEA allows electronic records to be admitted as secondary evidence and specifies the procedure to admit such evidence.

- The BSB amends this to clarify that electronic records produced from proper custody will be considered primary evidence, unless disputed

- Police confessions: Any confession made to a police officer is inadmissible. Confessions made in police custody are also inadmissible, unless recorded by a Magistrate.

- However, if a fact is discovered as a result of information received from an accused in custody, that information may be admitted if it distinctly relates to the fact discovered.

- Documentary Evidence: Under the IEA, a document includes writings, maps, and caricatures.

- The BSB adds that electronic records will also be considered as documents.

- Oral Evidence: Under the IEA, oral evidence includes statements made before Courts by witnesses in relation to a fact under inquiry.

- The BSB allows oral evidence to be given electronically.

- Secondary Evidence: The BSB expands secondary evidence to include: (i) oral and written admissions, and (ii) the testimony of a person who has examined the document and is skilled to examine the documents.

- Joint trials: A joint trial refers to the trial of more than one person for the same offence.

- The BSB adds an explanation to this provision. It states that a trial of multiple persons, where an accused has absconded or has not responded to an arrest warrant, will be treated as a joint trial.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Classes

Key Issues with Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act 2023 (BSB)

- Tampering of electronic records: In 2014, the Supreme Court recognised that electronic records are susceptible to tampering and alteration.

- The Standing Committee on Home Affairs (2023) noted the importance of safeguarding the authenticity and integrity of electronic and digital records as they are prone to tampering.

- Challenges to Facts Discovered in Police Custody: As per the IEA, information obtained from an accused person in police custody can be used as evidence if it directly relates to a discovered fact, this provision is retained in the BSB.

- The Law Commission (2003) recommended that fact discovered in police custody using threat, coercion, violence, or torture should not be provable.

- Admissibility of fact: The BSB retains the provision of IEA that information received from an accused in police custody is admissible if it relates to a fact discovered, whereas similar information is not admissible if it was received from an accused outside police custody.

- The Law Commission (2003) had suggested re-drafting the provision to ensure that information relating to facts should be relevant whether the statement was given in or outside police custody.

- For Example, Malimath Committee: Repeal sections on confessions to police officers (IEA. S.25-29).

Conclusion:

The revised three criminal laws redefine specific offenses while enhancing the penalties for crimes like terrorism, mob violence, offenses against the nation’s security and sovereignty, and various others. However, the true essence of overhauling the criminal justice system might not be fully realized since, achieving lasting change demands not only legislative amendments but also a comprehensive revaluation of institutional cultures and practices, aiming for a more just and effective system.

![]() 28 Dec 2023

28 Dec 2023