Recently the Supreme Court of India highlighted several issues of the Tribunals while hearing a petition challenging constitutional validity of the Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021.

Key Takeaways from Supreme Court’s Observations on Tribunals in India

- Strengthening the Tribunal System: The Supreme Court emphasised the need to strengthen tribunals to maintain litigants’ confidence in the adjudication process.

- The Supreme Court criticized the treatment of retired judges in tribunals and urged the Centre to strengthen transfer and posting mechanisms.

- Issues with Recruitment and Staffing: The recruitment of tribunal members is overseen by a committee led by a Supreme Court judge.

- However, issues like service conditions, recruitment of support staff, and tenure fall under the central government’s domain.

- The Supreme Court highlighted concerns over contract-based employment of support staff in sensitive tribunals like the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT).

- Vacancies in Tribunals: The court previously directed the Centre (in January 2025) to furnish data on vacancies within four weeks.

- The court questioned the age criteria for GST tribunal appointments, which had been invalidated earlier but was reinstated in the 2021 law.

|

Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021

- Background: The Act was enacted to streamline tribunals by dissolving certain appellate tribunals and transferring their functions to existing judicial bodies like High Courts.

- It was introduced in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Madras Bar Association vs. Union of India (2021), which struck down provisions of the Tribunal Reforms Ordinance, 2021.

- Key Provisions

- Abolition of Tribunals: Multiple appellate tribunals were dissolved, and their functions were shifted to High Courts and other judicial bodies.

- Search-cum-Selection Committee: Established to recommend the appointment of tribunal chairpersons and members.

- For Central Tribunals:

- Chairperson: Chief Justice of India (CJI) or a Supreme Court judge nominated by the CJI (casting vote).

- Other Members: Two secretaries nominated by the Central Government, sitting/outgoing chairperson of the tribunal (or a retired Supreme Court judge/Chief Justice of a High Court).

- Non-voting Member: Secretary of the relevant Union Ministry.

- For State Administrative Tribunals: Chairperson: Chief Justice of the respective High Court (casting vote).

- Other Members: Chief Secretary of the State Government, Chairman of the State Public Service Commission, sitting/outgoing tribunal chairperson, or a retired High Court judge.

- Tenure and Age Limits

- Chairperson and members have a 4-year tenure, with a minimum age of 50 years.

- Maximum age limit: 67 years for tribunal members and 70 years for chairpersons, or completion of the 4-year tenure, whichever is earlier.

- Tribunal chairpersons and members are eligible for reappointment, with preference given to past service.

- Removal of Tribunal Members: The Central Government, based on the recommendation of the Search-cum-Selection Committee, can remove a chairperson or member.

Criticism of the Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021

- Reintroduction of Struck-Down Provisions: The Act was introduced in Lok Sabha just days after the Supreme Court struck down the Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021.

- It reinstated the same provisions that the Supreme Court had declared unconstitutional without addressing the court’s concerns.

- Threat to Judicial Independence: The Act grants the government extensive control over appointments, service conditions, and salaries of tribunal members.

- This undermines the independence of tribunals and raises concerns about executive overreach.

- Abolition of Key Tribunals: The Act abolished nine important tribunals, transferring their functions to High Courts or other judicial bodies.

- This has raised concerns about overburdening courts and reducing specialized adjudication.

- Tenure and Appointment Challenges: The four-year tenure under the 2021 Act has discouraged good candidates from joining tribunals.

- Lack of Parliamentary Debate: The Act was passed amidst disruptions in Parliament without adequate discussion. Critics argue this bypassed the necessary legislative scrutiny for such a significant reform.

Global Structure of Tribunal system

- Australia: Handles administrative and civil matters. Appeals go to the Court of Appeal, under the Supreme Court.

- United Kingdom: Two-tier system:

- First-Tier Tribunal – Multiple Chambers by subject.

- Upper Tribunal – Hears appeals.

- Appeals proceed to the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court.

- The Employment Appeals Tribunal exists separately.

- Managed by HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS).

- United States: Tribunals have quasi-judicial powers only.

- Judicial powers remain with courts per the Constitution.

- Tribunal decisions are subject to judicial review.

|

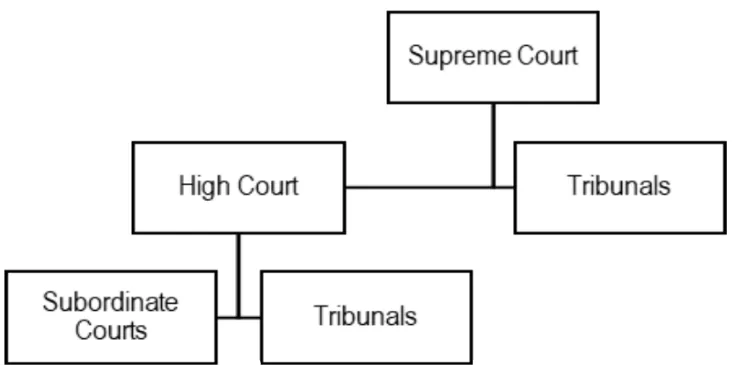

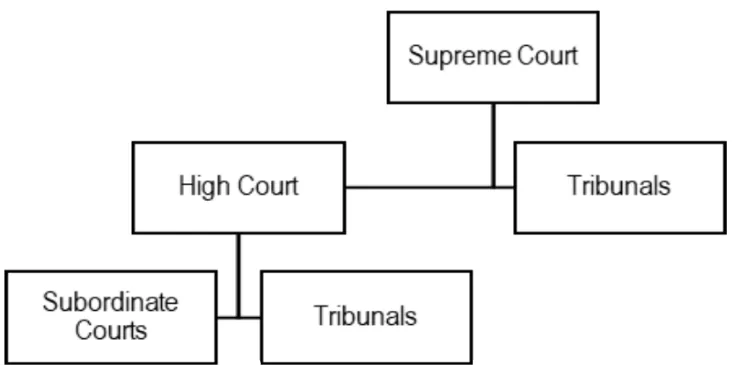

About Tribunals

- A tribunal is a quasi-judicial body that resolves disputes related to administration, taxation, environment, securities, and other specialized areas.

- Tribunals as an Alternative to Courts: Tribunals in India serve as adjudicatory bodies offering an alternative to the traditional court system.

- Functions of Tribunals

- Adjudicating Disputes: Settling legal conflicts between parties.

- Determining Rights: Deciding entitlements and obligations of contesting parties.

- Administrative Decisions: Making rulings on policy implementation and enforcement.

- Reviewing Decisions: Reassessing existing administrative decisions for fairness and legality.

Difference Between Tribunal and Court

| Feature |

Tribunal |

Court |

| Nature |

Specialized adjudicatory body |

General judicial authority |

| Jurisdiction |

Specific subject matter (e.g., tax, labor, environment) |

Broad jurisdiction over civil, criminal, and constitutional matters |

| Composition |

Includes judicial and technical members |

Composed of judges with legal backgrounds |

| Procedures |

Less formal, flexible rules of evidence and procedure |

Strict procedural rules and adherence to the Evidence Act |

| Powers |

Limited to the scope defined by statute |

Has inherent powers, including judicial review |

| Appeal Process |

Decisions are usually subject to judicial review by higher courts |

Appeals lie to higher courts within the judicial hierarchy |

| Objective |

Provides speedy and specialized dispute resolution |

Ensures justice under general legal principles |

Need for Tribunals In India

- Addressing Case Pendency: Tribunals were established to tackle the backlog of cases in various courts.They also help in reducing delays in delivering justice.

- Reducing Court Workload: By handling specialized disputes, tribunals ease the burden on traditional courts. They allow the judiciary to focus on core legal matters.

- Faster and Efficient Decision-Making: Tribunals expedite dispute resolution compared to lengthy court procedures. Their processes are designed to be more streamlined and time-efficient.

- Expert-Driven Adjudication: Tribunals are staffed by legal professionals and subject-matter experts. This ensures informed and well-reasoned decisions in specialized areas.

- Speedy Resolution: Faster dispute resolution compared to conventional courts.

- Decentralization: Accessibility of justice across different regions.

- Specialised Role in Justice Delivery: They handle disputes in key areas such as:

- Environment: Environmental protection and regulatory issues.

- Armed Forces; Service-related grievances and military disputes.

- Taxation: Matters related to tax laws and compliance.

- Administrative Issues: Government policies, service matters, and regulatory decisions.

Salient Features of Tribunals in India

- Adherence to Natural Justice: Tribunals ensure fair hearings for all parties and prohibit self-judgment to uphold impartiality.

- Flexible Procedure: They are not bound by strict Civil Procedure Code (CPC) rules, allowing a more adaptable approach.

- Quasi-Judicial Authority: They can hear evidence, examine witnesses, and issue binding decisions like courts.

- Appellate Mechanism: Decisions can be appealed to higher authorities, including High Courts and the Supreme Court.

- Time-Bound Resolution: Tribunals expedite dispute resolution, reducing delays compared to traditional courts.

Landmark Cases on Tribunals in India

- S.P. Sampath Kumar vs Union of India (1987): Upheld the constitutional validity of the Administrative Tribunals Act, 1985. The judgement also affirmed judicial review as part of the basic structure but allowed tribunals to exercise it if they provided an effective mechanism.

- L. Chandra Kumar vs Union of India (1997): Judicial review by High Courts (Article 226) and Supreme Court (Article 32) cannot be excluded.

- Tribunals act as courts of first instance, but their decisions are subject to High Court review.

- Union of India vs R. Gandhi (2010): Tribunals performing judicial functions must have members with judicial expertise, akin to High Court judges.

- Reinforced judicial independence and decision-making quality in tribunals.

- Madras Bar Association v. Union of India (2021): Struck down the Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021, particularly provisions related to tribunal appointments and tenure.

- Reiterated that tribunals should maintain judicial independence and cannot be dominated by the executive.

|

Constitutional Provisions Relating To Tribunals

- The Original Constitution did not contain provisions with respect to tribunals.

- The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 added a new Part XIV-A to the Constitution. This part is titled ‘Tribunals’ and consists of only two Articles:

- Article 323A dealing with administrative tribunals

- The Parliament enacted the Administrative Tribunals Act in 1985, which empowers the Central government to establish the Central Administrative Tribunal and state-level administrative tribunals.

- Article 323B dealing with tribunals for other matters.

Key Differences Between Articles 323A and 323B

| Basis |

Article 323A |

Article 323B |

| Scope of Matters |

Establishes tribunals exclusively for public service matters. |

Covers tribunals for various other subjects like taxation, labor, and land reforms. |

| Authority to Establish |

Only Parliament can establish these tribunals. |

Both Parliament and State Legislatures can set up tribunals within their legislative domain. |

| Hierarchy of Tribunals |

Allows only a single tribunal for the Centre and each state, with no hierarchical structure. |

Permits the creation of multiple tiers of tribunals forming a hierarchy. |

Issues Faced By Tribunals in India

Classification of Tribunals in India

- Administrative Tribunals

- Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT): Handles service matters of central government employees, excluding defense personnel and Parliament staff.

- The President appoints members in consultation with the Chief Justice of India.

- State Administrative Tribunals (SATs): Established at the request of states to address service disputes of state government employees.

- The President appoints members after consulting the respective State Governor.

- Joint Administrative Tribunal (JAT): Formed for multiple states to adjudicate their administrative disputes.

- The President appoints members in consultation with the concerned State Governors.

- Other Tribunals

- National Green Tribunal (NGT): Established under the 2010 Act for environmental dispute resolution.

- Principal Bench in Delhi with regional benches in Bhopal, Pune, Kolkata, and Chennai.

- Foreigners Tribunals (FTs): Determine citizenship status under the Foreigners Act, 1946, primarily in Assam.

- Other states handle illegal foreigners through local courts before deportation/detention.

- National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT): Established under the Companies Act, 2013, to resolve corporate disputes and insolvency matters. Operational since 2016.

- Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT): Adjudicates disputes in the telecom sector to safeguard the interests of service providers and consumers.

|

- Conflict of Interest: The government, being a major litigant in tribunals, also controls the appointment and removal of tribunal members, raising concerns about impartiality.

- The executive decides the salary, tenure, and service conditions of tribunal members, affecting their autonomy and independence.

- Undermining the Judiciary:

- Tribunalization of Justice: Tribunals take over judicial functions, reducing the authority of regular courts and violating the separation of powers.

- Bypassing High Courts: Tribunals often bypass High Court jurisdiction, leading to legal challenges, though the Chandra Kumar case (1997) allowed appeals in High Courts.

- Structural and Administrative Challenges:

- Non-Uniform Appointment Process: Different tribunals have varied rules on member qualifications, retirement age, and infrastructure, affecting consistency and efficiency.

- Case Backlogs: Tribunals face significant delays, with the CAT alone having over 44,000 pending cases, as noted in the 272nd Law Commission Report.

- Persistent Vacancies: Recently, in January this year, the court directed Centre to furnish data on vacancies across all tribunals.

Way Forward

- Ensuring Independence of Tribunals: Tribunals must function independently and not be seen as an extension of the executive.

- Establishing a Separate Administrative Authority: The Supreme Court rulings (L Chandra Kumar (1997), R Gandhi (2010), Madras Bar Association (2014), Swiss Ribbons (2019)) mandate that tribunals should not function under the ministries they adjudicate against.

- Tribunals should be placed under the Ministry of Law and Justice instead of sectoral ministries.

- Easing Pressure on Constitutional Courts: High Courts should be the final court in most litigation after tribunal rulings, reducing unnecessary cases reaching the Supreme Court.

- “Special Leave to Appeal” to the Supreme Court should be limited to truly exceptional cases, ensuring judicial consistency and discipline.

Conclusion

A well-structured tribunal system will uphold justice while easing the burden on constitutional courts.

![]() 6 Mar 2025

6 Mar 2025