In a landmark judgment in Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir vs. Raja Muzaffar Bhat, the Supreme Court of India ruled that no environmental clearance for riverbed sand mining can be granted without a scientific replenishment study.

About Supreme Court Ruling on Sand Mining – Jammu & Kashmir Case

- Background of the Case: The case concerned sand extraction in Shaliganga Nallah, Jammu & Kashmir, linked to a National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) highway project.

- The National Green Tribunal (NGT) annulled the environmental clearance since the District Survey Report (DSR) lacked replenishment study data.

- Importance of Replenishment Studies: The Supreme Court held that replenishment studies are essential to determine sustainable extraction limits.

- These studies help prevent ecological damage, maintain groundwater recharge, and preserve river ecosystems.

- Analogy with Forest Conservation: The Court compared sand mining to forest management.

- Just as timber extraction requires assessment of natural regeneration, sand mining must also rely on scientific replenishment assessments before approvals.

- The Final Ruling: The Supreme Court dismissed appeals filed by the Jammu & Kashmir authorities and NHAI.

- It made replenishment studies mandatory in DSRs before granting mining clearances, reinforcing the principle of sustainable and scientific mining practices.

- Impact of the Judgment: The ruling sets a national precedent: no mining project can proceed without scientific validation of resource replenishment.

- It strengthens environmental governance, curbs hasty clearances, and aligns India’s policy with sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Importance and Need of Scientific Replenishment Study for Riverbed Sand Mining

- A “Replenishment Study” is a scientific assessment that measures the rate at which sand and other riverbed materials naturally regenerate in a river ecosystem.

- Purpose and Process of a Sand Replenishment Study: It involves monitoring the annual deposition of sand to determine how quickly it is replaced after extraction. This study helps establish sustainable extraction limits and ensures that the rate of mining does not exceed the river’s ability to replenish its sand reserves.

- Sustainable Resource Management: Replenishment studies ensure that sand extraction does not exceed the natural replenishment rate, preserving river ecosystems and preventing resource depletion.

- Ecological Balance: These studies help assess the impact of mining on riverbed stability, aquatic habitats, and biodiversity, reducing environmental degradation like erosion, flooding, and habitat loss.

- Informed Decision-Making: They provide scientific data for authorities to set sustainable extraction limits, guiding environmental clearance and avoiding overexploitation of riverbeds.

- Long-Term Viability: Without a replenishment study, mining can lead to irreversible ecological damage, affecting both the environment and the livelihoods of communities dependent on river resources.

- Legal Compliance: Replenishment studies align with regulations such as the Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines and EIA Notification (2016), ensuring mining activities meet environmental standards.

About Sand & Sand Mining

- Sand: Sand is an essential resource for construction, infrastructure, and manufacturing. It is used in concrete, bricks, glass, and other products.

- Sand Mining: Sand mining involves extracting sand from riverbeds, coastlines, and lakes. While crucial for development, excessive sand mining has serious ecological consequences.

- Policies and Regulations:

- Environment Protection Act (1986): Provides overarching safeguards for environmental protection.

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification (2016): Mandates District Survey Reports (DSRs) and replenishment studies for sustainable sand mining.

- Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines (2016): Focus on scientific management and monitoring of sand mining practices.

- Mines And Minerals (Development And Regulation) Act, 1957 (MMDR Act): Provides for the development and regulation of mines and minerals under the control of the Union.

- Defines Sand: A minor mineral under Section 3(e) of the MMDR Act and control of illegal mining comes under the legislative and administrative purview of the State Governments.

- Section 15 of the MMDR Act: It empowers the State Governments to make rules for regulating the grant of quarry leases, mining leases or other mineral concessions in respect of minor minerals and for purposes connected therewith.

- Section 23C of the MMDR Act: It empowers the State Governments to make rules for preventing illegal mining, transportation and storage of minerals and for the purposes connected therewith.

- Environmental Implications of Unrestricted Sand Mining: The Supreme Court in Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana (2012) highlighted that unchecked sand mining is ecologically unsustainable, leading to:

- Riverbank erosion and habitat destruction: Destabilisation of riverbanks, loss of riparian vegetation, and destruction of nesting/breeding sites.

- Depletion of groundwater tables: Excessive extraction deepens riverbeds, reduces groundwater recharge, and damages aquifers.

- Biodiversity loss: Fish breeding grounds and aquatic ecosystems get destroyed, threatening livelihood security of dependent communities.

- Heightened flood risks: Destabilised riverbeds weaken the river’s natural flood buffering capacity.

- Declining water quality: Higher turbidity, siltation, and pollution due to disturbed sediment balance.

- Long-term ecological imbalance: Altered river morphology leading to desertification risks in adjoining areas.

PWOnlyIAS Extra Edge:

About Illegal Sand Mining

- Definition: Illegal sand mining refers to unauthorized extraction of sand without proper licenses or in violation of environmental regulations.

- Supreme Court’s Definition of Illegal Mining (Common Cause v. Union of India): According to the Supreme Court, illegal mining includes:

- Mining operations carried out without holding a valid mining lease.

- Mining conducted in violation of the mining scheme, mining plan, or terms of the mining lease.

- Operations undertaken in contravention of environmental and forest laws, including:

- Environment (Protection) Act, 1986

- Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980

- Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974

- Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981

- Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972

- Impacts of Illegal Mining: Illegal mining leads to loss of biodiversity, river degradation, and social conflict over control of mining resources.

Reasons for Illegal Mining of Sand

- High Demand and Limited Legal Supply: Rapid urbanisation and infrastructure growth have sharply increased demand for sand. However, the legal supply is inadequate, pushing builders and contractors towards illegal channels.

- Corruption and Nexus: An unholy nexus between illegal miners, regulatory authorities, and law enforcement agencies often facilitates violations. For instance, the Goa Bench of the Bombay High Court noted that neither the Director General of Police (DGP) nor the Chief Secretary showed seriousness in curbing illegal sand mining.

- Poverty and Unemployment: In economically vulnerable regions, sand mining becomes a source of livelihood for the poor, despite its illegality.

- For example, in Bihar, workers extract the so-called “pila sona” (yellow gold) from the Son riverbanks, earning around ₹400 a day to support their families.

|

Consequences of Unchecked Sand Mining

- Ecological Challenges:

- Riverbank Erosion & Habitat Loss: Excessive extraction destabilizes riverbanks, damages aquatic ecosystems, and increases flood risks.

Biodiversity Decline: Rivers like the Chambal, Narmada, and Betwa face threats, especially species such as the gharial in the Chambal Sanctuary.

Biodiversity Decline: Rivers like the Chambal, Narmada, and Betwa face threats, especially species such as the gharial in the Chambal Sanctuary.- Slow Natural Replenishment: Millions of tonnes of sand are extracted annually, while natural replenishment is slow.

- Water Quality Degradation: Sedimentation elevates turbidity, harming aquatic life and compromising water quality.

- Economic Challenges:

- Revenue Loss: States lose substantial income due to unmonitored extraction; Telangana reported ₹172 crore in potential losses.

- Infrastructure Damage: Extraction near structural foundations weakens them, e.g., Mullarapatna Bridge collapse in Karnataka.

- Social and Security Challenges:

- Conflicts and Safety Risks: Monitoring and extraction can lead to confrontations and accidents; 124 fatalities were recorded between April 2022–Feb 2023.

- Threats to Enforcement: Officials monitoring sand operations faced attacks, highlighting enforcement challenges.

- Infrastructure of Smuggling: Discovery of secret extraction routes in Nagpur shows the scale of unregulated activity.

- Governance and Oversight Failures:

- Deficient District Survey Reports (DSRs): In Madhya Pradesh, nearly half of the districts lack valid or accessible DSRs—leading to unchecked mining and posing risks to community safety (e.g., the tragic death of a 13-year-old due to an unmarked mining pit).

- Audit Warnings: The Comptroller and Auditor General flagged unchecked extraction in Odisha’s Brahmani and Rushikulya rivers, estimating ₹51.69 crore in recoverable dues and pointing to state neglect in enforcement.

- High-Level Corruption: In Tamil Nadu, the Madras High Court has ordered a CBI investigation into a ₹5,832 crore unchecked beach sand mining scam, underlining systemic collusion among officials and political figures.

Government Initiatives for Sustainable Sand Mining

- Technological and Monitoring Measures:

- Permanent Check Posts in Bihar: Monitors sand transport and ensures regulatory compliance.

- Odisha’s Integrated Mining Management System (i3MS): Uses satellite imagery, GPS tracking, and drones for real-time monitoring.

- AI and Drone Surveillance (UP & Telangana, 2024): Tracks mining in sensitive river stretches.

- Policy and Regulatory Framework:

- Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines (SSMMG), 2016: Issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, these guidelines focus on:

- Identification of mining sources.

- Replenishment studies for riverbed materials (sand, gravel, boulders).

- District Survey Reports for planned extraction.

- Standard environmental safeguards for mining projects.

- Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining, 2020: Supplemental to SSMMG 2016, these guidelines strengthen regulation through:

- Identification and quantification of resources.

- End-to-end regulation of sand and gravel mining from source to final consumer.

- Use of IT-enabled services, drones, and remote sensing for surveillance at each stage.

- Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006: Makes environmental clearance mandatory even for small-scale sand mining projects, ensuring ecological safeguards.

- Sand Mining Framework (2018): Prepared by the Ministry of Mines, it incorporates best practices from states to promote sustainability, availability, affordability, and transparency in sand mining.

- Alternatives and Substitutes:

- Manufactured Sand (M-Sand): Promoted in Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka; incentives offered in 2024 reduce pressure on river ecosystems.

- Other Substitutes: Fly ash, crushed rock, artificial sand, copper slag reduce dependency on natural sand.

- Global Practices: China and USA produce crushed rock as an alternative material.

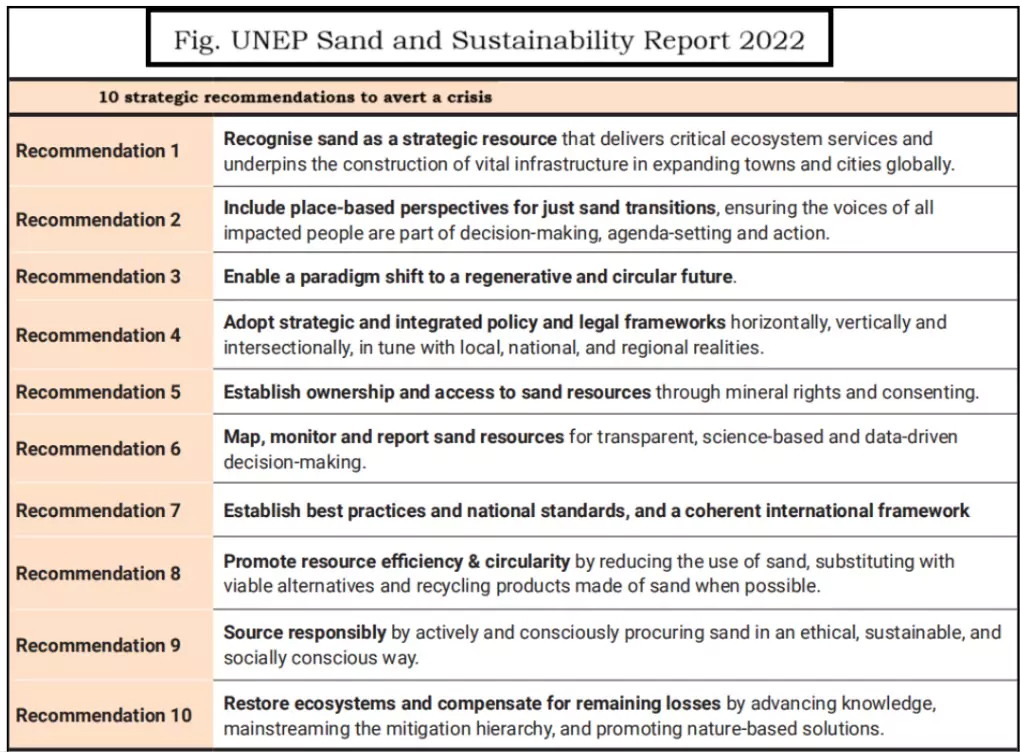

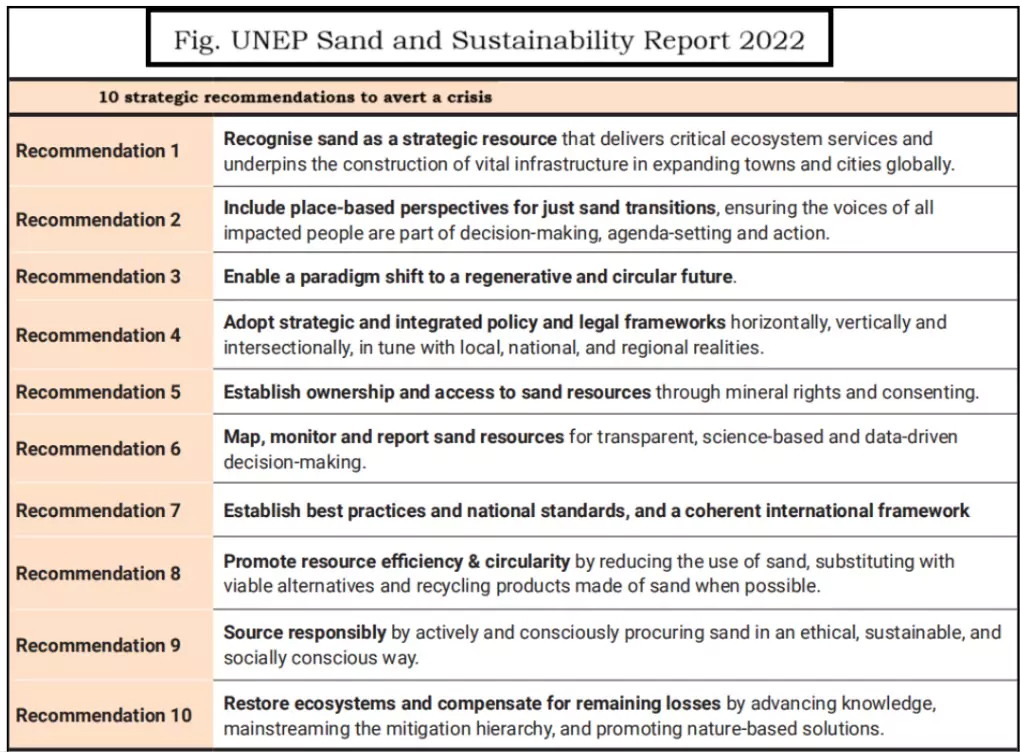

Global & International Framework Associated with Sand Mining

- UN Environment Programme (UNEP): UNEP advocates for sustainable mining practices and provides global frameworks for sand mining regulation.

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD): Article 7 urges countries to monitor the environmental impacts of sand mining and take preventive actions.

- UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): Articles 208 and 214 require countries to create laws that control pollution caused by sand mining, especially in marine environments.

Way Forward

- Promote Sustainable Alternatives: Reduce dependency on natural sand by encouraging manufactured sand (M-sand), artificial sand, fly ash, and crushed rock in construction.

- Avoid unnecessary consumption of natural sand in infrastructure projects, as recommended by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

- International Examples:

- Singapore: Copper slag used as a sand substitute in concrete.

- China and United States: Production of “crushed rock” as an alternative material.

- Incentivize industries to adopt eco-friendly materials, reducing environmental pressure on river ecosystems.

- Strengthen Regulatory Framework: Reclassify sand from a minor mineral to a major mineral, bringing it under central regulation for uniformity across states.

- Frame national guidelines for sand mining to ensure sustainable extraction and reduce illegal activities.

- Harmonize environmental and mining laws, integrating Supreme Court directions on replenishment studies, environmental clearances, and District Survey Reports.

Technological Interventions: Use satellite imagery, drones, GPS tracking, bar coding, and remote sensing for real-time monitoring of mining activities.

Technological Interventions: Use satellite imagery, drones, GPS tracking, bar coding, and remote sensing for real-time monitoring of mining activities.-

- Develop integrated mining management portals, like the Odisha system, enabling officials to regulate mining electronically.

- Track sand extraction, transport, and usage to ensure transparency and compliance with environmental norms.

- Enhance Enforcement and Penalties: Strictly enforce existing laws, making penalties stringent and deterrent-oriented.

- Conduct regular inspections, audits, and surprise checks in high-risk zones to prevent violations.

- Establish Basic Industry Standards: Develop standardized practices for sand mining to reduce unchecked/illegal operations.

- Scientists advocate for a global monitoring programme, creating benchmarks for sustainable mining, minimizing ecological damage, and legitimizing operations.

- Promote Public Awareness and Community Participation: Launch campaigns to educate citizens and stakeholders on the environmental and social impacts of sand mining.

- Encourage community-based monitoring, enabling local populations to report violations and safeguard river ecosystems.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling upholding replenishment studies for riverbed sand mining reflects India’s commitment to constitutional values of sustainable development, environmental justice, and the right to a healthy environment under Article 21, ensuring equitable and responsible resource management for future generations.

PWOnlyIAS Extra Edge

About National Green Tribunal (NGT)

- Establishment: Established in 2010 under the NGT 2010 for effective and expeditious disposal of environmental protection and conservation cases.

- Headquarters: Headquartered in Delhi with zonal benches in Bhopal, Pune, Kolkata, Chennai

Compositions

- Comprises a Chairperson, Judicial Members and Expert Members

- Chairperson: A retired Supreme Court judge or Chief Justice of a High Court

- Serves for five years or until age 70

- Appointed by the Central Government in consultation with the Chief Justice of India

- Members appointed for 5 year terms, not eligible for reappointment

- Judicial and Expert members appointed by Selection Committee

- Strength – minimum 10 members and maximum 20 members

Powers & Functions

- Set up for expeditious disposal of environmental cases

- Possesses appellate jurisdiction like a court of law

- Not bound by Code of Civil Procedure, follows principles of natural justice

- Mandated to dispose cases within 6 months of filing

|

Read More About: Illegal Sand Mining: Reasons, Challenges, And Regulation

![]() 25 Aug 2025

25 Aug 2025

Biodiversity Decline: Rivers like the Chambal, Narmada, and Betwa face threats, especially species such as the gharial in the Chambal Sanctuary.

Biodiversity Decline: Rivers like the Chambal, Narmada, and Betwa face threats, especially species such as the gharial in the Chambal Sanctuary. Technological Interventions: Use satellite imagery, drones, GPS tracking, bar coding, and remote sensing for real-time monitoring of mining activities.

Technological Interventions: Use satellite imagery, drones, GPS tracking, bar coding, and remote sensing for real-time monitoring of mining activities.