The Supreme Court recently indicated it would consider a plea to revive the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) and end the Collegium system.

- Recently, the Chief Justice of India (CJI) called for a National Judicial Policy to harmonise judicial functioning across jurisdictions.

Background of NJAC Revival Plea

- Challenge to the 2015 Verdict: The plea argues that striking down the NJAC and the 99th Constitutional Amendment substituted the democratic will of Parliament with judicial interpretation, disturbing the principle of Checks and Balances.

- Demand for Democratic Legitimacy: The petition stresses that the NJAC enjoyed near-unanimous parliamentary support and state ratification, carrying exceptional democratic legitimacy, which the 2015 verdict arguably curtailed.

- Collegium’s Opacity Highlighted: It asserts that the Collegium system lacks transparency, objective criteria, and public accountability, undermining institutional trust.

- Allegations of Nepotism: The plea argues the Collegium is vulnerable to nepotism, favouritism, and internal lobbying, weakening meritocratic credibility.

- Separation of Powers Issue: It frames NJAC as an effort to restore a balanced interpretation of Separation of Powers, where the Executive and Legislature have a constitutionally valid role in appointments.

- Constitutional Intent Misinterpreted: The petition contends that the framers never intended a judge-controlled appointments model, having rejected judicial “concurrence” during drafting.

- Demand for Void Ab Initio Declaration: The plea seeks to declare the 2015 judgment null from inception, reinstating the NJAC as the rightful mechanism.

- Symbolic Mention on Constitution Day: Raised on Constitution Day, the plea highlights concerns about constitutional accountability and democratic oversight.

CJI’s Call for a National Judicial Policy- A Framework for Coherence:

- National Judicial Policy would act as a common guiding framework for all courts to follow uniform standards.

- Aim: To move beyond mere administrative management to ensuring genuine institutional equity in justice delivery.

- Need for a National Judicial Policy: The policy addresses deep-rooted issues undermining the rule of law and equality.

- Need for Interpretational Coherence: Inconsistent rulings across India’s 25 High Courts lead to avoidable divergence in legal interpretation.

- The CJI stressed that this heterogeneity fundamentally threatens Equality before Law and Certainty of Law.

- The “Judicial Symphony” Vision: The policy aims for courts to operate like a unified “judicial symphony”—many voices guided by a common constitutional rhythm, thus strengthening the judiciary’s institutional identity.

- Addressing the Rights vs. Remedies Gap: The policy is crucial for achieving Access to Justice (linked to Articles 32 (Right to Constitutional Remedies) and 39A (Equal Justice and Free Legal Aid)).

- The CJI noted that systemic barriers like cost, language, and delay create unequal access, making justice elusive for the marginalized and turning it into a privilege of wealth or geography.

- Institutional Equity: By minimizing disparities in procedural and legal application, the policy ensures that the quality of justice does not depend on location.

|

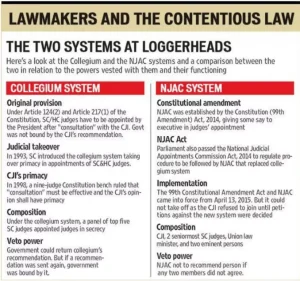

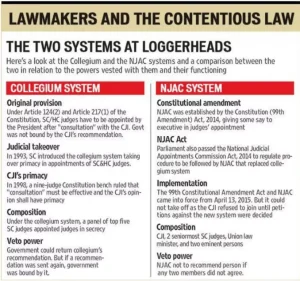

About National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC)

NJAC was introduced by the 99th Constitutional Amendment Act, 2014 to regulate the appointment of judges and empower the commission.

- Feature: The NJAC consisted of the Chief Justice of India (as Chairman), two senior most judges of the Supreme Court, the Law and Justice Minister and two eminent persons.

- Struck Down: The Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court declared NJAC unconstitutional citing that it violates the basic structure of the Constitution of India.

- The Court determined that the NJAC may jeopardise impartiality and objectivity in the appointment process, thus endangering judicial independence.

Appointment of Judges in India

Through the collegium system, judges are appointed and transferred in the Supreme Court and high courts across the country.

- Constitutional Provisions:

- Article 124: The appointment of Supreme Court judges should be made by the President after consultation with such judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court as the President may deem necessary.

- Article 217: The appointment of High Court judges should be made by the President after consultation with the CJI and the Governor of the state.

- Procedure of Appointment:

- Supreme Court Judges:

- Recommendations by Collegium: All appointments must be recommended by the collegium.

- Government Approval: This recommendation is then sent to the Central government via the law minister and then the prime minister before the President’s approval.

- High Court Judges:

- Recommendations of Collegium: High Court collegium must send a recommendation to the Chief Minister (CM) and the governor of the state.

- Recommendations of State Executive: The governor will then send the recommendation to the Union Minister of Law and Justice, who will forward the recommendation to the CJI.

- Government’s Approval: The CJI, after being informed by the two senior-most judges of the SC, should send the recommendation to the Union Minister of Law and Justice.

- He/she then puts the recommendations before the Prime Minister who will advise the President about the appointment.

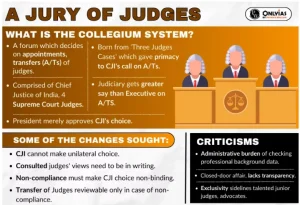

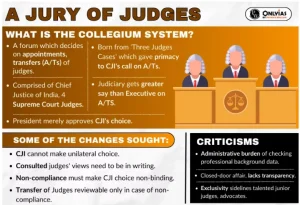

About Collegium System

The Supreme Court held that the collegium system protects the independence of the judiciary.

- The Supreme Court Collegium: The collegium system is a forum including the Chief Justice of India and four senior-most judges of the SC, which recommends appointments and transfers of judges.

High Court Collegium: It includes the Chief Justice of the High Court along with its two senior-most judges

High Court Collegium: It includes the Chief Justice of the High Court along with its two senior-most judges

- These appointments include elevation of high court judges to the apex court and direct appointments of senior advocates as apex court judges.

- Judges of the higher judiciary are appointed only through the collegium system, and the government has a role only after names have been decided by the collegium.

- Evolution of Collegium:

- First Judges Case (1981): Supported executive primacy by holding that consultation does not mean concurrence.

Second Judges Case (1993): Shifted to judicial primacy, establishing the Collegium.

Second Judges Case (1993): Shifted to judicial primacy, establishing the Collegium.- Third Judges Case (1998): Expanded the Collegium to include the CJI & four senior judges, institutionalising judge-controlled appointments.

- Significance:

- A Structured Method: For the appointment and transfer of judges in higher courts.

- Preservation of the Independence: Independence of judiciary from the executive branch by endowing judges with substantial influence in the appointment of judges.

- Drawback: The collegium system has frequently been criticised for its lack of accountability and transparency, and the prevalence of nepotism.

- In the collegium system, no one knows what the criteria are to select judges. The system offers room for favouritism, which could prevent competent and deserving judges from being appointed.

- Can the Collegium system be replaced?

- Replacing the Collegium system calls for a Constitutional Amendment Bill.

- It requires a majority of not less than two-thirds of Members of Parliament present and voting in Lok Sabha as well as Rajya Sabha.

- It also needs the ratification of legislatures of not less than one-half of the states.

Need for NJAC over Collegium System

The NJAC was an elegant reform. Various experts, including former judges, have argued that the NJAC is a better system. Also, since the world over, the judiciary is not the sole body which appoints judges.

- Faster Appointment: If appointments of judges have to take place faster, there is a need to bring back the NJAC. It could have resulted in faster nominations of judges because of its democratic structure.

- An Efficient Method: The NJAC could provide a more efficient method of appointing judges, encouraging communication between the arms of the state, and addressing some of the perceived drawbacks of the collegium system.

- Inclusiveness: The NJAC Act, 2014 (99th Constitutional Amendment, 2014) sought to give politicians and civil society a final say in the appointment of judges to the highest courts.

- Independence of the Judiciary: Parliament in its wisdom enacted the NJAC Act and in order to give credence to the NJAC, it was to be headed by the Chief Justice of India, and include the Law Minister, two eminent persons, and two senior judges.

Challenges to Judicial Reforms in India

- Constitutional and Ideological Barriers:

- Basic Structure Limits: Reforms like the NJAC face the Basic Structure doctrine, which protects Judicial Independence and Judicial Primacy in Appointments, making major legislative changes vulnerable to being struck down.

- Federal Autonomy vs. National Policy: High Courts’ powers under Articles 226/227 and diverse state legal cultures make it difficult to implement a centralised judicial policy without undermining their constitutional autonomy.

- Institutional and Political Friction:

- Executive–Judiciary Trust Gap: Long-standing mistrust causes clashes over the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP), delays in appointments/transfers, and inadequate infrastructure funding, slowing meaningful reform.

- Internal Resistance: Sections of the judiciary and Bar resist altering familiar systems (like the Collegium or traditional procedures), hindering structural and technological changes.

- Financial and Capacity Constraints:

- Underfunding & Weak Infrastructure: Low judicial budgets lead to poor court infrastructure, outdated technology, and limited support staff, hampering reforms such as e-Courts or uniform policies.

- Vacancies & Heavy Workload: High vacancies and rising pendency push courts into crisis management, leaving little room for long-term reform planning.

- Societal and Access Barriers:

- Language and Diversity Gaps: Non-uniform court languages and slow adoption of AI-based translation restrict access for citizens and limit diverse representation in the higher judiciary.

- Lack of Data & Clear Criteria: The absence of a robust national judicial data grid and non-transparent Collegium criteria weaken evidence-based policymaking and fuel concerns about accountability.

Lessons from Other Countries:

- UK: The independent Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) oversees the process of judges appointments.

- The JAC consists of 15 members; from which 12 members are selected through a process of open competition.

- France: The judges are appointed for three-year terms, which are renewable on the recommendation of the Ministry of Justice.

- South Africa: There is a 23-member Judicial Services Commission (JSC) that advises the President to nominate the judges.

- US: Judges of the Federal Court are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate.

|

Way Forward

- Reform Judicial Appointments Through a Hybrid Model:

- Inclusive Composition: NJAC proposed a plural body with the Chief Justice of India (CJI), two senior judges, Law Minister, and two eminent persons, broadening representation.

- Veto for Checks: A two-member veto acted as an institutional safeguard to prevent dominance and ensure balanced decision-making.

- Democratic Inclusion: By restoring a role for the Executive and Legislature, NJAC aimed to enhance transparency, accountability, and democratic legitimacy in appointments.

- Establish a Transparent and Objective Selection Framework: Define clear criteria, qualifications, and procedures for appointments; ensure reasoned decisions, merit-based evaluation, performance indicators, and transparency in transfers and elevations.

- Strengthen Public Participation and Diversity: Introduce public consultations, open hearings, or a multi-stakeholder appointments commission including eminent citizens to bring in diverse perspectives and enhance social legitimacy.

- Accelerate Digital and Language Access Reforms: Expand AI translation tools, multilingual platforms, and digital filing systems to reduce barriers of language, geography, and cost, advancing institutional equity across courts.

- Promote Mediation, ADR, and a National Judicial Policy: Strengthen mediation and ODR to reduce pendency, and implement a National Judicial Policy to harmonise procedures while respecting federal autonomy and constitutional balance.

- Adopt Alternate Proposal: The government has suggested a three-step process of appointments based on justice Madan B. Lokur’s ruling by involving:

- appointment by way of applications or nominations

- committee of eminent citizens

- submission of a written file to the executive

Appointments based on Justice Madan B. Lokur’s Ruling:

- Appointment by way of Applications or Nominations: Nominations should be made not just by the collegium, but also other judges of the court, the Prime Minister, President and the Attorney General.

- Committee of Eminent Citizens: A participatory appointment process is needed which must seek inputs from a committee of eminent citizens, which would not be restricted to the legal fraternity.

- Submission of Written file to the Executive: The entire file with all views recorded in writing must be sent to the executive for its views on the antecedents, character, integrity and relevant facets” to determine if the candidate was suitable for the post of a senior judge.

|

Conclusion

India stands at a transformative moment in judicial reform. Debates on NJAC revival and the National Judicial Policy aim for constitutional equilibrium—balancing judicial independence, democratic legitimacy, federal diversity, and accountability. Justice delivery must ensure transparency, coherence, and equitable access for all citizens.

![]() 27 Nov 2025

27 Nov 2025

High Court Collegium: It includes the Chief Justice of the High Court along with its two senior-most judges

High Court Collegium: It includes the Chief Justice of the High Court along with its two senior-most judges

Second Judges Case (1993): Shifted to judicial primacy, establishing the Collegium.

Second Judges Case (1993): Shifted to judicial primacy, establishing the Collegium.