Recently, the Supreme Court of India denied bail to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam in the 2020 Delhi riots conspiracy case under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), while granting bail to five co-accused, reinforcing strict statutory bail standards.

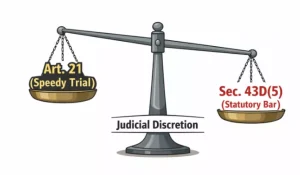

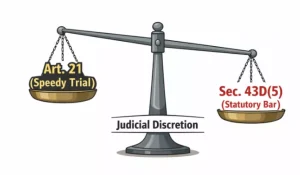

- The judgment reflects a paradigm shift towards a Security-Centric Jurisprudence, where the Court acts as a mediator between Executive Necessity and the Sanctity of Individual Liberty under Article 21.

Key Highlights of the Supreme Court Judgment

- Application of the Doctrine of Proportionality: By distinguishing between ‘intellectual architects’ and ‘subsidiary facilitators,’ the Court applied the Doctrine of Proportionality, ensuring that the severity of judicial restraint on liberty is commensurate with the perceived threat to the State’s integrity.

Differential Treatment of Accused: The Court held that criminal law does not mandate identical outcomes for all accused arising from a common transaction; bail must be decided based on the individual role attributed to each accused.

Differential Treatment of Accused: The Court held that criminal law does not mandate identical outcomes for all accused arising from a common transaction; bail must be decided based on the individual role attributed to each accused.- Judicial Recognition of a Hierarchy of Offenders: The judgment formally recognises a hierarchy of culpability among accused persons, even when they are charged under identical statutory provisions.

- By distinguishing between principal conspirators and subsidiary facilitators, the Court affirmed that equal charges do not mandate equal bail outcomes, reinforcing role-based judicial assessment under stringent national security laws.

- Qualitatively Different Footing: Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam were found to have central and formative roles in the alleged conspiracy, placing them on a distinct legal footing from other accused.

- Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act Bail Threshold: Prolonged incarceration alone cannot justify bail under Section 43D(5) of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, which imposes stringent statutory restrictions.

- Prima Facie Evaluation: Courts must first assess the gravity of the offence, the statutory framework, and the prima facie evidentiary value of the prosecution’s case before considering bail.

- National Security Consideration: In offences affecting the sovereignty, integrity, or security of the State, courts are required to exercise greater judicial restraint at the bail stage.

- Bail to Co-accused: Bail was granted to five co-accused after noting the subsidiary nature of allegations, subject to stringent conditions to safeguard the trial process.

Background of the Case

- 2020 Delhi Riots: In February 2020, communal violence in North-East Delhi resulted in 53 deaths, hundreds of injuries, and large-scale damage to public and private property.

- Nature of Allegations: The accused are alleged to have been part of a coordinated larger conspiracy to incite violence, charged under the UAPA and other penal provisions.

- Key Accused: Former Jawaharlal Nehru University student Umar Khalid and activist Sharjeel Imam were alleged to have played ideological and organisational roles in the conspiracy.

- High Court Proceedings: The Delhi High Court denied bail to nine accused in September 2023, describing Khalid and Imam as the “intellectual architects” of the violence.

- Defence Arguments: The accused contended that their actions fell within the constitutional right to protest under Article 19 of the Constitution of India, and that prolonged incarceration amounts to punishment without trial.

Legal Framework and Judicial Precedents

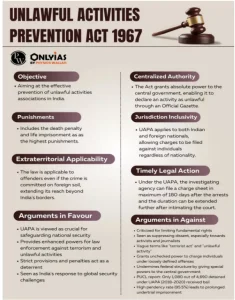

- Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA): A special national security legislation enacted to prevent activities threatening the sovereignty, integrity, and security of India.

- Section 43D(5) lays down a stringent bail regime, permitting denial of bail if the court finds the prosecution case to be prima facie true.

Interpretation of “Terrorist Act” under Section 15 of the (UAPA)

- Definition: Section 15 of the UAPA defines a “terrorist act” as any act committed with the intent to threaten the unity, integrity, security, economic security, or sovereignty of India, or to strike terror in the people.

- Judicial Expansion of “Means”: The Supreme Court adopted an expansive interpretation of the phrase “by any other means of whatever nature”, holding that terrorism is not determined solely by the instrumentality employed, but by the design, intent, and effect of the act.

- Non-Conventional Acts as Terrorism: This interpretation allows even non-conventional methods, such as organised disruption or mass mobilisation, to fall within the ambit of terrorism if they are alleged to threaten national security.

|

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC): Provides the general procedural framework for arrest, investigation, and bail.

- In cases involving special statutes like UAPA, special law prevails over general law.

- Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC): Invoked for offences such as criminal conspiracy, rioting, unlawful assembly, and promoting enmity between groups, often read with UAPA provisions.

- Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS): Replaces the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC); BNS Section 113 now explicitly defines “Terrorist Acts,” mirroring UAPA to target acts threatening sovereignty, unity, and integrity.

- Constitution Provisions of India:

- Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty): Liberty may be curtailed only through procedure established by law, including valid statutory restrictions.

- Article 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(b): Guarantees freedom of speech and peaceful assembly, subject to reasonable restrictions in the interests of public order and security of the State.

- Strengthening Jurisprudence: The ruling signifies a move from Procedural Due Process to a stricter Statutory Embargo, where the gravity of the ‘design and intent’ of an act outweighs the traditional ‘Bail is the Rule’ norm.

- Judicial Precedents Governing Bail under UAPA:

- National Investigation Agency v. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali (2019): The Supreme Court held that at the bail stage under UAPA, courts must rely on the prosecution’s version at face value and should not conduct a detailed examination of evidence.

- Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab (1994): Upheld the validity of stringent anti-terror laws while stressing the need for judicial caution to prevent misuse.

- Union of India v. K.A. Najeeb (2021): Recognised that prolonged incarceration and delay in trial can justify bail in exceptional circumstances, though such relief remains narrow and case-specific.

- Application in the Present Case: The Supreme Court relied on Watali to reaffirm statutory restraint on bail and distinguished Najeeb, holding that delay alone cannot override UAPA restrictions when the alleged offence impacts national security.

Impact of the Recent Supreme Court Judgment

- Impact on Bail Jurisprudence: Reinforces the stringent bail framework under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA).

- Clarifies that prolonged incarceration alone is insufficient to grant bail in national security cases, narrowing the scope of relief under Article 21 at the bail stage.

- Precedential Impact on UAPA Cases: Strengthens reliance on National Investigation Agency v. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali (2019), reaffirming that courts must accept the prosecution’s version at face value while considering bail.

- Limits expansive application of Union of India v. K.A. Najeeb (2021) by treating delay-based bail as an exception, not the norm.

- Impact on the Right to Dissent and Protest: The judgment raises concerns regarding the potential criminalisation of dissent, particularly where speech, mobilisation, and ideological expression are construed as elements of a broader conspiracy.

- The elevated bail threshold under the UAPA may produce a chilling effect on student movements, civil society activism, and political mobilisation, thereby narrowing the practical space for democratic protest.

- The ‘Chilling Effect’ and Substantive Due Process: The reliance on a prima facie standard, wherein the prosecution’s narrative is accepted at face value without rigorous evidentiary scrutiny at the bail stage, raises serious concerns for Substantive Due Process.

- In prolonged trials, such an approach risks transforming pre-trial detention into de facto punishment, undermining the constitutional guarantee of personal liberty under Article 21.

- Narrowing the Constitutional Space for Protest: The Supreme Court rejected the argument that only overtly violent acts fall within the definition of terrorism, holding that even non-violent methods such as road blockades or “chakka jams” may attract UAPA provisions if they form part of an alleged larger conspiratorial design.

- This interpretation blurs the line between legitimate democratic protest and criminal conspiracy, raising concerns regarding the future contours of constitutionally protected dissent.

- Impact on Trial and Due Process: Increases the risk of prolonged pre-trial incarceration, especially in complex conspiracy cases involving large volumes of evidence and multiple witnesses.

- Shifts emphasis from “bail as the rule” to “incarceration as the norm” under special security laws.

- Systemic Delay in Criminal Justice Delivery: The case has emerged as emblematic of broader systemic delays in India’s criminal justice system, where prolonged pre-trial incarceration increasingly substitutes for timely adjudication.

- In complex UAPA cases involving multiple accused, voluminous evidence, and lengthy investigations, the duration of the process itself risks becoming punitive.

- Impact on Judicial Discretion: Constrains judicial discretion at the bail stage, prioritising statutory mandates over equitable considerations.

- Encourages role-based differentiation, ensuring individual culpability is assessed separately rather than adopting a blanket approach.

- Impact on National Security Governance: Signals strong judicial backing for the State’s counter-terror and internal security framework.

- Enhances the deterrent value of UAPA, but simultaneously underscores the need for institutional safeguards against misuse.

About Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA)

- Enactment and Purpose: The UAPA was passed in 1967, following recommendations from the Committee on National Integration and Regionalism appointed by the National Integration Council.

- It was enacted to prevent unlawful activities that threaten the sovereignty and integrity of India.

Constitutional Basis: The Constitution (Sixteenth Amendment) Act, 1963 amended Article 19(2), allowing Parliament to impose reasonable restrictions on: Constitutional Basis: The Constitution (Sixteenth Amendment) Act, 1963 amended Article 19(2), allowing Parliament to impose reasonable restrictions on:-

- Freedom of speech and expression

- The right to assemble peacefully

- The right to form associations or unions

- Unlawful Activity: Defined as any action intended to disrupt India’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

- Scope: The UAPA applies to both Indian and foreign nationals and is enforceable throughout India.

- Forfeiture of Proceeds: Under Section 24A, proceeds derived from terrorism can be forfeited to the Central or State Government, regardless of whether the individual has been convicted.

- Exemptions: Individuals who were members of a now-banned organization before its designation as a terrorist group, and who did not engage in its activities afterward, are exempted from provisions of the UAPA.

Amendments to the UAPA

- 2004 Amendment:

- Introduced the term “terrorist act” and allowed the banning of organisations involved in terrorist activities.

- As a result, 34 organisations, including Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, were banned.

- 2019 Amendment:

- Empowered the Central Government to designate individuals as terrorists based on specific criteria.

- Granted the Director-General of the National Investigation Agency (NIA) authority to approve the seizure or attachment of property related to ongoing investigations.

- Allowed NIA officers of Inspector rank or above to investigate terrorism-related cases.

|

| Critical Analysis of the Supreme Court Judgment |

| Arguments Supporting the Verdict |

Arguments Against the Verdict |

- Protection of National Security: The judgment prioritises the sovereignty, integrity, and security of India.

- It is recognising that offences under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA) require a higher threshold for bail than ordinary criminal cases.

|

- Prolonged Incarceration Without Trial: Continued detention for several years risks violating the spirit of Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty).

- This is effectively amounting to punishment without conviction.

|

- Legislative Intent Respected: By strictly applying Section 43D(5) of UAPA, the Court upheld Parliament’s intent to impose statutory restraints on bail in terror and conspiracy-related offences.

|

- Erosion of “Bail as the Rule” Principle: The judgment further weakens the long-standing criminal law norm that bail, not jail, is the rule, especially concerning undertrials.

|

- Role-based Judicial Assessment: The ruling reinforces individualised culpability, ensuring that accused with central and formative roles are treated differently from those with subsidiary involvement.

- It is strengthening the credibility of conspiracy prosecutions.

|

- Low Evidentiary Threshold at Bail Stage: Reliance on a prima facie standard under UAPA allows denial of bail without rigorous testing of evidence.

- It is raising concerns of over-criminalisation of speech and association.

|

- Consistency with Judicial Precedents: The decision aligns with National Investigation Agency v. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali (2019).

- It is preserving doctrinal consistency in UAPA bail jurisprudence.

|

- Chilling Effect on Dissent: The verdict may discourage peaceful protest, student activism, and political expression.

- This is blurring the line between constitutional dissent and criminal conspiracy.

|

- Deterrence Against Organised Violence: A strict bail approach may deter organised and ideologically driven violence, signalling that planning and incitement are treated as seriously as physical participation.

|

- Risk of Executive Overreach: Strong deference to the prosecution at the bail stage increases the possibility of misuse of anti-terror laws for prolonged detention rather than expeditious justice.

|

Challenges and Concerns Arising from the Supreme Court Judgment

- Prolonged Pre-trial Incarceration: Under UAPA, accused like Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam can remain in custody for years before trial concludes.

- Raises concerns over violation of Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty) and punishment without conviction.

- Chilling Effect on Dissent and Protest: High bail thresholds for alleged conspiracies may discourage peaceful protests, activism, and student movements.

- Risks criminalising speech and assembly, potentially impacting freedom under Articles 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(b).

- Limited Judicial Discretion at Bail Stage: Strict statutory provisions in UAPA limit courts’ equitable discretion, prioritising statutory mandates over individual circumstances.

- It may lead to perceived rigidity and reduced flexibility in justice delivery.

- Determination of What Constitutes a “Terrorist Act”: The ruling reinforces prosecutorial and judicial primacy in determining whether an act qualifies as terrorism at the bail stage.

- Limited evidentiary scrutiny under the prima facie standard raises concerns about early-stage classification of conduct as a terrorist act, particularly in cases involving political protest or mass mobilisation.

- Risk of Misuse of Anti-Terror Laws: Strong deference to prosecution’s version at the prima facie stage can be exploited for prolonged detention, particularly in politically sensitive or controversial cases.

- Trial Delays and Overloaded Justice System: Complex cases with multiple accused, voluminous evidence, and numerous witnesses can face years-long trials, exacerbating challenges of speedy justice.

- Balancing National Security with Civil Liberties: Ensuring sovereignty and security without compromising constitutional rights remains a persistent challenge.

- Courts must continually navigate the tension between security imperatives and democratic freedoms.

Way Forward

- Time-bound Trials: UAPA cases often involve multiple accused, voluminous evidence, and complex investigations.

-

- Fast-track or time-bound trials can prevent prolonged pre-trial incarceration and ensure speedy justice, safeguarding Article 21 rights.

- Establishing a ‘Mathematical Threshold’ for Delay: To prevent the ‘Process from becoming the Punishment,’ the judiciary must establish a clear Time-bound Cut-off. If a trial fails to commence within a reasonable timeframe (e.g., 2 years), the Constitutional Right to a Speedy Trial must eventually supersede the statutory restrictions of the UAPA.

- Clear Judicial Guidelines for Bail: Courts should develop standardised criteria for assessing bail in national security and conspiracy cases, balancing statutory restraint with individual liberty.

- Role-based differentiation must continue, but reasonable conditions should also facilitate conditional bail where appropriate.

- Legislative Oversight and Safeguards: Parliament should periodically review UAPA provisions to prevent misuse while maintaining national security objectives.

- Introduction of mechanisms for interim judicial review of prolonged detentions could strengthen checks and balances.

- Protecting Democratic Freedoms: Ensure that peaceful protest, dissent, and student activism are not inadvertently criminalised under broad interpretations of conspiracy or incitement.

- Sensitisation of law enforcement agencies and judiciary regarding constitutional freedoms can prevent overreach.

- Strengthening Trial Infrastructure: Invest in digital case management, witness protection, and forensic capabilities to speed up complex investigations.

- Reduces delays that often prolong pre-trial detention and improves quality of justice.

- Balanced Approach to Security and Liberty: A nuanced approach is required to maintain national security, while protecting civil liberties, constitutional rights, and the rule of law.

- Encourages judicial innovation and proportionate application of law, ensuring that exceptional laws remain exceptional.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court ruling underscores the need to balance national security with civil liberties, reinforcing UAPA bail restrictions while highlighting challenges of prolonged detention, limited judicial discretion, and protection of peaceful dissent in a democratic framework.

- Ultimately, the survival of a vibrant democracy depends on the judiciary’s ability to distinguish between the Critic and the Conspirator. The UAPA must remain a shield for the Republic, not a shackle for legitimate democratic aspirations.

![]() 6 Jan 2026

6 Jan 2026

Differential Treatment of Accused: The Court held that criminal law does not mandate identical outcomes for all accused arising from a common transaction; bail must be decided based on the individual role attributed to each accused.

Differential Treatment of Accused: The Court held that criminal law does not mandate identical outcomes for all accused arising from a common transaction; bail must be decided based on the individual role attributed to each accused.