Even as India targets 500 GW renewable capacity by 2030, the real gap lies in quality of access—reliable power and gender inclusion in rural areas. The shift must move from mere connections to women-led Decentralised Renewable Energy (DRE).

- Women-led DRE can transform rural women from energy consumers to energy entrepreneurs and decision-makers.

About Women-Led Decentralized Renewable Energy (DRE)

- Refers: DRE refers to a transformative ownership model where small-scale energy systems—such as solar mini-grids, solar-powered water pumps, and solar dryers—are managed and owned by women’s collectives, notably Self-Help Groups (SHGs).

- The Model: Unlike centralized mega-parks, DRE systems are installed near the point of use.

- This model positions women as the primary designers, owners, and operators, ensuring the infrastructure serves both domestic dignity and economic productivity.

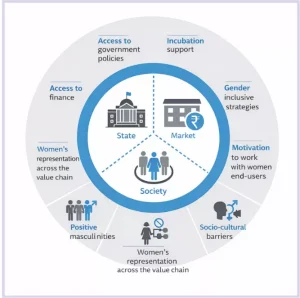

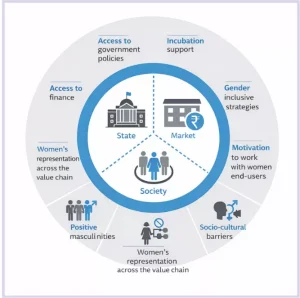

- The Framework: It operates through the “Samaj-Sarkar-Bazar” (Society-Government-Market) triad, where community trust (Samaj) is supported by government policy (Sarkar) and private sector efficiency (Bazar).

About Distributed Renewable Energy (DRE)

- DRE is the decentralized alternative to the traditional “big power plant” model. Instead of relying on a massive central grid, it generates power exactly where it is needed.

Six core pillars of the DRE model

- Localized Power Generation: Unlike the conventional grid that transmits electricity over hundreds of kilometers, DRE systems are site-specific.

- They use locally available resources—like sunlight, wind, or agricultural waste—to power a single home, a school, or a small cluster of shops.

- This eliminates the transmission and distribution (T&D) losses that plague long-distance power lines.

- Modular and Scalable Design: DRE is not a “one size fits all” solution.

- It is highly flexible; a village can start with a small solar lantern or a single rooftop panel and eventually expand into a micro-grid that powers entire irrigation pumps or small-scale industries.

- This allows for incremental investment as a community’s energy needs grow.

- Energy Security and Resilience: As DRE operates independently of the national grid, it is less vulnerable to large-scale blackouts or “load shedding.”

- In disaster-prone or remote areas (like forests or mountains), DRE acts as a reliable backup, ensuring that critical services like vaccine refrigeration and emergency lighting stay functional even if the main grid fails.

- Catalyst for “Productive Use” (PURE): DRE goes beyond basic lighting. Its true value lies in Productive Use of Renewable Energy (PURE).

- By powering machinery like flour mills, silk reeling machines, or solar dryers, DRE transforms a rural household from a consumer of electricity into a productive economic unit, directly increasing local incomes.

- Democratized Ownership: Traditional energy is often controlled by large corporations or the state. DRE shifts the power (literally) to the community.

- It allows for Women-Led models where local Self-Help Groups (SHGs) or cooperatives own and manage the energy assets, ensuring that the revenue stays within the local economy rather than flowing back to a central utility.

- Environmental and Health Benefits: DRE is a clean-tech solution that replaces diesel generators and kerosene lamps. This leads to a massive reduction in Indoor Air Pollution (IAP), which is a leading cause of respiratory issues among rural women and children.

- By skipping the “fossil fuel phase,” DRE helps developing regions leapfrog directly to a sustainable, low-carbon future.

|

The Current Landscape- Beyond the Power Grid

While the Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana (Saubhagya) brought physical wiring to nearly every household, “quality of supply” remains a bottleneck.

- The Reliability Deficit: Intermittent power and voltage fluctuations in rural areas lead to “paper electrification,” where clinics cannot refrigerate life-saving vaccines and schools lack reliable digital tools.

- Energy Inequality: There is a stark disparity between lighting a bulb and powering a kitchen; millions of women still rely on hazardous biomass for cooking because the central grid often fails to meet their thermal energy needs.

| Comparative Analysis- Energy Models for Rural India |

| Feature |

Centralized Grid Model |

Women-Led Decentralized Renewable Energy (DRE) |

| Primary Goal |

- Bulk Generation & National Security: Focused on meeting industrial and urban demand through large-scale power plants.

|

- Localized Empowerment: Focused on providing reliable power for rural livelihoods and domestic dignity.

|

| Management & Governance |

- Top-Down: Managed by state Distribution Companies (DISCOMs) or large corporations; decisions are made far from the end-user.

|

- Bottom-Up: Managed by Self-Help Groups (SHGs) or village collectives; governance is community-driven and responsive.

|

| Reliability of Supply |

- Intermittent: High susceptibility to Transmission and Distribution (T&D) losses, voltage fluctuations, and frequent load-shedding.

|

- High Reliability: Generation occurs at the point of use, ensuring stable, 24/7 power for critical services and equipment.

|

| Gender Role |

- Passive Consumer: Women are viewed as “beneficiaries” with no agency over energy infrastructure or pricing.

|

- Active Owner: Women are the legal owners, operators, and decision-makers, controlling the “switch” of their local economy.

|

| Economic Impact |

- Standardization: Focuses on lighting bulbs (illumination) rather than powering productivity (milling, chilling, sewing).

|

- Productive Use (PURE): Specifically designed to automate labor-intensive tasks, boosting household income and local entrepreneurship.

|

| Technical Maintenance |

- Urban-Centric: Relies on male technicians from cities; results in long “downtime” when rural systems break down.

|

- Localized Skillset: Creates a cadre of “Oorja Sakhis” or “Solar Didis”—local women trained in STEM to handle repairs immediately.

|

| Capital Structure |

- Public/Corporate Debt: Requires massive, high-interest capital for large-scale infrastructure like transmission lines.

|

- Micro-Finance & Green Credit: Utilizes SHG savings and dedicated “Green Credits” to create community-owned assets.

|

| Social Outcome |

- Service Delivery: Measures success by the number of connections (wires) reached.

|

- Sovereignty: Measures success by the increase in female agency, safety, and economic independence.

|

Why the Need for Women-Led DRE?

Energy poverty is a gendered burden, and localized renewable solutions address several critical dimensions:

- Health and Nutrition: Replacing biomass “chulhas” with clean energy can prevent approximately 200,000 premature deaths annually caused by indoor air pollution.

- Mitigating Time Poverty: Women in rural India spend an average of 3–4 hours daily gathering fuelwood. DRE-driven automation reclaims this time for education, entrepreneurship, or rest.

- Safety and Agency: Reliable solar street lighting in states like Uttar Pradesh has directly increased female attendance in evening community meetings and markets, enhancing their participation in local governance.

- Productive Use of Renewable Energy (PURE): DRE enables rural women-led enterprises to compete by mechanizing labor-intensive tasks, such as milk chilling or grain milling, which were previously impossible without reliable power.

Major Initiatives Taken by India

- Lakhpati Didi Scheme: A flagship initiative targeting the creation of 3 crore “Lakhpati Didis” (SHG members earning ₹1 lakh+ annually) by integrating DRE technologies into businesses like food processing and textiles.

- PM Surya Ghar (Muft Bijli Yojana): Aims to establish 10,000 “Solar Villages” by 2030, encouraging rooftop solarization and women-led management of local grids.

- Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM): Focuses on de-dieselizing the farm sector by providing solar pumps, with specific mandates for women-led water user associations.

- Mission Shakti: Utilizes gender budgeting (which saw a record allocation in 2025-26) to fund clean-energy-powered livelihoods for women.

|

Challenges that Need to be Tackled

Despite the potential, structural “chokepoints” persist as of 2025–26:

- High Capital Intensity: Initial setup costs are prohibitive; for instance, a solar-powered bulk milk chiller can cost up to ₹25 lakh, a sum often beyond the reach of village-level SHGs without collateral.

- The Technical “Maintenance Gap”: Recent reports from remote districts in Jharkhand show that solar installations often lie defunct because the nearest technicians are men based in distant cities, and there is a lack of local female cadres to handle repairs.

- Patriarchal Land Norms: According to the Agriculture Census, women own only 13.9% of land in India. This lack of land titles remains a “Herculean task” when trying to secure formal bank loans for assets like solar irrigation pumps.

- Market Information Asymmetry: In regions like Himachal Pradesh, small-scale fruit processors continue to use expensive diesel generators because they lack awareness regarding available government subsidies for solar dryers.

Key Case Studies

- Chhattisgarh (Anjor Vision 2047): A state roadmap aiming to make renewable energy the backbone of the economy by creating 50,000 “green jobs” and utilizing the Bihan Mission (State Rural Livelihoods Mission) to train women as energy entrepreneurs.

- Odisha (Solar Silk Reeling): In districts like Keonjhar, solar-powered machines have replaced the drudgery of manual “thigh-reeling,” boosting weavers’ monthly incomes from ₹1,500 to over ₹6,000.

- IIT Bombay (SoUL Project): The Solar Urja Lamp (SoUL) project has successfully trained a cadre of “Solar Didis” in Bihar to assemble, distribute, and maintain solar lamps, creating a sustainable local service model.

|

Way Forward

- Asset Ownership Mandates: Policies should mirror the Ujjwala Yojana by mandating women as the primary or joint owners of energy assets to ensure they have legal control over the technology.

- Creating the “Oorja Sakhi” Cadre: Scaling vocational Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) training to build a local workforce of women technicians for last-mile maintenance.

- Financial Innovation: Implementing First Loss Default Guarantees (FLDG) and dedicated “Green Credit” lines to de-risk loans for women-led clean-tech startups.

- Panchayat Empowerment: Enabling Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) to use their Own Source Revenue (OSR) to partner with SHGs for “Energy-as-a-Service” models at the village level.

Conclusion

India’s journey to Net-Zero cannot be completed on the back of mega-parks alone. A just transition requires that the women at the periphery move to the center of the value chain. By scaling women-led DRE, India can simultaneously solve the trilemma of energy poverty, climate change, and gender inequality.

![]() 17 Feb 2026

17 Feb 2026