The Himalayan region is facing an alarming rise in climate-induced disasters, with over 4,000 deaths in 2025 alone.

Continued expansion of projects like the Char Dham highway into ecologically fragile zones raises concerns of an unfolding Himalayan ecocide driven by unsustainable development.

About Ecocide

- Meaning: Ecocide refers to the large-scale, widespread, or long-term destruction of ecosystems caused by deliberate or negligent human activities.

-

- It involves environmental harm that is severe enough to threaten the survival, health, or peaceful enjoyment of human and non-human life.

- Origin of the Concept: The term ecocide was coined in 1970 by biologist Arthur Galston in response to ecological destruction during the Vietnam War.

- The concept gained renewed global relevance due to climate change, biodiversity loss, and industrial environmental disasters.

- Proposed International Legal Definition: In 2021, an Independent Expert Panel proposed a legal definition of ecocide for inclusion in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

- Ecocide was defined as unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge of a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term environmental damage.

- The proposal seeks to recognize ecocide as the fifth international crime, alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression.

- Essential Elements: Ecocide involves environmental damage affecting large geographical areas and ecological systems.

- The damage caused is long-term or irreversible in nature.

- The harm results in serious disruption of ecosystem functions and human livelihoods.

- The destruction arises directly from anthropogenic actions, including those of states, corporations, or individuals.

- Illustrative Examples of Ecocide:

- Large-Scale Deforestation: Large-scale deforestation has caused irreversible biodiversity loss and climate instability.

- The Amazon rainforest deforestation has been widely cited as approaching a tipping point, threatening global climate regulation.

- Massive Oil Spills: Massive oil spills result in long-term marine ecosystem damage and loss of coastal livelihoods.

- The Deepwater Horizon oil spill (Gulf of Mexico) caused extensive ecological damage, with impacts persisting for over a decade.

- Industrial Pollution: Industrial pollution contaminates rivers, soil, and groundwater, leading to severe public health consequences.

- The Bhopal Gas Tragedy (1984) remains a classic example of long-term environmental and human damage caused by industrial negligence.

- Mining-Induced Environmental Destruction: Large-scale mining operations destroy entire landscapes and disrupt local ecological and social systems.

- Lithium mining in South America’s “Lithium Triangle” has led to groundwater depletion and ecosystem stress.

- Environmental Destruction During Armed Conflict: Armed conflicts often involve deliberate or collateral environmental destruction with long-term effects.

- The use of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War caused persistent soil contamination and ecological damage.

- Agent Orange was a chemical herbicide and defoliant used by the United States military during the Vietnam War (1961–1971).

About the Himalayan Crisis

- Environmental Volatility (The “Multipliers”): The Himalayas are inherently unstable, and climate change acts as a force multiplier for existing natural risks.

- Geological Fragility: As young fold mountains, the region lies in Seismic Zones IV and V.

- Unstable lithology and active fault lines (e.g., Main Central Thrust – MCT) make the terrain highly prone to earthquake-triggered landslides.

About Main Central Thrust (MCT)

- It is one of the most significant tectonic fault systems of the Himalayas, formed due to the ongoing collision between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate.

- The MCT is a major intracontinental thrust fault that separates:

- Higher Himalayan Crystalline (HHC) rocks in the north

- From Lesser Himalayan Sequence (LHS) rocks in the south

- Along the MCT, older, high-grade metamorphic rocks have been thrust over younger, lower-grade rocks, a classic example of compressional tectonics.

- It is geologically active, with evidence of recurrent reactivation over geological time.

-

- The Warming Gap: High-altitude regions warming ~50% faster than the global average has accelerated glacial retreat, generating hydro-meteorological hazards such as Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) and a ~200% rise in cloudbursts since 2010.

- Ecosystem Decay: Deforestation (Deodar loss) and mining-induced drainage obstruction have removed natural ecological “anchors”, resulting in soil erosion, slope instability, and mass wasting.

- Structural Malpractice (The “Triggers”): The crisis is intensified by human interventions that ignore regional carrying capacity.

- Engineering Failures: Standardized road designs (double-lane with paved shoulder- DL-PS) rely on vertical hill-cutting, violating the natural angle of repose, leading to 800+ active landslide zones along major corridors.

- DL-PS standard that mandates a 12-metre paved surface in an area demonstrably prone to disasters.

- Encroachment & Tunnelling: Hydropower tunnelling and urban expansion into floodplains and riverbeds have eroded natural buffering systems, culminating in disasters like the 2025 Dharali floods.

- MCT Violation: Infrastructure has expanded north of the Main Central Thrust (MCT)—a fractured, high-seismic-risk zone where large-scale construction was traditionally restricted.

- Governance & Socio-Economic Pressure: Institutional capacity and social preparedness lag behind the pace of physical development.

- Tourism Strain: Pilgrimage-driven mass tourism (Char Dham) proceeds without scientific carrying-capacity assessments, exerting seasonal pressure on fragile slopes, especially during the monsoon.

- Institutional Fragmentation: Multi-layered governance (District–State–Centre) causes coordination deficits, weak real-time monitoring, and delayed early-warning dissemination.

- Marginalization: Remote hill communities face healthcare and connectivity gaps, while tokenistic disaster drills fail to build genuine community resilience.

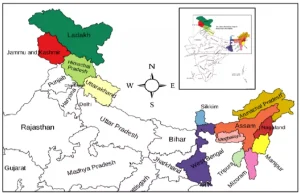

About Indian Himalayan Region (IHR)

- Geographical Spread: The IHR is spread across 13 Indian States and Union Territories (UTs).

- Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura, Assam, and West Bengal.

- It stretches over 2,500 km in length and covers about 16% of India’s geographical area.

- Population and Diversity: Home to nearly 50 million people.

- Inhabited by diverse ethnic communities such as Ladakhis, Bhutias of Sikkim, Tibetan Buddhists, and Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh, each with unique cultures, languages, and traditions.

- Known for pluralistic demographic, economic, environmental, social, and political systems.

|

Significance of the Himalayas to India

- Climate Regulator and Weather Controller: The Himalayas act as a natural climatic wall, shaping India’s weather and seasons.

- They force moisture-laden South-West monsoon winds to rise, causing rainfall over northern and central India.

- Without this barrier, much of the country would be dry and semi-desert. In winter, the mountains block cold winds from Central Asia, keeping the Indian plains warm, livable, and farm-friendly.

- “Water Tower” of India: The Himalayas are the main source of India’s freshwater.

- Major rivers such as the Indus, Ganga, Yamuna, and Brahmaputra originate from Himalayan glaciers and snowfields.

- These rivers support drinking water, farming, industry, and sanitation for nearly half of India’s population.

- The steep slopes also provide huge hydropower potential, making the region vital for renewable energy.

- Agricultural and Economic Backbone: Himalayan rivers carry nutrient-rich alluvial soil to the plains, creating the fertile Indo-Gangetic belt, India’s main food-producing region.

- The mountains also provide forest resources, including medicinal plants, herbs, and timber, supporting rural livelihoods.

- Additionally, the Himalayas are a major hub for tourism and pilgrimage, sustaining local economies in places like Kedarnath, Badrinath, Leh, and Manali.

- Defence and Strategic Importance: The Himalayas serve as India’s natural northern shield.

- Their rugged terrain and high mountain passes make large-scale invasions difficult.

- Control over strategic areas such as Ladakh and Siachen Glacier is crucial for national security, border surveillance, and military advantage, especially along borders with China and Pakistan.

- Biodiversity and Cultural Heritage: The Himalayas are a global biodiversity hotspot, home to rare species like the Snow Leopard, Red Panda, and Himalayan Monal.

- Culturally, they are revered as “Devbhoomi” (Land of the Gods) and are central to the spiritual traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism.

- The mountains host sacred rivers, pilgrimage routes, and ancient traditions that form the civilisational core of India.

India’s Himalayan Resilience Framework

- Leading Scientific Efforts: India has built a multi-agency monitoring system to track glacier retreat and improve disaster prediction in the Himalayas.

- Specialised Research Centres: The Himansh research station (established in 2016) and the Centre for Cryosphere and Climate Change Studies (C4S) at National Institute of Hydrology (NIH), Roorkee provide ground-level data to understand climate change impacts on glaciers and rivers.

- Monitoring the “Water Tower of Asia”: Scientific studies show glaciers are shrinking at different speeds—about 12.7 metres per year in the Indus Basin and nearly 20.2 metres per year in the Brahmaputra Basin.

- This information is vital for water security planning for nearly 600 million people living downstream.

- Unified Oversight: The Steering Committee on Monitoring of Glaciers (2023) ensures real-time data sharing among the Ministry of Jal Shakti, Ministry of Earth Sciences, and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), reducing delays caused by working in isolation.

- National Risk Reduction and Policy Integration: These initiatives shift Himalayan governance from post-disaster response to disaster prevention.

- GLOF and Landslide Risk Reduction: The National Landslide Risk Mitigation Project (NLRMP) and the National Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Risk Mitigation Programme (NGRMP, 2025) focus on hazard mapping, risk zoning, and location-specific safety structures.

- Climate-Resilient Infrastructure: Through the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), India is redesigning roads, bridges, and tunnels to survive rare but extreme weather events such as intense rainfall and cloudbursts.

- Policy Umbrella: The National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem (NMSHE), under the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), supports 11 State Climate Change Cells to design region-specific climate adaptation strategies.

- Community-Centric and Border Resilience: Policy now recognises that local communities are the first line of defence in the Himalayas.

- Local First Responders: The Aapda Mitra Scheme has trained over one lakh local volunteers in search, rescue, and relief Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), helping save lives during the crucial “Golden Hour” after disasters.

- Vibrant Villages Programme – Phase II (VVP-II): Launched in 2025 with an outlay of ₹6,839 crore, the scheme strengthens border villages through all-weather roads, digital connectivity, and climate-resilient livelihoods, reducing migration and improving border security.

- Ecosystem Protection: Projects like SECURE Himalaya (Government of India–United Nations Development Programme partnership) and the India–Switzerland Himalayan Climate Adaptation Programme (IHCAP) combine traditional knowledge with modern science to restore alpine grasslands, protect biodiversity, and revive drying mountain springs.

Associated Global InitiativesSendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030): Calls for risk assessment, resilience building, and early warning.

Paris Agreement (2015): Encourages adaptation and resilience against climate-driven disasters.

Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI, 2019): India-led global partnership for climate- and disaster-resilient infrastructure.

United Nations Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response (UN-SPIDER): Provides space-based information for disaster management and emergency response.

Associated Global Initiatives

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030): Calls for risk assessment, resilience building, and early warning.

- Paris Agreement (2015): Encourages adaptation and resilience against climate-driven disasters.

- Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI, 2019): India-led global partnership for climate- and disaster-resilient infrastructure.

- United Nations Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response (UN-SPIDER): Provides space-based information for disaster management and emergency response.

[/orange_table]

Systemic Shortcomings in Himalayan Disaster Preparedness and Recovery

- The “Information–Action” Gap: There is a clear gap between scientific data and people’s safety on the ground.

- Passive Surveillance: Agencies such as the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) and the Geological Survey of India (GSI) have strong satellite mapping systems, but monitoring of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) and unstable mountain slopes is not done in real time.

- This static data cannot keep pace with fast-changing disasters.

- Ineffective Communication: During the 2025 monsoon, large-scale Short Message Service (SMS) alerts were issued, but many failed to save lives.

- Alerts warned of danger but did not clearly explain where to evacuate, which routes to use, or the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to follow.

- Regulatory Weakening and “Engineering Overconfidence”: Development is often imposed on the mountains instead of working with their natural limits.

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Evasion: Large infrastructure projects are broken into smaller parts to avoid mandatory Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA).

- This hides the combined environmental damage being caused to the Himalayan region.

- Engineering Overconfidence: Engineers frequently try to stabilise damaged slopes using nets, bolts, and sprayed concrete (shotcrete) after aggressive road cutting.

- This ignores the fact that the Himalayas are young and fragile mountains, where such hard engineering solutions often fail.

- The “Carrying Capacity” Crisis: Human activity in the Himalayas has crossed the region’s natural limits.

- Uncontrolled Pressure: There are no scientifically fixed limits on the number of pilgrims or vehicles. During peak seasons, roads, towns, and emergency services are pushed far beyond their capacity.

- Encroachment: Continuous construction in river floodplains and earthquake-prone zones has increased damage. This was clearly seen in the high building collapse rates during the 2024–2025 floods.

- Short-Sighted Recovery Models: Post-disaster actions often create conditions for the next disaster.

- Speed over Stability: After floods or landslides, authorities focus on quickly restoring road connectivity. In the process, proper geological checks are skipped, and roads are rebuilt on the same unstable debris that collapsed earlier.

- Socio-Economic Delay: Long delays in compensation, rehabilitation, and livelihood support slow recovery, leaving remote Himalayan communities exposed to repeated disasters and long-term insecurity.

Way Forward

- Need for a New Policy Framework: The current trajectory reveals a systemic failure in governance, necessitating a shift toward the National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem (NMSHE) guidelines:

- Mitigating “Risk Multipliers”: Climate change intensifies erratic rainfall and glacial melt; infrastructure must be designed to withstand this “water peak phase” rather than contributing to it through poor muck dumping.

- Scientific Accountability: There is an urgent need to replace “hubris-driven” engineering (like retrofitting unstable slopes with Swiss bolts after damage is done) with pre-emptive geological surveys.

- Preserving the Bhagirathi Eco-Sensitive Zone: Large-scale deforestation and “translocation” of ancient trees are ecologically flawed; preserving the buffer zones is essential for water security and oxygen levels in snowmelt-fed streams.

- Governance and Regulatory Reset:

- Unified Himalayan Governance: Create a Himalayan Authority – a cross-state constitutional body covering all Himalayan States and Union Territories – to replace the current fragmented, state-wise approach and ensure common policies, standards, and coordination.

- Region-Specific Impact Assessment: Replace generic Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) with mountain-sensitive standards, including mandatory seismic risk checks and slope stability audits for all major projects, especially those above ₹50 crore.

- Carrying Capacity Enforcement: Legally fix daily limits on tourists, pilgrims, and vehicles in fragile zones based on scientific guidelines to prevent overcrowding, infrastructure stress, and disaster risk.

- Infrastructure and Engineering Reform:

- Hill-Sensitive Design: Replace aggressive road-widening models with mountain-friendly road designs that reduce hill cutting and protect natural slopes.

- “Build Less, Build Smart” Approach: Focus on strengthening existing roads, bridges, and tunnels instead of building new ones. All new infrastructure must be designed to survive extreme climate events.

- Zero-Muck Policy: Enforce strict control over construction waste (muck) using GPS tracking and monitoring systems, ensuring no dumping into rivers, which currently worsens floods and river overflow.

- Climate-Ready Infrastructure: Make disaster resilience a core rule in all Himalayan projects, not an afterthought.

- Early Warning Systems and Community Safety:

- Integrated Data System: Create a Himalayan Data Grid that combines satellite data, weather forecasts, and ground sensors into a real-time disaster dashboard for district officials and village leaders.

- People-Centric Alerts: Move beyond bulk SMS alerts to local-language voice calls, sirens, and valley-specific evacuation guidance, so warnings become actionable, not just informational.

- Spring Revival for Water Security: Expand spring rejuvenation programmes to revive drying mountain springs, ensuring drinking water availability, soil moisture, and forest fire prevention.

- Nature-Based and Ecosystem Solutions:

- Natural Slope Protection: Promote deep-rooted native trees (like oak and deodar) that naturally hold soil and stabilize slopes, instead of commercial plantation species that weaken hills.

- Forest and River Buffer Zones: Protect eco-sensitive zones, riverbanks, and forest buffers instead of relocating or clearing them, to secure water flow, oxygen levels, and biodiversity.

- Sustainable Tourism Model: Shift from mass tourism to low-impact eco-tourism, where tourism revenue directly supports forest protection, spring revival, and local livelihoods.

Conclusion

Resilience must be the cornerstone of Himalayan development. As the Sendai Framework reminds us, “Disasters are not natural, they are the consequence of risk built into society.” Aligning with SDG-11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG-13 (Climate Action), the future model must shift from control over nature to co-existence, and from project-driven growth to ecosystem-led governance.

Also Read | Disaster Management in the Indian Himalayan Region

![]() 24 Jan 2026

24 Jan 2026