Despite many education reforms, our system fails to understand the changing job market, leaving graduates unprepared and unemployable.

The Paradox of Educated Unemployment

- Educated unemployment refers to a situation where individuals with formal education, often higher education, are unable to find suitable employment matching their qualifications. In India, this paradox has deepened—as educational qualifications rise, employability and job prospects often decline.

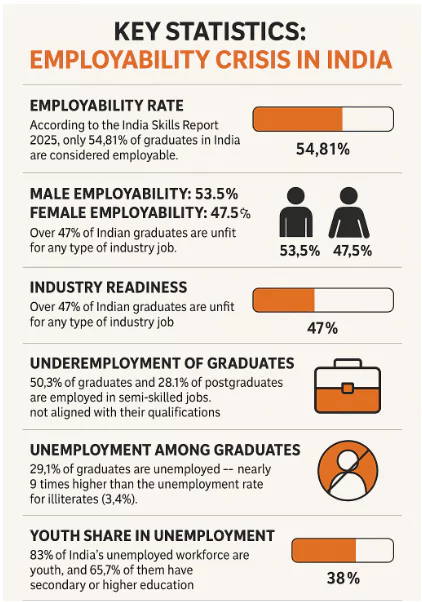

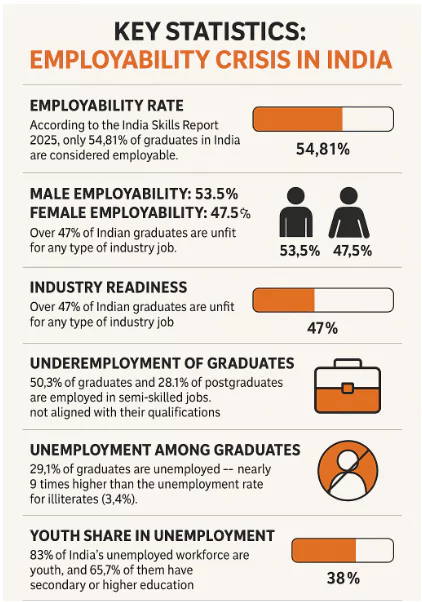

- According to the ILO–IHD India Employment Report 2024, over 83% of India’s unemployed workforce are youth, and more than 65% of them have secondary or higher education.

- The graduate unemployment rate is around 29.1%, almost 9 times higher than that of illiterates.

Why is It a Paradox?

- Education is traditionally associated with:

- Human capital formation

- Better employment prospects

- Social mobility and economic security

- Yet, in India:

- Degree holders are increasingly underemployed or jobless.

- Even elite institute graduates (e.g., IITs) face placement shortfalls.

- Half of employed graduates work in roles below their qualifications.

- This constitutes the paradox—education no longer guarantees employment, undermining the very rationale for pursuing formal education.

Causes of Educated Unemployment

- Excess Supply of Graduates, Limited Job Demand: Universities rose from 642 (2011–12) to 993 (2018–19), with 3.74 crore students enrolled.

- However, graduate job creation has not kept pace, leading to market oversaturation.

- Poor Quality of Higher Education: NEP 2020 emphasizes course flexibility, but neglects pedagogy and curriculum reforms

- Many private colleges lack qualified faculty and infrastructure, leading to poor learning outcomes.

- Skill Mismatch Between Education and Industry Needs: Graduates lack skills in communication, problem-solving, digital literacy, and technical domains.

- A shocking 47% of graduates are unfit for industry roles despite formal education.

- Structural and Systemic Economic Issues

- Jobless growth: India lost 9 million jobs (2011–18); manufacturing shed 3.5 million.

- “Make in India” failed to create jobs due to capital-intensive focus.

- Lack of industry–academia collaboration (e.g., no industry members in NEP drafting panel) hinders curriculum relevance.

Category Normalized Citation Impact (CNCI)

- It is a metric used to assess the citation performance of research publications, particularly within the context of Indian research.

- CNCI of a document is calculated by dividing the actual count of citing items by the expected citation rate.

- CNCI helps determine if a publication has been cited more or less than expected for its field, publication type, and year.

|

- Poor Research Output and Innovation Ecosystem: India ranks 16th in Category Normalized Citation Impact (CNCI) among G-20 nations; improvement from 17th is marginal.

- Public R&D projects like Akash tablet and IMPRINT lack transparent outcomes, despite high funding.

- Lack of indigenous technology and patent filings (e.g., Samsung leads in Bengaluru patents) reflects weak innovation foundations.

Consequences

- Underemployment and Wastage of Human Capital: A large share of educated youth is working in jobs below their qualifications:

- 50.3% of graduates and 28.1% of postgraduates are in semi-skilled roles, indicating underutilization of their education.

- Poor Return on Investment in Education: Students and families spend significantly on higher education expecting upward mobility, but with 47% of graduates unfit for industry,

- The result is low returns on both private (student) and public (government) investment in education.

- Brain Drain and Migration Aspirations: Even premier institutes like IITs report significant placement gap, driving talented youth to seek jobs abroad or in unrelated sectors.

- This undermines India’s efforts to retain skilled manpower for nation-building.

- Youth Disillusionment and Mental Distress: High unemployment among educated youth fuels frustration, hopelessness, and anxiety.

- This can escalate into social unrest, political radicalization, or withdrawal from economic participation (disheartened labor).

- Widening Social Inequality: Employment is increasingly skewed by gender, caste, and region:

- Female unemployment is as high as 34.5% for graduates.

- Declining Faith in the Education System: When degrees do not result in employment, it erodes public trust in the education system, especially in Tier 2 and Tier 3 institutions.

Government Initiatives to Tackle Education–Employment Mismatch

- National Education Policy (NEP) 2020

- Objective: Curriculum flexibility, vocational training integration, and skill-based learning.

- Challenges:

- NEP’s multiple entry–exit system has led to low-quality e-commerce jobs, not meaningful employment.

- Lacks proper implementation methodology and no industry participation in drafting committee.

- Overfocus on course selection, neglecting course content relevance and quality.

- Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY)

- Objective: Provide skill certification and short-term training to youth.

- Challenges:

- Poor placement outcomes and weak monitoring mechanisms.

- Does not sufficiently bridge the industry skill gap.

- Skill India Mission (2015)

- Objective: Create a skilled workforce aligned with market demand.

- Coverage Gaps: India still has only 2.7% of the population vocationally trained, compared to 96% in South Korea.

- Mostly limited to entry-level, low-paying jobs.

- Make in India:

- Objective: Promote manufacturing and job creation in labor-intensive sectors.

- Issues:

- Manufacturing jobs declined by 3.5 million between 2011–12 and 2017–18.

- Focus remained on capital-intensive sectors, failing to absorb skilled labor.

- Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY) (2021)

-

- Objective: Provide rural youth with market-linked skills and employment.

- Constraints: Limited awareness and weak rural infrastructure affect effective outreach and uptake.

- National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS) (2016)

-

- Objective: Promote apprenticeship in industry and incentivize employers.

- Constraints: Low participation of firms and lack of integration with university curricula limit impact.

Challenges in Tackling the Education–Employment Mismatch in India

- Poor Implementation of Educational Reforms: NEP 2020, though ambitious, remains largely on paper.

- Reforms are limited to flexible course choices, without addressing curriculum quality, pedagogy, or industry integration.

- No roadmap for skill-linked learning outcomes, resulting in little change at ground level.

- Weak Industry–Academia Linkages: NEP 2020’s drafting committee had no industry representation, disconnecting policy from market needs.

- Universities lack real-time feedback loops from employers to revise courses, offer internships, or align competencies.

- Inadequate Skill Development Frameworks: Skill development schemes like PMKVY and Skill India suffer from:

- Low placement rates

- Certification inflation without actual skill-building

- Poor tracking of long-term employment outcomes.

- Degree-Centric, Not Skill-Centric Education: The system still emphasizes degree acquisition over employability.

- Courses rarely build soft skills, problem-solving ability, or digital literacy needed in modern workplaces.

- Inequitable Access and Regional Disparities: Rural areas and Tier 2/3 institutions lack exposure, infrastructure, and corporate partnerships.

- High graduate unemployment in Telangana (25.1%), Bihar (23%), and Andhra Pradesh (22.2%) shows spatial inequality.

- Gender and Social Barriers: Female unemployment (34.5%) is significantly higher than male (26.4%) despite growing education levels.

- Social norms and lack of workplace support restrict women’s labor force participation.

- Fragmentation and Overlap in Government Schemes: Multiple overlapping programs (NEP, PMKVY, DDU-GKY, NSDC initiatives) lack coordination, monitoring, and outcome tracking.

- No centralized employability dashboard exists to measure impact across schemes.

Way Forward: Solving the Education–Employment Disconnect

- Align Curriculum with Industry Needs: Revise higher education curricula to reflect real-world skill requirements such as communication, critical thinking, digital literacy, and problem-solving.

- Over 47% of graduates are deemed unemployable due to such skill gaps.

- NEP reforms must shift from flexibility to content quality and pedagogy improvement.

- Expand Vocational and Digital Skill Training: Make vocational education integral to all degree programs and scale digital skills training.

- Focus on job-ready certifications tied to sector-specific demands.

- Promote Region-Specific Skilling and MSME Job Growth: Tailor skill development to local industry needs (e.g., textiles in Tamil Nadu, tourism in Himachal).

- Encourage MSMEs and agro-industries that absorb local talent.

- Gender-Inclusive Employment Policies: Incentivize women’s employment with flexible work arrangements, childcare support, and safe workplaces.

- Female graduate unemployment is 34.5%, far higher than male unemployment (26.4%).

- Improve Data-Driven Monitoring of Outcomes: Establish a national tracking system for graduate outcomes, placement rates, and job tenure across institutions.

- Many schemes like PMKVY and DDU-GKY lack long-term tracking of job retention.

- Promote Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment: Provide credit, mentorship, and incubation for student entrepreneurs.

- Helps reduce over-reliance on government or corporate jobs.

- Encourages job creators, not just job seekers, especially in tech, agri-business, and services.

Conclusion

India’s education–employment disconnect demands urgent reforms to align curricula with industry needs, strengthen vocational training, and foster industry–academia collaboration. Without addressing skill mismatches and job creation, the demographic dividend risks becoming a demographic liability, threatening economic growth and social stability.

![]() 14 May 2025

14 May 2025