Recent Israel’s preemptive strikes and Iran’s retaliatory missiles both invoke self-defense, raising ethical questions about proportionality and legitimacy under international law.

About Self-defense in International Relations

- Self-defense is a fundamental principle in international law and ethics, rooted in the protection of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and human rights.

- Governed by Article 51 of the UN Charter, which permits force only in response to an “armed attack” and subject to necessity and proportionality.

- However, in an increasingly interconnected world—where conflicts often involve non-state actors, cyberattacks, and anticipatory strikes—the ethical and legal scope of this right is under intense scrutiny.

Types of Self-Defence in International Law

- Reactive (Actual) Self-Defence: Response to a real, ongoing armed attack.

- Legality: Clearly supported by Article 51 of the UN Charter.

- Ethical Standing: Strong—based on right to survival and sovereignty.

- Example: Military response after a missile strike on national territory.

- Preemptive Self-Defence: Action against a likely threat, where attack is not immediate but expected in the near term.

- Difference from Anticipatory: Less urgency, more strategic judgment involved.

- Legality: Highly contested; not formally legal under UN Charter.

- Example: Destroying a suspected nuclear site in another country without proof of imminent use.

- Preventive Self-Defence: Military action to prevent a possible, future threat that may or may not materialize.

- Legality: Widely regarded as illegal under international law.

- Example: Invasion of a country fearing it might develop hostile capability in 10 years.

- Collective Self-Defence: Defence undertaken to protect another state upon its request after it is attacked.

-

- Legality: Allowed under Article 51; must be reported to the UN Security Council.

- Example: NATO’s collective defence action post-9/11.

Legal Framework for Self-Defence in International Law

- United Nations Charter (1945)

-

- Article 2(4) – Prohibition of Use of Force: General prohibition on the use or threat of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

- Self-defence is the only exception, along with Security Council authorization under Chapter VII, Article 51.

- Article 51 – Right to Self-Defence: A UN member can use force in self-defence after an armed attack, but must report it to the Security Council, which retains ultimate authority to act for peace.

About United Nations Charter

- Signed on 26 June 1945, in San Francisco, and came into force on 24 October 1945.

- Serves as the foundational treaty of the United Nations, aiming to prevent future wars through collective security, diplomacy, and cooperation.

|

- Security Council Practice and Resolutions

- UNSC Resolution 1373 (2001): Passed after 9/11.

- Recognized self-defence against non-state actors, even across borders.

- Marked a shift in traditional interpretations of Article 51.

- UNSC Resolution 2249 (2015): Against ISIS.

- Called on states to take “all necessary measures” in accordance with international law, effectively endorsing collective self-defence against terrorist groups.

- Customary International Law

- Caroline Doctrine (1837): Foundation for anticipatory self-defence.

- Sets three criteria:

- Necessity of self-defence must be “instant, overwhelming”

- No choice of means or moment for deliberation

- Proportionality of the response.

- Nicaragua Case (ICJ, 1986): Differentiated between armed attack (triggers Article 51) and lesser forms of force (e.g., threats or interventions).

- Declared collective self-defence requires a request from the attacked state.

- Oil Platforms Case (ICJ, 2003): Reinforced that self-defence must meet necessity and proportionality.

- Also required clear evidence of an armed attack.

- “Unable or Unwilling” Doctrine: Permits use of force in self-defense against non-state actors in a host state deemed “unable or unwilling” to neutralize the threat.

- US invoked it for 2011 bin Laden operation in Pakistan and 2014 airstrikes against ISIS in Syria.

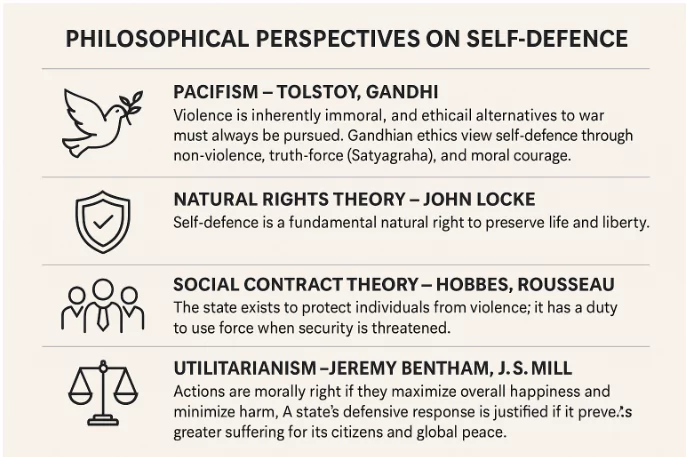

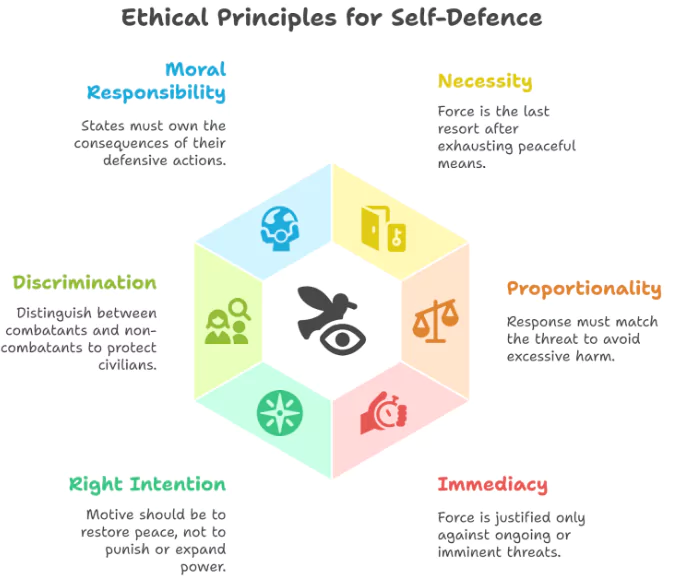

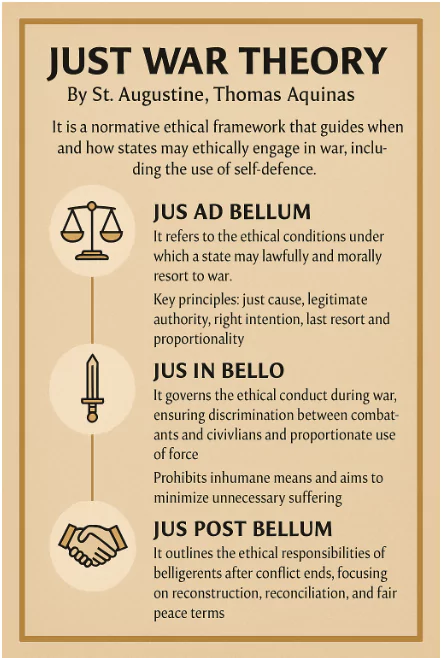

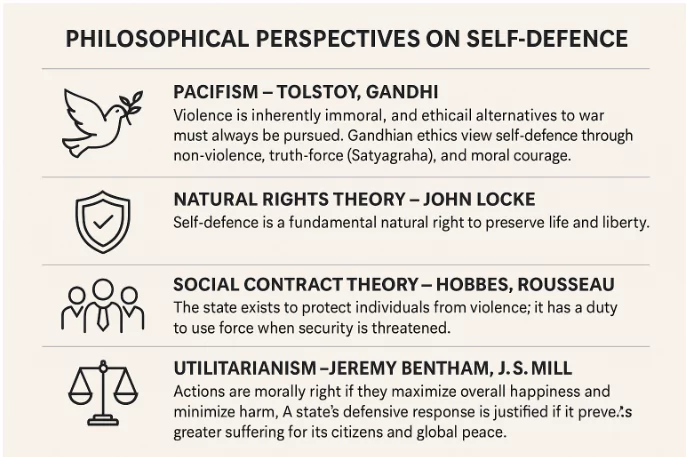

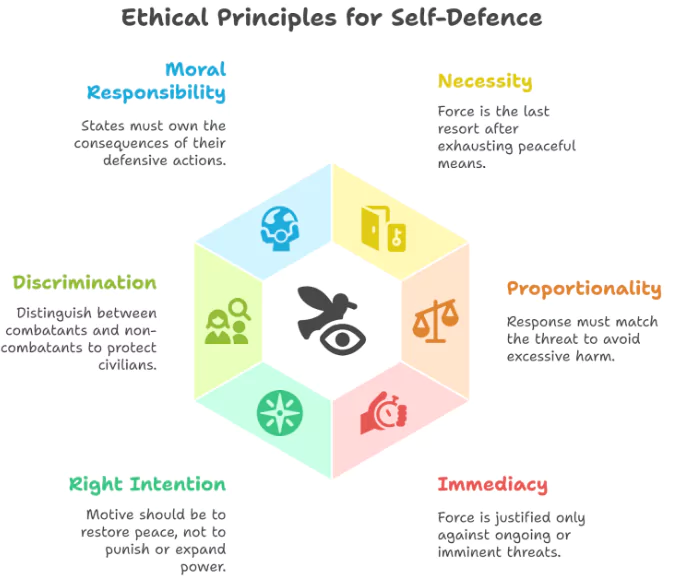

Ethical Principles Governing Self-Defence

- Necessity: The use of force must be the only viable option to prevent or repel an armed attack.

- All peaceful means—diplomacy, negotiation, arbitration—must have been exhausted.

- Proportionality: The defensive response must be commensurate with the scale and nature of the threat.

- Avoids excessive harm, especially to civilians or infrastructure.

- Immediacy / Imminence: Force should be used only in response to an ongoing or imminent threat.

- Right Intention: The motive behind self-defence must be to restore peace and security, not to punish or expand power.

- Discrimination / Civilian Immunity: Combatants must be distinguished from non-combatants; force must target only legitimate military objectives.

- Moral Responsibility and Accountability: States must take moral ownership of the consequences of their defensive actions, including unintended civilian harm.

- Requires transparency, internal review, and external oversight.

Ethical Dilemmas in Self-Defence

- Security vs. Sovereignty: Self-defence actions may conflict with the sovereign rights of another state.

- Cross-border strikes on terrorist camps often violate host nation sovereignty.

Preemptive vs. Preventive Action: Acting on intelligence before an attack occurs raises ethical concerns.

Preemptive vs. Preventive Action: Acting on intelligence before an attack occurs raises ethical concerns. -

- Preemptive actions against perceived threats risk being based on speculation.

- Proportionality vs. Deterrence: States may exceed proportional limits to send a strong deterrent message.

- Aerial bombings in response to minor incursions reflect ethical imbalance.

- Civilian Protection vs. Military Objective: Striking legitimate targets hidden among civilians risks harming innocents.

- Drone operations in populated areas often result in collateral casualties.

- Right Intention vs. Strategic Gain: Self-defence may be ethically compromised by underlying political motives.

- Military interventions are sometimes cloaked in moral language to justify regime goals.

- Collective Defence vs. Consent: Assisting an ally without clear consent can undermine their autonomy.

- Powerful states sometimes invoke collective defence unilaterally.

- Short-Term Gain vs. Long-Term Peace: Immediate use of force can jeopardize prospects for sustainable peace.

- Prolonged retaliation tends to escalate regional instability.

- Justice vs. Revenge: Self-defence may cross into punitive or retaliatory conduct.

- Continued strikes long after the original threat may become acts of retribution.

Ethical Challenges to Self-Defence

- Vagueness of ‘Imminent Threat’ Justification: The undefined scope of “imminence” allows states to justify unlawful preemptive action.

- The Caroline standard is often stretched to rationalize anticipatory strikes.

- Civilian Casualties and Proportionality Violation: Even targeted self-defence measures frequently harm non-combatants.

- Drone strikes on militant leaders in populated areas breach ethical restraint.

- Evasion of UN Oversight: Many states ignore Article 51’s reporting obligation, weakening global accountability.

- Post-strike notifications are often delayed or manipulated.

- Ambiguity in Dealing with Non-State Actors: Retaliating against insurgents in third states blurs legal and moral lines.

- Attribution becomes ethically difficult when proxies operate from weak states .

- Strategic Interests Framed as Moral Necessity: Self-defence is sometimes used to camouflage geopolitical or economic agendas.

- Regime change or regional dominance may be disguised as defensive action.

- Erosion of Global Peace Norms: Frequent invocation of self-defence undermines collective security principles.

- Routine unilateralism undercuts the UN’s authority and war-restraint mechanisms .

- Technology-Driven Ethical Disengagement: Remote warfare tools reduce human connection to violence and weaken moral checks.

- Autonomous drones and cyber attacks obscure direct ethical accountability

Self-Defence in Indian Foreign Policy

- Constitutional & Legal Backdrop:

- Article 51 of the Indian Constitution promotes international peace and arbitration, aligning India with the UN Charter.

- India supports sovereign equality, non-intervention, and the inherent right to self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter.

India’s Approach to Self-Defence: Principles

|

| Principle |

Indian Stance |

| Strategic Restraint |

Avoids excessive retaliation; prefers calibrated responses. |

| Proportionality |

Maintains ethical and legal thresholds in military actions. |

| Sovereignty Respect |

Upholds non-interference, unless clear aggression occurs. |

| Credible Deterrence |

Uses firm but restrained messaging (e.g., surgical strikes). |

| Responsibility Doctrine |

Holds states accountable for cross-border terror activities. |

- Key Doctrinal and Operational Milestones

- Operation Meghdoot (1984): India occupied Siachen in anticipation of Pakistani troop movement.

- A case of strategic preemption rooted in territorial self-defence.

- Kargil Conflict (1999): India exercised actual self-defence against Pakistani intrusion on Indian soil.

- Demonstrated restraint by not crossing the LoC despite provocation.

- Surgical Strikes (2016): Carried out across LoC after the Uri terror attack by non-state actors.

- Invoked self-defence against non-state actors in foreign territory.

- Balakot Air Strikes (2019): Retaliation for Pulwama suicide bombing on Indian paramilitary forces.

- Justified as a non-military preemptive action targeting terrorist camps.

- Operation Sindoor (2025): India exercised anticipatory self-defense against Pakistan-based terrorist camps following the Pahalgam attack, targeting non-state actors with precision strikes.

- Demonstrated restraint by initially avoiding civilian/military infrastructure and pursuing diplomatic outreach to justify actions globally, despite Pakistan’s retaliatory escalation.

- Ethical Positioning in Indian Thought

-

- Gandhian Legacy: Non-violence and diplomacy form the moral foundation of India’s global posture.

- Kautilyan Realism: Recognizes dharmic justification of self-defence in statecraft.

- Indian foreign policy balances moral restraint with decisive action when national security is endangered.

Way Forward

- Codify ‘Imminent Threat’ in International Law: Define “imminent threat” clearly to distinguish legitimate anticipatory defence from pretextual aggression.

- Current ambiguity allows states to exploit grey zones for unjustified use of force.

- Strengthen UN Oversight Mechanisms: Make Article 51 reporting mandatory with independent review by the Security Council.

- Timely accountability can deter misuse of self-defence claims.

- Regulate Use of Force Against Non-State Actors: Develop a binding international framework for cross-border action against terrorist groups.

- Evolving threats demand clarity on sovereignty vs. security dilemmas.

- Ensure Proportionality and Civilian Protection: Mandate international monitoring of civilian impact in self-defence operations.

- Ethical credibility hinges on protecting non-combatants.

- Promote Regional Security Pacts with Clear Protocols: Encourage localized defence agreements (like ASEAN, SCO) with pre-agreed red lines.

- Shared frameworks can reduce unilateralism and escalation.

- Incorporate Ethics Education in Military Doctrines: Embed ethical training in use-of-force decision-making at national levels.

- Morally conscious leadership reduces excess and avoids legal violations.

- Balance Strategic Deterrence with Moral Restraint: Adopt doctrines that assert defensive readiness without glorifying preemptive violence.

- Combining realism with ethics upholds both security and legitimacy.

Conclusion

The ethics of self-defense, as seen in the Israel-Iran conflict and India’s foreign policy, demand a delicate balance between necessity, proportionality, and respect for sovereignty. India’s restrained approach, exemplified by Operation Sindoor, offers a model for ethical self-defense, urging global adherence to international law and diplomacy to prevent escalation and uphold peace.

![]() 24 Jun 2025

24 Jun 2025

Preemptive vs. Preventive Action: Acting on intelligence before an attack occurs raises ethical concerns.

Preemptive vs. Preventive Action: Acting on intelligence before an attack occurs raises ethical concerns.