On September 29, the world observes the International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste (IDAFLW) to highlight the global crisis of food wastage.

- Nearly one-third of all food produced globally is lost or wasted.

Key Global Findings Highlighted on the IDAFLW

- Post-Harvest Losses: 13% of global food (about 1.25 billion tonnes) was lost after harvest but before reaching retail shelves in 2021.

- Consumer-Level Waste: 19% of food (around 1.05 billion tonnes) was wasted at households, retail, and food services in 2022.

- Household Contribution: Households generate 60% of global food waste, highlighting the impact of consumer behaviour.

- Food Insecurity: In 2023, about 28.9% of the world’s population (2.33 billion people) suffered from moderate or severe food insecurity, while 1 in 11 people faced hunger.

- Climate Impact: Food loss and waste contribute 8–10% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, more than the aviation and shipping sectors combined.

About Food Loss and Food Waste

- Food Loss occurs between the farm gate and the market, mainly during harvesting, transport, and storage.

- It includes crop damage from sudden rains after harvest, deterioration of perishables like fruits and vegetables before reaching markets, and spoilage in storage due to pests such as rats or poor handling.

- Food Waste takes place at the retail and consumer levels.

- It is seen when supermarkets reject produce for cosmetic reasons, households overcook or discard leftovers, or when customers over-serve themselves and waste food on the plate.

|

India’s Foodgrain Production and Losses

- Record Production: According to the Third Advance Estimates (2024–25), India achieved a record foodgrain output of 353.96 million tonnes, including 117.51 million tonnes of wheat and 149.07 million tonnes of rice.

- India is the second-largest producer of food grains globally, yet faces persistent post-harvest losses that undermine both farmer incomes and national food security.

- Economic Burden of Losses: A NABARD Consultancy Services (NABCONS) study, 2022, commissioned by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries (MoFPI), estimated that post-harvest losses cost India nearly ₹1.5 trillion annually, equivalent to 3.7% of agricultural GDP.

- Such massive losses translate into wasted water, energy, and labour, while reducing availability of food for millions.

- Crop-wise and Perishable Losses: Staple crops continue to face significant losses: paddy at 4.8% and wheat at 4.2%.

- Perishables like fruits and vegetables are even more vulnerable, with losses ranging between 10–15%, reflecting inefficiencies in storage, handling, and transport.

- Climate Impact of Food Loss: A 2023 joint study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), National Institute of Food Technology Entrepreneurship and Management (NIFTEM), and the Green Climate Fund (GCF) found that food losses in India generate over 33 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions annually.

- Cereals, especially paddy (due to methane intensity), and livestock products contribute significantly to these emissions, aggravating climate change and environmental degradation.

Food Grain Storage Systems in India

- Types of Storage Systems: There are various methods of storing foodgrains, and some of the key ones include:

- Centralized storage: Managed mainly by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and State Agencies. Ensures procurement, storage, and distribution of grains under the Central Pool.

- Cold storage: Used for perishables such as fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meat, and seafood. Helps reduce post-harvest losses and maintain nutritional quality.

- Decentralized storage: Implemented through Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS), rural godowns, and on-farm storage by farmers. Ensures local availability and reduces transportation costs.

|

Food Grain Storage Systems in India

|

| Centralized Storage of Food Grains |

- FCI as nodal agency: Responsible for procurement, storage, and distribution of foodgrains under the Central Pool. Procurement may be done directly by FCI or by State Government Agencies (SGAs). Grains procured by SGAs are handed to FCI, with costs reimbursed.

- Objective: To safeguard farmer incomes through procurement at Minimum Support Price (MSP), maintain buffer stocks, and stabilize food prices.

- Infrastructure: Grains are stored in covered godowns, warehouses, and modern steel silos, ensuring protection and quality maintenance.

- Public Distribution System (PDS): Centralized stocks form the backbone of PDS, ensuring nationwide food security. Surpluses are moved to deficit states.

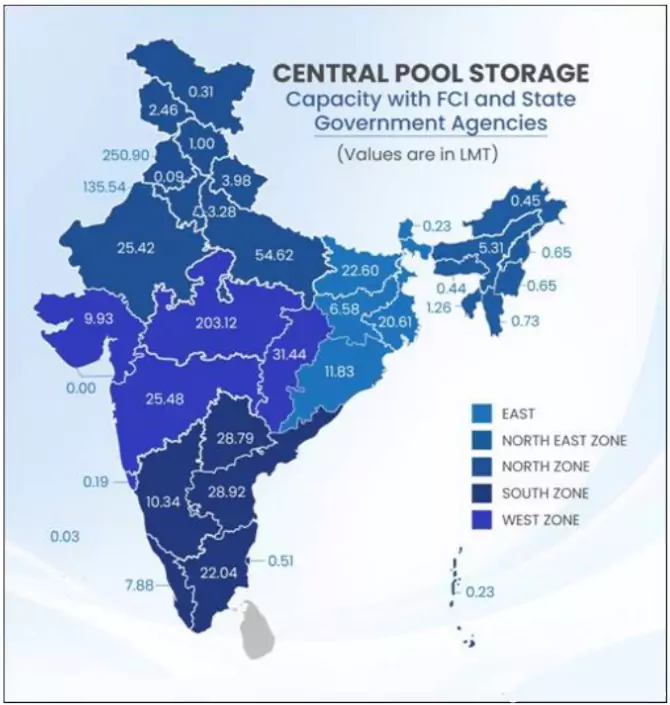

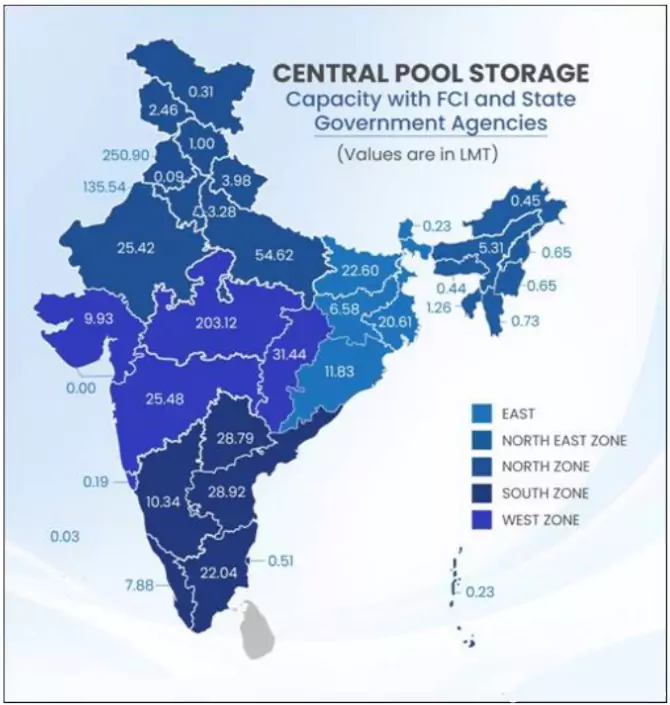

- Capacity (July 2025): Total 917.83 LMT with FCI and State Agencies.

- Covered storage: Fully roofed/walled structures like warehouses and silos.

- Cover and Plinth (CAP) storage: Grains stored on elevated plinths using wooden crates (dunnage) for ventilation and safety.

|

| Cold Storage Infrastructure |

- Role: Essential for perishable commodities (fruits, vegetables, dairy, meat, seafood). Prevents quality deterioration and extends shelf life.

Facilities included: Pre-cooling, weighing, sorting, grading, packaging, Controlled Atmosphere (CA) storage, blast freezing, and refrigerated transport (reefer vans). Facilities included: Pre-cooling, weighing, sorting, grading, packaging, Controlled Atmosphere (CA) storage, blast freezing, and refrigerated transport (reefer vans).- Impact: Minimizes post-harvest losses, ensures marketable surplus, and supports exports of perishable goods.

- Government support: Financial assistance provided through schemes such as Pradhan Mantri Kisan SAMPADA Yojana (PMKSY) and Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF).

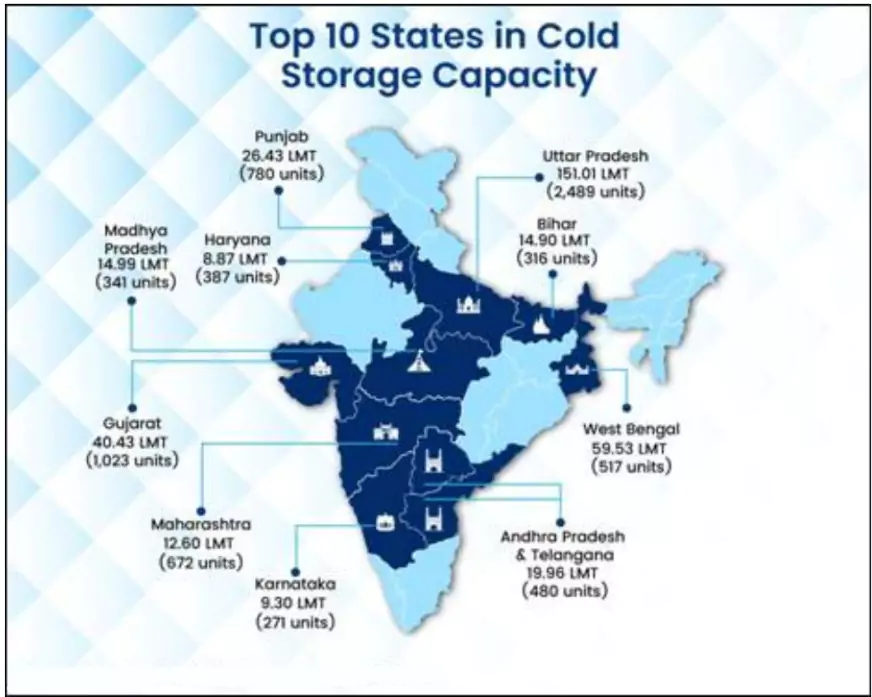

- Status (June 2025): 8,815 cold storages across India with a combined capacity of 402.18 Lakh MT.

|

| Decentralized Storage & PACS Role |

- Decentralized Procurement Scheme (DCP): Introduced in 1997–98, allowing State Governments to directly procure, store, and distribute foodgrains under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and other welfare schemes.

- Advantages: Encourages local procurement, saves transportation costs, and ensures supply of regionally preferred grains.

- Role of PACS (Primary Agricultural Credit Societies):

- Function as the grassroots arm of cooperative credit structure.

- Create village-level storage capacities ranging from 500–2000 MT.

- Serve both as procurement centres and Fair Price Shops (FPS).

- Help farmers by enabling local storage, reducing losses, and ensuring better price realization.

- Government push for modernization:

- Computerization project: Approved with an outlay of ₹2,516 crore to improve record-keeping, transparency, and efficiency.

- Expansion: As of June 2025,

- 73,492 PACS computerized,

- 5,937 new PACS registered, expanding outreach and strengthening the rural storage system.

|

Key Objectives of Grain Storage

- Reducing Post-Harvest Losses: Proper storage, including cold storage and modern warehouses, significantly reduces the wastage of agricultural produce.

- Ensuring Food Security: Maintaining a buffer stock of food grains is essential for national food security and for distribution under programmes like the National Food Security Act (NFSA).

- Preventing Distress Sales: Access to storage facilities allows farmers to hold their produce and sell it at an optimal time, avoiding distress sales and helping them realise better prices.

- Price Stabilisation: Maintaining strategic buffer stocks helps protect consumers from extreme price volatility in essential commodities.

- Maintaining Quality: Scientific storage ensures that food grains remain fit for human consumption by controlling factors like moisture and pests.

Need for Grain Storage in India

- National Food Security Act (NFSA): The NFSA, 2013, aims to provide food security to eligible beneficiaries by ensuring access to adequate food grains at subsidised prices.

- To achieve this objective, it requires robust and scientific storage facilities that prevent deterioration, maintain nutritional quality, and enhance the longevity of grains and seeds.

- Population Pressure: India has only 11% of the world’s cultivable area but supports 18% of the global population.

- With a population exceeding 1.4 billion, uninterrupted food supply depends critically on adequate storage infrastructure to ensure that grains reach all sections of society throughout the year.

- Shortage of Storage: Despite record foodgrain production of 332.3 million metric tonnes (MMT) in 2023–24 and a projected ~354 MMT in 2024–25, the available storage capacity is insufficient to meet demand.

- Inadequate storage leads to post-harvest losses estimated at 10–15% of total production, caused by pests, moisture, and improper handling.

- Globally, other countries maintain surplus storage capacity (~131%), whereas India faces a significant shortfall (~47%).

- Regional Disparities: Storage capacity in India varies widely across regions.

- Some southern states have capacities above 90%, while northern states, which produce a large portion of wheat and rice, have capacities below 50%.

- Heavy reliance on central warehouses managed by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and state agencies increases transportation costs and the risk of spoilage during transit.

- Strategic Importance of Storage: Adequate grain storage serves multiple purposes.

- It safeguards buffer stocks under NFSA, stabilizes prices by protecting farmers from distress sales and consumers from inflation, and ensures nutritional security by preventing fungal contamination, pest damage, and aflatoxins.

- Furthermore, sufficient storage infrastructure supports disaster preparedness by maintaining supplies during droughts, floods, or pandemics.

- From an environmental perspective, reducing storage losses also lowers greenhouse gas emissions, aligning with Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG 13) – Climate Action.

India’s Initiatives to Strengthen Foodgrain Storage

- National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013: Provides subsidised food grains to ~67% of the population, requiring robust buffer stock and storage systems.

Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF): Launched in 2020 to finance post-harvest and farm-gate infrastructure with interest subvention and credit guarantee.

Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF): Launched in 2020 to finance post-harvest and farm-gate infrastructure with interest subvention and credit guarantee. -

- ₹73,155 crore sanctioned for 1.27 lakh projects (Sept 2025) worth ₹1.17 lakh crore, including warehouses and cold stores.

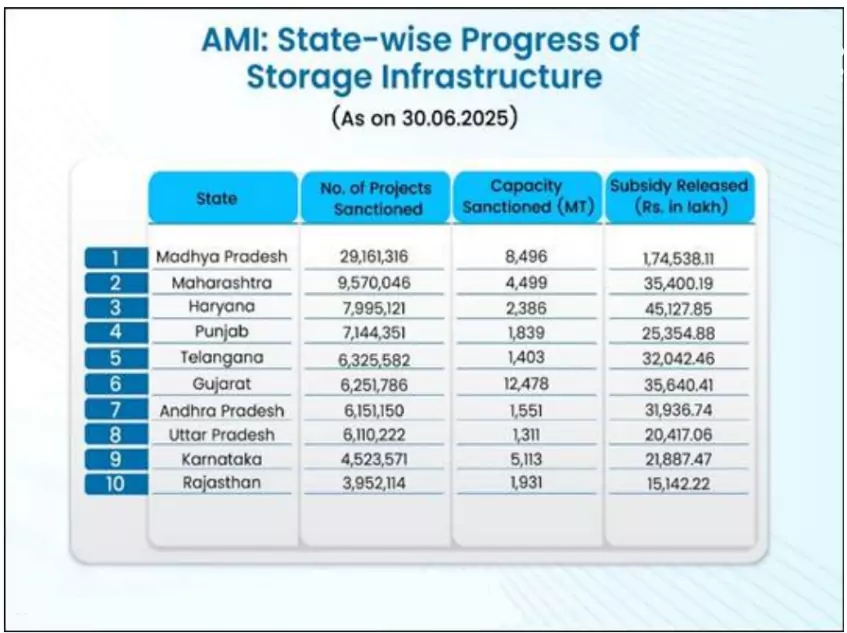

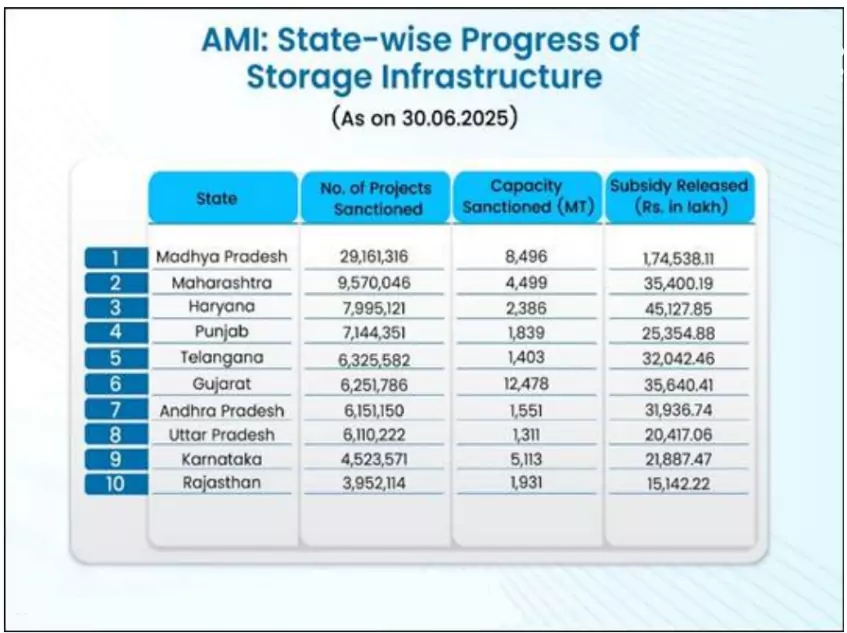

- Agricultural Marketing Infrastructure (AMI): Part of ISAM; supports construction/renovation of godowns and warehouses.

- By June 2025, 49,796 projects across 27 states created 982.94 lakh MT capacity with ₹4,829.37 crore subsidy.

- Pradhan Mantri Kisan SAMPADA Yojana (PMKSY): Builds modern food processing and cold chain infrastructure.

- As of June 2025, 1,601 projects approved (1,133 operational) adding 255.66 lakh MT annual processing capacity.

- Capital Investment Subsidy for Cold Storages: Provides 35% subsidy (general areas) and 50% subsidy (NE, hilly, scheduled areas) for cold/CA storages of 5,000–20,000 MT.

- Promotes scientific storage, shelf-life extension, and value chain efficiency.

- Sahakar-se-Samriddhi: To address storage challenges, the government approved the World’s Largest Grain Storage Plan in the Cooperative Sector (May 2023).

- Under this plan, Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS) are being developed as multi-functional units to provide storage and procurement services, carry out processing, sorting, and grading of grains, operate Fair Price Shops (FPS), and establish value-addition hubs.

- These initiatives aim to bring storage closer to farmers, reduce transportation losses, improve efficiency, and ensure better price realization for producers.

- By Aug 2025, 11 PACS godowns were completed; 500+ PACS identified for expansion.

- Steel Silos Initiative: Promotes mechanized bulk storage to reduce losses.

- By June 2025, 48 silos (27.75 LMT) completed, 87 silos (36.875 LMT) under construction, 54 silos (25.125 LMT) in tender stage.

- Asset Monetization (FCI Land): Constructs godowns on vacant FCI land. 177 sites identified with potential 17.47 LMT capacity (July 2025).

- Central Sector Scheme – “Storage & Godowns”: Focuses on North East, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Kerala.

- Outlay of ₹379.50 crore (NE) & ₹104.58 crore (others) fully released till 2025.

- Private Entrepreneurs Guarantee (PEG) Scheme: Started in 2008 in PPP mode.

- Provides government guarantee for hiring storage capacity, encouraging private investment in modern warehousing.

- Digital & Climate Commitments: Monitoring of SDG 12.3.1 (Food Loss & Waste) under the National Indicator Framework, along with digital procurement systems and AI-based pilots for tracking stock movement.

Global Initiatives & World Best Practices:

- International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste (IDAFLW): Observed on 29th September, led by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), to raise awareness of the global challenge of food loss and waste.

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.3: Aims to halve per capita global food waste at retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains by 2030.

- European Union (EU) Food Loss and Waste Prevention Programme: Focuses on farm-to-fork strategies, mandatory reporting of food waste, redistribution to food banks, and promotion of a circular economy.

- United States – Food Recovery Challenge (EPA): Encourages organisations to prevent food waste by donating surplus food and recycling unavoidable waste into compost and bioenergy.

- Japan’s Food Recycling Law (2001): Requires businesses to recycle surplus food into animal feed, fertilizers, and biofuel, achieving over 80% recycling rate.

- South Korea’s Mandatory Food Waste Recycling: Implements a pay-as-you-throw system with smart bins and recycles >95% of food waste into feed, compost, or energy.

- China’s “Clean Plate Campaign” (2020): Promotes awareness against over-ordering and over-serving, encouraging responsible consumption.

- Innovative Technologies Worldwide:

- Hermetic Storage (Africa): Airtight storage bags and silos (e.g., Purdue Improved Crop Storage – PICS bags) significantly reduce post-harvest grain losses.

- IoT and AI in Europe & US: Smart sensors, blockchain traceability, and predictive analytics optimize storage, transport, and distribution.

- Cold Chain Models (Netherlands, Denmark): Integrated farm-to-retail cold chains preserve perishables, reducing losses and ensuring nutritional quality.

|

Benefits of Increase in Grain Storage Infrastructure

- Food & Nutritional Security: Ensures buffer stocks under NFSA (2013) for ~67% of the population, strengthens food security up to Panchayat/village level, and prevents fungal contamination, pests, and aflatoxins.

- Reduction in Post-Harvest Losses: Expanding scientific storage capacity cuts current losses of ~10–15%, enabling farmers to earn better prices and reducing wastage-driven emissions (supporting SDG 13 – Climate Action).

- Price Stabilisation & Farmer Empowerment: Protects farmers from distress sales, shields consumers from inflation, and allows farmers to choose markets, access agri-inputs locally, diversify income, and realise better value.

- Lower Handling & Transportation Costs: With PACS as procurement centers and Fair Price Shops (FPS), grains need not be transported multiple times, reducing logistics costs and leakages.

- Efficient & Resilient Supply Chain: Decentralised storage bridges the gap between farms and consumers, ensuring a stable and transparent grain distribution system.

- Disaster Preparedness: Maintains reserve stocks for emergencies such as droughts, floods, or pandemics, strengthening supply resilience.

- Regional Balance & Strategic Importance: Reduces state-level disparities, improves last-mile connectivity, and enhances national food sovereignty against climate change and population growth.

Foodgrain Storage in India- Key Dimensions and Challenges

- Socio-Economic Dimensions:

- Food Injustice and Hunger Paradox: Even as India harvested a record ~354 MMT of foodgrains in 2024–25, millions remain food-insecure. Post-harvest losses prevent food from reaching vulnerable groups, widening the gap between availability and access.

- Impact on Vulnerable Groups: Malnutrition continues to affect women, children, and marginalised communities most severely. Nutrient losses in perishables like milk, pulses, fruits, and vegetables worsen the crisis of hidden hunger.

- Global Hunger Index (2024): India ranked 111th out of 125 countries, indicating serious levels of hunger. Indicators like stunting (low height-for-age) and wasting (low weight-for-height) reflect deep-rooted nutrition shortfalls aggravated by food losses.

- Social Inequality: While urban middle classes waste food at consumer level, poor households suffer ration shortages, exposing inequities in distribution and consumption.

- Environmental Dimensions:

- Wasted Natural Resources: Post-harvest losses translate into wastage of water, land, and energy. Globally, wasted food consumes 250 km³ of freshwater annually, and in India alone, losses equal the annual drinking water needs of 100 million people.

- Soil and Water Degradation: Dumped food in landfills produces methane emissions and toxic leachate, contaminating groundwater and degrading soils.

- Climate Burden: Food waste contributes 8–10% of global GHG emissions, more than the aviation and shipping sectors combined. India’s own food losses emit over 33 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent annually.

- Economic Dimensions:

- Direct Monetary Impact: NABCONS (2022) estimated annual post-harvest losses at ₹1.5 trillion, equivalent to 3.7% of agri-GDP.

- Farmers’ Incomes: Spoilage reduces marketable surplus, forcing distress sales and limiting investment capacity in seeds, fertilizers, and irrigation.

- Food Inflation: Loss-induced supply shortages raise the prices of vegetables, pulses, and onions, fuelling inflationary volatility and burdening households.

- Macroeconomic Strain: Public spending on irrigation, subsidies, power, and procurement is wasted when food spoils, inflating fiscal costs without delivering social benefits.

- Weak cold chain and storage systems undermine supply chain efficiency and cause feed/fodder spoilage, thereby affecting the economics of animal rearing.

- Persistent Bottlenecks in Foodgrain Storage:

- Inadequate Storage Capacity: Despite growing harvests, current capacity covers less than 60% of demand, leading to excessive dependence on FCI warehouses.

- Regional Imbalances: Southern states maintain 90%+ capacity, whereas northern states function with less than 50%, creating logistics bottlenecks and wastage.

- Post-Harvest Losses: Around 10–15% of grains are lost annually to pests, moisture, and unscientific storage, reducing both national reserves and farmer incomes.

- Weak Cold Chain Infrastructure: India’s 8,815 cold storages (402.18 LMT capacity as of June 2025) are inadequate to preserve perishable, nutrient-rich foods, worsening hidden hunger.

- Technological Gaps: Limited adoption of steel silos, hermetic storage, and IoT-based monitoring keeps the system reliant on outdated godowns.

- Governance Issues: Overlapping roles of FCI, state agencies, and cooperatives create coordination delays, while leakages and diversion erode efficiency.

- Climate Risks: Increasing floods, heatwaves, and rainfall extremes compromise open storage (CAP), exposing stocks to spoilage and contamination.

Way Forward

- Modern and Climate-Resilient Infrastructure: Upgrading storage and cold chain facilities is essential.

- Investments in pre-cooling units, refrigerated transport, modern warehouses, and mechanised silos under schemes like Pradhan Mantri Kisan SAMPADA Yojana (PMKSY) can significantly reduce grain and perishable losses.

- Expanding solar-powered cold storages and low-cost cooling chambers will particularly help smallholder farmers.

- Upstream and Downstream Interventions: These interventions reduce food loss across the supply chain, improve quality, ensure efficient delivery, and strengthen food and nutritional security.

- Upstream: Mechanisation in harvesting reduces spillage; improved post-harvest handling (drying, threshing, grading) prevents damage; and adoption of climate-resilient seeds minimises losses from extreme weather.

- Downstream: Expanding cold chains from farm-gate to retail, creating food processing parks for surplus absorption, and strengthening logistics through reefer vans and warehouses can bridge farm-to-market gaps efficiently.

- Convergence of Schemes: India needs synergy between the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF), PMKSY, and the World’s Largest Grain Storage Plan.

- Together, these can create a farm-to-fork ecosystem: PACS collects produce, AIF funds storage, PMKSY adds processing capacity, and the Public Distribution System (PDS) ensures last-mile delivery.

- Digital and Smart Solutions: Technology must be mainstreamed. Artificial Intelligence (AI) can forecast demand and optimise storage; Internet of Things (IoT) sensors can monitor grain quality in real time; and blockchain can bring transparency in procurement and distribution.

- Digital dashboards can track progress towards SDG 12.3 (halving food waste by 2030).

- Strengthening Cooperative and Community Institutions: Reviving non-functional PACS and linking them with storage, procurement, and retail functions at the Panchayat level will reduce transportation costs and empower farmers.

- Integration with Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) can strengthen community-level aggregation and marketing.

- Sustainable and Circular Practices: Promoting hermetic storage reduces pest and fungal damage, while adopting circular economy models—converting surplus food into compost, cattle feed, or bioenergy—prevents landfill accumulation and reduces methane emissions.

- Stakeholder Partnerships: Effective stakeholder partnerships ensure coordinated action across government, private sector, civil society, and consumers to minimise food loss and enhance food security.

- Government: Must integrate food loss reduction into climate and food security policies, ensure scheme convergence, and support innovation.

- Private sector: Should invest in storage, cold chains, logistics, and food-tech solutions.

- Civil society & NGOs: Can expand food banks, run awareness campaigns, and support redistribution networks.

- Consumers: Have a critical role in reducing plate-level waste through responsible consumption campaigns like “Save Food, Share Food.”

- Linking Food Security with Climate Action: Reducing food loss provides a double dividend– it improves availability for vulnerable populations while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- This strengthens India’s food security and advances its climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Conclusion

- Reducing food loss and waste advances SDG 12.3 (Responsible Consumption), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), while upholding constitutional values [Article 39(b) – equitable resource distribution; Article 47 – nutrition & public health], ensuring an inclusive, sustainable, and food-secure India.

![]() 29 Sep 2025

29 Sep 2025

Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF): Launched in 2020 to finance post-harvest and farm-gate infrastructure with interest subvention and credit guarantee.

Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF): Launched in 2020 to finance post-harvest and farm-gate infrastructure with interest subvention and credit guarantee.