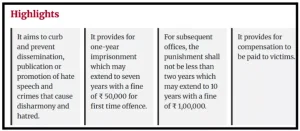

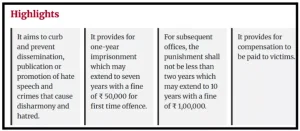

The Karnataka Hate Speech and Hate Crimes (Prevention) Bill, 2025), is India’s first state-level law to specifically address hate speech.

Key Provisions of the Karnataka Hate Speech and Hate Crimes (Prevention) Bill, 2025

- Expansive Definition: An act or expression on the basis of religion, race, caste or community, sex, gender, sexual orientation, place of birth, residence, language, disability or tribe has been categorised as “hate speech” and “hate crime”.

Hate Speech: Any form of expression (spoken, written, electronic, or visual) made publicly with the deliberate aim to cause injury, enmity, hatred, or ill-will against any group.

Hate Speech: Any form of expression (spoken, written, electronic, or visual) made publicly with the deliberate aim to cause injury, enmity, hatred, or ill-will against any group.

- Basis: Targets groups based on identity markers such as religion, race, caste, or gender.

- Hate Crime: The communication, publishing, or circulation of hate speech, or any act of promoting, propagating, inciting, or attempting such speech.

- Goal: To cause disharmony, enmity, hatred, or ill-will against any person (dead or alive), group, or organization.

- Drastic Penalties: Offences are designated as cognisable (allowing arrest without warrant) and non-bailable.

- Punishment starts with a minimum of one year and can extend up to 10 years imprisonment along with a fine of up to ₹1 lakh for repeat offenders.

- Victim Support: A provision is included for providing adequate compensation to victims, calculated based on the severity of the harm caused by the hate crime.

- Digital Takedown Power: State authorities are granted the power to directly instruct social media companies and service providers to block or remove hateful content disseminated through their platforms.

- Organisational Accountability: The Bill introduces the concept of collective liability, making individuals in positions of control or responsibility within an organisation liable for offenses linked to their group’s activities.

- Exemptions: The Bill’s provisions do not cover any textbooks, pamphlets, papers, writings, drawings, paintings, representation or figures in the electronic media or whose publication is done in the interest of the public good.

- This includes science, literature, art, learning or are used for “bona fide” heritage or religious purposes.

PWOnlyIAS Extra Edge:

Merits of the Karnataka Hate Speech and Hate Crimes (Prevention) Bill, 2025

- Addresses Enforcement Gaps: It attempts to fix the current legislative void by creating a specific law, moving beyond the limitations of existing, broad Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) sections (like 196 and 299) which have historically led to low conviction rates.

- The conviction rate under existing laws (like former Indian Penal Code (IPC) 153A/295A, now BNS) is remarkably low, remaining below 21%.

- Victim-Centric: The law introduces victim compensation and proposes dedicated investigative machinery, adopting a progressive approach focused on restorative justice.

- Responds to Real Incidents: The legislation is a direct response to tangible threats and social disharmony, including coastal Karnataka violence and the damage caused by widespread online hate campaigns.

Arising Concerns with the Bill

- Overbroad Definition: The Bill uses unclear words like “ill-will” and “psychological harm,” which can easily be misused to target criticism or satire.

- Such vagueness threatens Articles 14, 19(1)(a), and 21, going against the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shreya Singhal (2015).

- Its loose language and strict punishments repeat the pattern seen in Sedition and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, where broad powers were used to suppress dissent and political opposition.

- Chilling Effect Despite Exemptions: Although the Bill lists exemptions (for art, science, etc.), the punishing nature of the criminal justice system (cognisable, non-bailable offences) means the process itself (arrest and detention) becomes the punishment. These exceptions therefore offer little practical comfort against the chilling effect on legitimate speech.

- Federalism and Jurisdictional Overlap: The state law’s intrusion into the criminal law sphere (a Concurrent List subject) risks a serious Centre-State conflict with the recently enacted Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and the Central IT Rules, 2021.

- Disproportionate Penalties: With provisions for non-bailable offences and jail terms up to 10 years, the severity of the punishment for mere words is disproportionate.

- This fails the strict proportionality test under Article 21, as re-emphasised in Kaushal Kishor (2023).

- Executive Overreach in Censorship: Allowing Deputy Superintendents of Police (DSPs) and Executive Magistrates to issue direct content-takedown orders without court approval removes vital safeguards, contradicting principles noted in Amish Devgan Case (2020).

- This power also risks conflict with the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and bypasses the Information Technology (IT) Rules, 2021, including mandatory due-diligence requirements for social media platforms.

- Collective Liability: The law holds leaders responsible for the speech of their members, which seriously risks infringing on Article 19(1)(b), the freedom of association for political, social, and religious groups.

- Missing Threshold of Incitement: The Bill lacks the constitutional requirement of a nexus to “imminent violence,” setting a dangerously low threshold for restricting speech, thus contradicting the strict guidelines laid down in Pravasi Bhalai (2014).

Way Forward

To make the law effective and constitutionally sound, a measured strategy is essential:

- Legislative Scrutiny and Review: The Bill must be referred to a Select or Joint Committee for thorough public consultation, ensuring the inclusion of legal experts and civil society members to refine its provisions.

- Adopt Precise, Constitutional Definitions: The state must adopt the Supreme Court’s 2021 hate-speech guidelines and the Law Commission’s 267th Report recommendations to craft a definition that is narrowly focused on incitement to violence, not vague subjective harms.

- Mandate Judicial Oversight: All executive actions related to content takedown orders must be made subject to prior approval by a Judicial Magistrate (e.g., within 24 hours).

- This safeguards due process and prevents abuse of power.

- Decriminalise Minor Offences: The law should de-criminalise first-time or minor speech offenses, reserving high prison terms only for cases involving severe incitement or organised crime.

- Minor offenses should be addressed with civil penalties and mandatory counselling.

- Promote Counter-Speech: The State must invest in media literacy and education to equip citizens with critical thinking skills.

- The democratic solution is to actively promote counter-narratives and good speech rather than relying solely on censorship.

Should Other States Adopt a Karnataka-Style Hate Speech Bill?

- The issue of hate speech is a serious challenge across India. While other states must act, they should avoid replicating Karnataka’s risky model. The focus should be on better enforcement of existing laws, not creating new ones that are easily misused.

- Why the Karnataka Model Is Risky for Other States?

- The table below shows that the Bill offers minimal benefit while introducing significant legal dangers that would plague any state that adopts it:

| Aspect |

Existing National Laws (Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita – BNS & Information Technology Act – IT Act) |

What a Karnataka-Style Bill Adds |

Risk for Other States |

| Definition |

- No specific definition; restrictions guided by Supreme Court (SC) rule of incitement to imminent violence.

|

- Broad terms like “ill-will” and “disharmony.”

|

- Increases legal vagueness and the potential for political misuse.

|

| Online Takedowns |

- Central Information Technology Act (IT Act) Section 69A and 2021 Rules require procedural steps (Government Access Committee – GAC oversight).

|

- Direct takedown orders by local police/magistrates without judicial approval.

|

- Bypasses Central safeguards, invites Executive Overreach, and encourages over-censorship.

|

| Penalties |

- Up to 3–7 years for most enmity offences.

|

- Up to 10 years, non-bailable, and includes collective liability for organizations.

|

- Punishments are disproportionate and create a severe chilling effect on legitimate speech.

|

| Conviction Rates |

- Low, at about 20%, primarily due to poor investigation and faulty First Information Reports (FIRs).

|

- Same police force, new label.

|

- New laws do not fix poor implementation or lack of police training.

|

| Bias Violence |

- Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) Section 103(2) aggravates penalties for hate-motivated murder.

|

- Adds a new “hate crime” tag and includes victim compensation.

|

- Victim compensation is useful, but it can be implemented through existing state schemes without needing a new, controversial law.

|

Better Alternatives- Strengthening Existing System:

Instead of creating a new tool prone to abuse, states should focus on strengthening the implementation of current Central laws:

- Police Reform and Training:

- Mandatory Suo Motu FIRs: Strictly enforce the Supreme Court (SC) directive requiring police to register cases automatically (suo motu – on their own motion) upon noticing hate speech, without waiting for formal complaints.

- Dedicated Wings: Establish specialized communal offence wings within police forces for trained investigation.

- Judicial Efficiency:

- Fast-Track Courts: Establish special courts dedicated to swiftly trying cases filed under BNS enmity sections (like the Kerala model for certain offences).

- Victim Support:

- Enhance Compensation: Immediately improve and expand existing state victim compensation schemes to address harm caused by hate violence.

- Social and Digital Prevention:

- Boost Media Literacy: Launch large-scale campaigns and integrate digital literacy into education to equip citizens against misinformation and hate.

- Promote Counter-Speech: Actively encourage and support civil society efforts to promote reasoned dialogue and constructive counter-narratives.

|

About Hate Speech

- Definition: The UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech defines hate speech as “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.”

- However, to date there is no universal definition of hate speech under international human rights law. The concept is still under discussion, especially in relation to freedom of opinion and expression, non-discrimination and equality.

- Legal & Constitutional Provisions: Hate speech has not been defined in any law in India.

- The efforts to curb hate speech are rooted in India’s constitutional limitations and its criminal statutes.

- These sections are primarily meant to maintain “public order”, rather than to penalise hate speech as a distinct category.

- Constitutional Basis: Article 19(1)(a): Guarantees the vital right to freedom of speech and expression.

- Article 19(2): Allows the government to impose reasonable restrictions on this right in the interest of, most notably, public order and to prevent incitement to an offence.

- This Article is the foundation for all hate speech restrictions.

- Indian Criminal Laws (BNS/IPC): Section 196 of BNS (Old IPC 153A) punishes promoting enmity or hatred between different groups based on identity factors.

- According to National Crime Records Bureau data cited in previous reports, the conviction rate for Section 153A in 2020 was merely 20.2%.

- Section 299 of BNS (Old IPC 295A): Targets deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage the religious feelings of any group by insulting their beliefs.

- Section 505 of BNS (Old IPC 505): Addresses statements or rumours that cause public mischief or create ill-will/hatred between different classes.

- Other Laws: The Representation of People Act (RPA), 1951, includes provisions to penalise the use of hatred or enmity in election campaigning.

About Hate Crime

- Hate crime is a criminal act (like assault, murder, or vandalism) that is specifically motivated by the offender’s bias or prejudice against the victim’s actual or perceived membership in a specific social group.

- Key Elements: A hate crime requires two components:

- Base Offense: The act must always be a pre-existing crime under the general criminal code.

- Bias Motivation: The motive is based on the victim’s identity (e.g., religion, caste, race, sexual orientation). This bias acts as an aggravating factor that allows for a harsher sentence than for the same crime committed without such prejudice.

- Legal Status in India: India lacks a dedicated, comprehensive law explicitly defining and classifying “Hate Crime.”

- BNS (Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023): The BNS is a significant step forward, as it explicitly recognizes bias motive as an aggravating factor for serious offenses like murder (e.g., Section 103(2)), allowing for enhanced punishment.

- Historical Approach: Previously, crimes motivated by hate were generally prosecuted under sections designed for communal disharmony (e.g., former IPC 153A/295A).

- Challenge: The main legal hurdle remains the difficulty in getting police to officially identify and register the bias motive at the initial FIR stage.

- Hate Crime vs. Hate Speech: It’s essential to distinguish between the two:

- Hate Crime is an act of violence or property damage that enhances the penalty for a physical crime.

- Hate Speech is a form of expression (words, images) that criminalizes the speech itself if it constitutes incitement to hatred.

|

Key Judgements Related to Hate Speech in India

The Supreme Court has acted as a key arbiter, providing legal clarity on restrictions:

- Ramji Lal Modi v. State of UP (1957): Affirmed that restrictions on speech that deliberately outrage religious feelings are valid because such acts have a direct, close relationship to disrupting public order.

- Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan v. Union of India (2014): The Court highlighted the need for a focused law and directed the Law Commission to suggest measures, including a clear legal definition for hate speech.

- Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015): This landmark ruling scrapped Section 66A of the IT Act due to its vagueness and potential for misuse to silence protected speech. It cemented that only speech amounting to direct incitement can be restricted under Article 19(2).

- Shaheen Abdulla v. Union of India (2022): Acknowledging the dangerous rise in hate speech, the Court mandated that police and authorities should take immediate, automatic action (suo motu) against offenders without waiting for formal complaints.

- Kaushal Kishor v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2023): Reaffirmed the State’s constitutional obligation to protect citizens’ rights against harm from all sources, even non-state actors, while also emphasising the need for proportional restrictions on speech.

India’s Historical Legislative Attempts to Curb Hate Speech

- Viswanathan Committee (2015): Formed to address the legal vacuum after Section 66A was struck down, this expert panel proposed adding specific clauses to the IPC.

- It suggested new Sections 153C(b) and 505A to penalise incitement to offences targeting groups based on a wide list of characteristics (e.g., religion, gender identity, language, disability) with up to two years’ imprisonment.

- Bezbaruah Committee (2014): Established following attacks on people from the North-Eastern States, this committee recommended stronger anti-racial discrimination provisions.

- It proposed amending the IPC to include offences like promoting acts prejudicial to human dignity (with up to five years’ jail) and insulting a particular race (with up to three years’ jail).

- Law Commission of India: The 267th Report (2017) strongly recommended inserting new Sections 153C and 505A into the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

- As per the 267th Law Commission Report (2017), hate speech is an expression that is primarily an incitement to hatred against a group of persons defined by their identity, such as religion, gender, or sexual orientation.

- The goal was to specifically criminalise incitement to hatred and the act of provoking violence, thus providing distinct legal tools separate from general public order provisions.

- Its function is to delegitimise and marginalise group members, potentially leading to fear, discrimination, and violence.

- Determining whether speech constitutes an illegal offense relies heavily on the context and the intent to provoke unlawful action.

- Private Member’s Bill (2022): The Hate Speech and Hate Crimes (Prevention) Bill, 2022, was presented in the Rajya Sabha. It aimed to provide a statutory definition, framing hate speech as any expression that incites, promotes, or spreads discrimination, hatred, or violence.

- However, this parliamentary initiative did not become law.

Need to Curb Hate Speech

- Protecting Human Dignity: Hate speech fundamentally attacks the dignity and equality of targeted groups (Article 14 and 21), stripping them of their self-worth and social acceptance.

- Preserving Social Fabric: It acts as a dangerous catalyst for communal violence, discrimination, and deep societal fragmentation, threatening India’s commitment to secularism and pluralism.

- Upholding Public Order: Unchecked inflammatory speech often leads to real-world clashes and a breakdown of law and order, justifying the State’s intervention as per constitutional mandates.

Challenges of Hate Speech

- Legal and Constitutional Hurdles:

- Vague Legal Definition: India lacks a precise, statutory definition of hate speech. Enforcement relies on broad colonial-era laws (BNS/IPC) meant for “public order,” leading to subjective application and misuse.

- Failure of Deterrence: Existing BNS provisions (Sections 196, 299) are ineffective. Despite frequent arrests, the conviction rate is extremely low (around 20%), demonstrating a systemic failure to deter offenders.

- Chilling Effect: The threat of prosecution under vague laws (like UAPA/Sedition) is often used to suppress political dissent and criticism, chilling the fundamental right to freedom of expression (Article 19(1)(a)).

- Digital and Enforcement Deficiencies:

- Social Media Amplification: Digital platforms act as amplifiers, allowing hateful content to spread virally and instantaneously. This fast, wide dissemination often links directly to offline communal violence and mob action.

- Enforcement Bias: There is a persistent lack of political and institutional will to take suo motu (automatic) action against hate speech, especially when delivered by high-profile figures.

- Anonymity and Jurisdiction: The ability of offenders to post anonymously and from servers outside India creates massive problems of tracing, investigation, and jurisdiction for local police.

- Societal and Political Risks:

- Political Normalization: Political figures increasingly use divisive rhetoric as a tool for electoral polarization, which in turn normalizes hate within the public discourse.

- Targeted Impact: Hate speech disproportionately targets marginalized communities (religious minorities, Dalits, LGBTQ+), leading to their dehumanization, fear, and increased vulnerability to violence.

Global Initiatives & Best Practices to Curb Hate Speech

- International Frameworks (UN Guidance):

- UN Strategy & Plan of Action (2019): A UN-wide commitment to address hate speech by focusing on root causes (education) and advocacy, without limiting free speech itself.

- The Rabat Plan of Action (2012): Provides the key ethical threshold by defining a Six-Part Test (Context, Intent, Likelihood, Content and Form, Extent of Dissemination, and Likelihood of Harm) to distinguish protected speech from prohibited incitement.

- Legislative Accountability (EU Model):

-

- EU Digital Services Act (DSA): It mandates that Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) must conduct annual risk assessments and implement risk mitigation measures against illegal content and systemic harm.

- Mandates high transparency and provides users with the right to contest moderation decisions (due process).

- Non-compliance risks massive fines (up to 6% of global turnover).

- Germany’s NetzDG (Network Enforcement Act): Pioneered platform liability, mandating the removal of “clearly illegal” content within 24 hours or facing substantial fines.

|

Way Forward

- Legislative Precision and Clarity:

- Enact a Tailored Definition: Any new law, whether at the state or central level, must adopt a definition that is focused on incitement to violence or hostility and is narrowly constructed.

- This prevents the prosecution of legitimate advocacy and ensures the law is compliant with Article 19(2) standards.

- Implement Proportionality in Penalties: The quantum of punishment should be graded based on the severity and impact of the offense.

- Extremely harsh penalties should be reserved for severe, violent incitement, while lesser offenses are treated with proportional sanctions.

- Institutional Strengthening and Judicial Scrutiny:

- Ensure Judicial Oversight: Mandatory provisions must be added to ensure that the police’s power to issue takedown orders, arrest, or take preventive action is subject to prior approval by a Judicial Magistrate.

- This is a necessary check against Executive Overreach.

- Enhance Enforcement Capabilities: The government should create dedicated anti-hate crime units and establish fast-track legal procedures to investigate and prosecute these cases efficiently, thereby raising the currently low conviction rate.

- Social and Educational Counter-Measures:

-

- Boost Media Literacy: The State must invest in large-scale public campaigns and school curricula to build digital and media literacy.

- This empowers citizens to critically evaluate and reject misinformation and hateful propaganda.

- Promote Counter-Speech: Instead of solely relying on censorship, the government and civil society should actively encourage and amplify constructive counter-narratives.

- The most effective democratic answer to malicious speech is often the deployment of more reasoned, good speech in the public domain.

Conclusion

The Karnataka Bill has noble intent, but its vague definitions and draconian penalties violate proportionality and threaten dissent. True harmony requires judicial oversight and precise laws that focus on incitement to violence, not just offense. A sustainable response requires precise laws, judicial oversight, and counter-speech, ensuring human dignity without compromising constitutional freedoms.

![]() 12 Dec 2025

12 Dec 2025

Hate Speech: Any form of expression (spoken, written, electronic, or visual) made publicly with the deliberate aim to cause injury, enmity, hatred, or ill-will against any group.

Hate Speech: Any form of expression (spoken, written, electronic, or visual) made publicly with the deliberate aim to cause injury, enmity, hatred, or ill-will against any group.