At the 2025 Global Conference on Climate and Health (Belém, Brazil), delegates from 90 countries came together to shape the Belém Health Action Plan.

About Global Conference on Climate and Health

- Venue: International Convention Center, Brasília, Brazil.

- Hosted by: Government of Brazil, World Health Organization (WHO), and the Panamerican Health Organization (PAHO)

- Significance: Served as the annual in-person meeting of ATACH (Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health).

- Main Outcomes:

- Inputs for drafting the Belém Health Action Plan (to be launched at COP30).

- Defined countries’ commitments under ATACH to support the Plan.

- Established health as a core pillar of global climate action.

- Scientific deliverables to guide implementation of the Plan.

- India’s absence: India was not officially represented, a missed opportunity to showcase its developmental model despite being highly vulnerable to climate-health risks.

|

About Belem Health Action Plan

- AIM: The plan aims to create a global roadmap that integrates health priorities within the broader climate agenda.

- Cross-Cutting Priorities:

- Health equity and climate justice.

- Stronger governance with social participation (women, youth, Indigenous peoples, vulnerable groups).

- Action Lines:

- Surveillance & Early Warning: Climate-informed health monitoring, real-time data, and strategic stockpiles of medicines and vaccines.

- Evidence-Based Policy & Capacity Building: Training health workers, integrating climate content into curricula, gender-responsive adaptation, and community resilience.

- Innovation & Production: Climate-resilient infrastructure, renewable energy in health facilities, sustainable supply chains, and just transitions for vulnerable groups.

- Why does India’s experience matter?

- These programmes show that non-health interventions can generate substantial health co-benefits while addressing climate challenges.

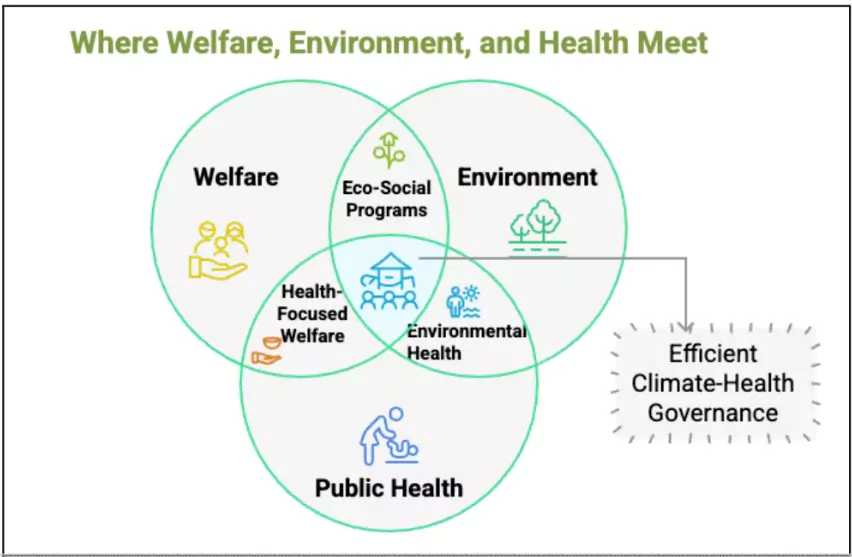

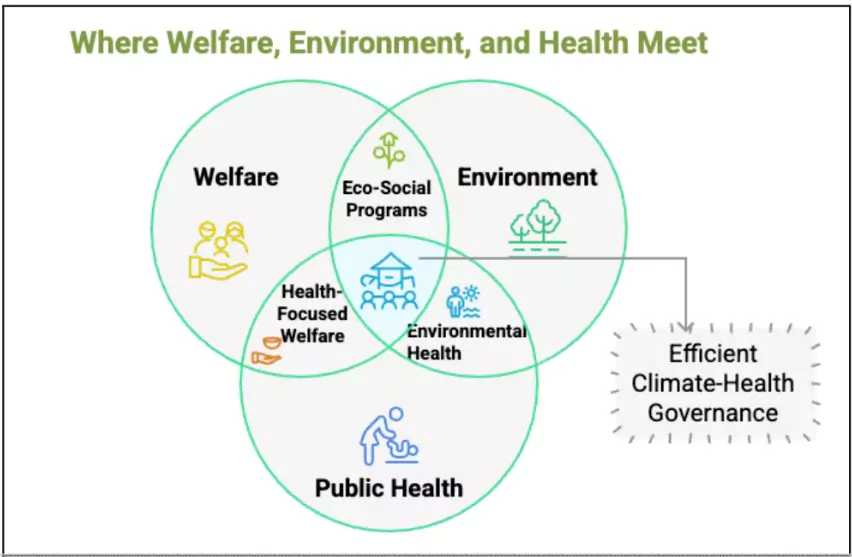

- They provide a practical governance template where welfare, environment, and public health intersect.

- India’s welfare programmes, though not designed as climate policies, have created remarkable health and climate co-benefits, offering lessons for integrated climate-health governance globally.

Lessons from India in Climate-Health Governance

- Political Leadership Ensures Policy Convergence: High-level involvement drives coordination across ministries and accelerates implementation.

- Example: Direct Prime Ministerial push for Swachh Bharat and PMUY brought multiple departments together and delivered nationwide results.

- Community Engagement Builds Ownership: Cultural values and grassroots participation make policies more relatable and sustainable.

- Example: Swachh Bharat invoked Gandhi’s vision of cleanliness, while PM Poshan relied on Parent-Teacher Associations for community support.

- Leveraging Existing Institutions Enhances Delivery: Using established networks avoids duplication and ensures last-mile reach.

Example: ASHA workers, Panchayats, and Self-Help Groups became effective channels for implementing welfare programmes.

Example: ASHA workers, Panchayats, and Self-Help Groups became effective channels for implementing welfare programmes.

- Scalable Models for the Global South: India’s welfare-based interventions demonstrate how low-cost policies can achieve health, climate, and development goals together.

- Example: Schemes like PM Poshan (Nutrition + Climate-resilient crops) and PMUY (Clean energy + Health gains) show pathways that other developing nations can adopt to align with SDG-3 (Health), SDG-7 (Clean Energy), and SDG-13 (Climate Action).

India’s Welfare Programmes and their Climate–Health Co-Benefits

Though none of these schemes began as climate initiatives, they have generated significant environmental gains alongside health improvements.

- Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY): By replacing biomass with LPG for cooking, the scheme reduced household air pollution and respiratory ailments while simultaneously cutting carbon emissions.

- PM Poshan (Mid-Day Meal Scheme): The programme tackles malnutrition, integrates millets into school meals which supports child health and builds climate-resilient food systems (aligned with 2023 UN International Year of Millets).

- Swachh Bharat Abhiyan: The nationwide sanitation mission improved hygiene, reduced diarrhoeal disease, and enhanced dignity, while also advancing environmental goals through cleaner water sources and safer waste management.

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA): By ensuring wage employment, the scheme enhanced rural livelihoods and simultaneously funded ecological works such as afforestation, watershed management, and soil conservation, strengthening community climate resilience.

Constitutional and Ethical Dimensions

- Directive Principles of State Policy: Article 47 places a duty on the State to improve public health, while Article 48A directs it to protect and improve the environment.

- Fundamental Rights Linkage: Article 21 (Right to Life) has been judicially expanded by the Supreme Court to include the right to a clean environment and health, making climate-health governance a constitutional obligation.

- Fundamental Duties of Citizens: Article 51A(g) obligates every citizen to protect and improve the natural environment, creating an ethical and constitutional basis for community participation.

- Ethical Imperative of Intergenerational Equity: Integrating climate and health ensures justice for future generations, preventing them from bearing disproportionate burdens of today’s inaction.

- Gandhian Trusteeship and Social Justice: Welfare schemes that link health and climate reflect Gandhian principles of trusteeship, where resources are managed for the collective good, especially the most vulnerable.

|

Challenges of Integrating Health and Climate through Welfare Policies

- Administrative Silos: Ministries and departments work independently, which restricts intersectoral cooperation between health, energy, agriculture, and environment.

- Example: India’s Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) process does not mandate Health Impact Assessments (HIAs), meaning health outcomes of climate policies and projects are rarely evaluated systematically.

- Economic Barriers: Affordability issues and competing business interests reduce the long-term impact of welfare-linked climate policies.

- Example: High LPG refill costs under PMUY discourage sustained usage, as oil marketing priorities often outweigh beneficiary needs.

- Social and Cultural Resistance: Deep-rooted practices, gender norms, and behavioural inertia hinder adoption of cleaner and healthier alternatives.

- Example: Despite LPG distribution, many households continue to use biomass due to cooking preferences and cultural habits.

- Equity Concerns: Marginalised groups struggle with access and benefit delivery, reinforcing inequalities in health and climate resilience.

- Example: Tribal and remote communities often face gaps in sanitation coverage, nutrition schemes, and clean energy access.

- Fifth round of the National Family and Health Survey (NFHS-5) report showed that 30% of households still have not used an improved sanitation facility, and it is considerably higher in rural areas (35%)

Economic Costs of Inaction

- High Burden of Climate-Linked Diseases: WHO projects that climate change could cause 250,000 additional deaths annually between 2030–2050 due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea, and heat stress.

- GDP Losses from Pollution-Linked Illnesses: The World Bank estimates that India loses around 1.7% of GDP annually due to health costs from air pollution, showing that preventive measures are more cost-effective than reactive spending.

- Productivity Losses due to Heat Stress: The Lancet Countdown (2022) reported that India lost about 167.2 billion potential labour hours in 2021 because of heat exposure, mainly affecting outdoor workers in agriculture and construction.

- Impact on Livelihoods and Agriculture: Erratic monsoons and rising temperatures reduce crop yields, lowering farm incomes and threatening food security.

- This leads to indirect health impacts like malnutrition and higher economic vulnerability.

|

Way Forward for India’s Climate-Health Governance

- Strategic Prioritisation by Political Leaders: Framing climate action as an immediate health and welfare issue generates stronger political will and public acceptance.

- Example: PMUY gained traction by being projected as women’s empowerment and a health intervention, not just an energy reform.

- Procedural Integration Across Ministries: Embedding health considerations into all climate-relevant policies ensures intersectoral convergence.

- Example: Just as Environmental Impact Assessments are mandated for major projects, Health Impact Assessments can be made compulsory for policies in energy, transport, and urban planning.

- Participatory Implementation at the Community Level: Mobilising communities through local institutions builds ownership and sustainability of climate-health policies.

- Example: Involving ASHA workers and Panchayats in awareness campaigns can make connections between climate action and everyday health outcomes more relatable.

- Outcome-Based Monitoring Mechanisms: Measuring results in terms of health improvements rather than only outputs ensures accountability and effectiveness.

- Example: Instead of counting LPG cylinders distributed, monitoring should track actual reduction in respiratory illnesses and adoption rates of clean fuel.

- International Leadership and Knowledge Sharing: India can showcase its welfare-linked climate-health successes to influence global frameworks.

- Example: Lessons from Poshan, Swachh Bharat, and MNREGA can be shared through platforms like COP30 to guide the Belém Health Action Plan for the Global South.

- Scaling Heat Action Plans: India can replicate the Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan (2013) which is South Asia’s first climate-health early warning system –across vulnerable regions.

- Such plans integrate early warning, medical preparedness, and community awareness, reducing mortality and productivity losses from heatwaves.

Conclusion

India’s experience shows that welfare-led, intersectoral governance creates win-win solutions for climate and health. By embedding health in climate policies, leveraging existing institutions, and ensuring equity, India can evolve a model of health-anchored climate governance that balances development, environment, and well-being.

![]() 22 Sep 2025

22 Sep 2025

Example: ASHA workers, Panchayats, and Self-Help Groups became effective channels for implementing welfare programmes.

Example: ASHA workers, Panchayats, and Self-Help Groups became effective channels for implementing welfare programmes.