Recently, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj organised PESA Mahotsav 2025 at Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, to commemorate the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996, reaffirming Gram Sabha authority, tribal self-governance, and cultural autonomy in Scheduled Areas.

About PESA Mahotsav

- National Platform for Tribal Self-Governance: PESA Mahotsav is a national-level initiative designed to strengthen the implementation of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996, while foregrounding tribal customs, institutions, and community decision-making as central to governance.

- Governance–Culture Convergence: The Mahotsav consciously integrates constitutional decentralisation with cultural expression, recognising that governance in Scheduled Areas must operate through customary norms and collective traditions, rather than uniform administrative models.

- Cooperative Federal Character: Participation of States with Fifth Schedule Areas enabled sharing of experiences and best practices, reinforcing cooperative federalism in tribal governance.

What Are Scheduled Areas?

- Schedule areas are defined under Article 244 (1) as the areas defined by the President of India.

- Scheduled areas are identified by the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution of India.

- Scheduled Areas are found in 10 States of India which have a predominant population of tribal communities.

Fifth And Sixth Schedules

- Fifth Schedule: The provision of the Fifth Schedule shall apply to the administration and control of the Scheduled Areas and Schedule Tribes in any State (other than the states of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram).

- Sixth Schedule: The provisions of the Sixth Schedule shall apply to the administration of the tribal areas in the State of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

|

Key Highlights of PESA Mahotsav 2025

- Official Mascot: The Mahotsav unveiled “Krishna Jinka” (Blackbuck) as the mascot, representing the agility, resilience, and deep-rooted spiritual connection of tribal communities with nature.

- Central Theme: “Utsav Lok Sanskriti Ka”

- Highlights culture as the foundation of governance in Scheduled Areas, rooting Gram Sabha authority in tribal traditions, indigenous knowledge, and customary resource management, rather than bureaucratic control.

- Cultural Assertion as Democratic Practice: Indigenous games such as Chakki Khel, Uppanna Barelu, Cholo, Puli Meka, Mallakhamba, Pithool, Gedi Doud, and Sikor were showcased, underlining that tribal culture is not ornamental but constitutive of self-governance.

- Digital and Institutional Innovations: The portal facilitates Gram Sabha–based planning, transparent tracking of funds, and monitoring of development activities, aligning digital governance with decentralised democracy.

- Outcome-Oriented Governance: Introduction of PESA Performance Indicators aim to assess real-world outcomes, such as compliance with Gram Sabha decisions, rather than mere procedural adherence.

- Training in Tribal Languages: Capacity-building material was released in Santhali, Gondi, Bhili, and Mundari, addressing linguistic exclusion that often limits effective participation.

- Cultural Documentation Initiatives: Electronic publications documenting tribal customs and practices institutionalise indigenous knowledge systems within governance frameworks.

- Policy Momentum: With Jharkhand’s approval, nine out of ten Fifth Schedule States have now framed PESA Rules, leaving Odisha as the only exception.

- Timed with the Mahotsav, Jharkhand approved its PESA Rules, advancing to nine states with framed rules.

About the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996

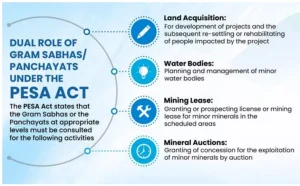

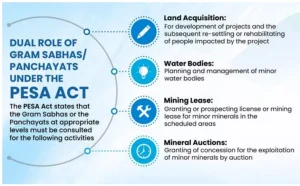

- Constitutional Extension of Decentralised Governance: The Act extends Part IX of the Constitution to Scheduled Areas under Article 243M(4)(b), with modifications respecting tribal social and cultural specificities.

- Primacy of the Gram Sabha: Unlike conventional Panchayati Raj Institutions, PESA places the Gram Sabha at the apex of governance, entrusting it with the protection of land, forests, water resources, culture, and social norms.

- Recognition of Customary Governance Systems: The Act legally validates customary laws, traditional dispute-resolution mechanisms, and collective ownership of community resources.

Need for the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996

- Exclusion under the Seventy-Third Constitutional Amendment Act, 1993: While the amendment institutionalised decentralised democracy, Scheduled Areas were excluded, acknowledging their distinct socio-cultural context but creating a governance gap.

- Recommendations of the Bhuria Committee (1995): The committee emphasised that decentralisation in tribal areas must be community-led, recommending constitutional recognition of Gram Sabha authority and resource control.

- Preventing Alienation and Exploitation: Prior to PESA, land acquisition and resource extraction occurred with minimal tribal consent, leading to displacement, conflict, and socio-economic marginalisation.

| A Comparative Analysis of General Panchayati Raj (Part IX) vs. Tribal Self-Rule (PESA Act): |

| Governance Feature |

General Panchayati Raj (73rd Amendment, 1992) |

PESA Act, 1996 (Fifth Schedule Areas) |

| Locus of Authority |

- Gram Panchayat Centric: Power is concentrated in the elected executive body (Gram Panchayat).

- The Gram Sabha is largely a recommendation body.

|

- Gram Sabha Centric: The Gram Sabha is the “Sovereign” unit.

- It is legally empowered to approve all development plans and identify beneficiaries before the Panchayat can act.

|

| Constitutional Intent |

- Administrative Convenience: Aimed at improving service delivery and local infrastructure development.

|

- Cultural Preservation: Aimed at protecting tribal identity, customary laws, and traditional management of “Land, Water, and Forest.”

|

| Land & Resource Rights |

- State Supremacy: The State can acquire land for “public purpose” with minimal local consultation. Minerals and forests are State-owned.

|

- Community Sovereignty: Mandatory Prior Informed Consent from the Gram Sabha is required for land acquisition, resettlement, and mining leases for minor minerals.

|

| Natural Resource Management |

- Regulated Access: Minor Forest Produce (MFP) and water bodies are usually managed by state line departments (e.g., Forest Dept).

|

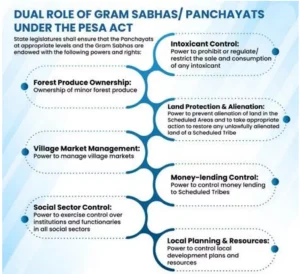

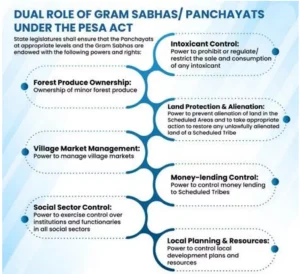

- Ownership Rights: Gram Sabhas have the absolute right of ownership over Minor Forest Produce (MFP) and management of local water bodies.

|

| Social & Moral Oversight |

- Limited Powers: Regulation of intoxicants or money lending depends entirely on specific State Legislations.

|

- Mandatory Powers: The Gram Sabha has the inherent power to prohibit or regulate the sale of liquor and to control usurious money lending to Scheduled Tribes.

|

| Reservation Policy |

- Proportional: Seats for SC/ST are reserved in proportion to their population at each level.

|

- Enhanced Protection: At least 50% of seats and 100% of Chairperson posts (Sarpanch/Adhyaksh) at all tiers are reserved for Scheduled Tribes.

|

| Conflict Resolution |

- Formal Judiciary: Disputes are settled through the police and formal court systems.

|

- Customary Laws: PESA recognizes the competence of the Gram Sabha to manage and resolve disputes according to traditional and customary methods.

|

| Legislative Overriding |

- State Subordination: State Legislatures have significant leeway to amend or dilute Panchayat powers.

|

- Non-Dilution Clause: State Laws cannot violate the mandatory provisions of PESA. It acts as a “Constitution within the Constitution” for tribal areas.

|

Significance of Implementing the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996

- Constitutional Integration and Democratic Inclusion: The PESA Act, 1996 operationalises Article 243M(4)(b) by extending Part IX (Panchayati Raj Institutions) to Fifth Schedule Areas without eroding tribal distinctiveness.

It integrates tribal governance into constitutional decentralisation, strengthening cooperative federalism and inclusive constitutionalism.

It integrates tribal governance into constitutional decentralisation, strengthening cooperative federalism and inclusive constitutionalism.- Example: The Ministry of Panchayati Raj data shows higher Gram Sabha participation in Telangana and Maharashtra after PESA rule notification.

- Participatory Democracy through Gram Sabha Supremacy: PESA replaces top-down governance with participatory democracy by vesting final decision-making authority in the Gram Sabha, ensuring development is consent-based rather than imposed.

- Example: Dantewada district, Chhattisgarh, where Gram Sabhas vetoed mining projects threatening sacred groves.

- Over one lakh tribal representatives trained by the Ministry of Panchayati Raj (2024–25) improved Gram Panchayat Development Plans.

- Environmental Sustainability and Resource Sovereignty: By recognising tribal communities as primary custodians of land, forests, and water, PESA promotes community-led conservation and prevents external over-extraction.

- Example: The Niyamgiri Judgment (2013) in Vedanta Limited versus Union of India upheld Gram Sabha authority over resource decisions affecting cultural and religious rights.

Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra, recorded improved forest management through community-controlled Minor Forest Produce systems.

Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra, recorded improved forest management through community-controlled Minor Forest Produce systems.

- Economic Self-Reliance and Local Revenue Generation: PESA enables village-level circular economies by transferring control over minor forest produce, minor minerals, and local markets to communities.

- Example: Vadagudem village, Telangana, where a Tribal Sand Mining Cooperative Society generates ₹40 lakh annually, financing education, healthcare, and agricultural credit.

- Social Reform and Women’s Leadership: The Act empowers Gram Sabhas to enforce community-driven social reform, while enabling substantive participation of women in governance and economic decision-making.

- Example: Mandla district, Madhya Pradesh, saw reductions in domestic violence following Gram Sabha-led liquor prohibition, while Jharkhand witnessed women-led Van Dhan Vikas Kendras managing forest produce value chains.

- Conflict Reduction and Internal Security Stabilisation: By addressing land alienation, displacement, and resource extraction without consent, PESA tackles structural drivers of Left-Wing Extremism and enhances state legitimacy in tribal regions.

- Example: Ministry of Home Affairs assessments note higher community cooperation in districts with functional Gram Sabhas, including Gadchiroli and Bastar.

- Rights-Based Development Planning and Last-Mile Delivery: PESA shifts development from scheme-centric implementation to rights-based planning through the Gram Panchayat Development Plan, improving targeting, convergence, and accountability.

- Example: In Scheduled Areas of Madhya Pradesh, Gram Sabha-approved plans improved coordination between Jal Jeevan Mission and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act works.

Issues and Challenges in PESA Implementation

- Weak Legal Enforceability and Diluted Consent: Although the PESA Act, 1996 is a Central legislation, its enforcement depends on State-specific rules, leading to uneven implementation.

- It applies only to Fifth Schedule Areas and does not cover tribal communities living outside Scheduled Areas.

- Example: Odisha continues with draft Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Rules, weakening Gram Sabha authority.

- Also, mandatory Gram Sabha consent is frequently bypassed using the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act, 1957 and the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.

- Example: The Xaxa Committee documented cases where consultation occurred only after land acquisition decisions.

- Institutional Fragmentation and Administrative Dominance: PESA vests authority in the Gram Sabha, while the Forest Rights Act, 2006 creates Community Forest Resource Committees, resulting in jurisdictional ambiguity.

- Example: In several forest areas, Forest Departments recognise Community Forest Resource Committees but bypass Gram Sabha resolutions, weakening community control.

- Fiscal and Administrative Constraints: Line departments such as Mining, Forest, and Excise resist devolution of revenue powers to Gram Sabhas.

- Example: Despite fund transfers to Panchayats, Gram Sabhas lack a dedicated financial stream, resulting in responsibility without revenue, as noted during Fifteenth Finance Commission consultations.

- Underutilisation of Fifth Schedule Safeguards: Under Paragraph 5 of the Fifth Schedule, Governors can modify or repeal laws harming tribal interests.

- Example: Even where State laws dilute Gram Sabha consent provisions, Governors have rarely exercised this power.

- Low Awareness and Legal Literacy at the Grassroots: Despite statutory empowerment, many Gram Sabhas remain unaware of their legal powers, making them vulnerable to administrative pressure.

- Example: Field-level assessments reveal that one-time trainings without tribal-language material limit effective assertion of Gram Sabha authority.

India’s Initiatives & Actions to Strengthen PESA

- Legislative Commitment to Tribal Self-Governance: Parliament enacted the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA) under Article 243M(4)(b) to constitutionally secure decentralisation and self-rule in tribal regions.

- States with Fifth Schedule Areas have been encouraged to frame State-specific PESA Rules, resulting in the notification of rules in nine out of ten States by 2025 (including the recent approval of Jharkhand PESA Rules, 2025).

- Executive Measures for Capacity and Accountability: The Ministry of Panchayati Raj (MoPR) has institutionalised implementation through a dedicated PESA Cell, staffed with experts in Law, Social Sciences, and Public Finance to provide policy guidance.

- Massive Training Outreach: Large-scale Master Trainer Programmes (2024–25) have trained over one lakh elected representatives and officials, significantly strengthening grassroots administrative capacity.

- Mainstreaming Development: Integration of PESA with the Gram Panchayat Development Plan (GPDP) framework ensures that village-level planning is Gram Sabha-driven and rights-based.

- Academic Anchoring: The establishment of Centres of Excellence (CoE) in 16 universities, including Indira Gandhi National Tribal University (IGNTU), Amarkantak (supported by an ₹8.01 crore central grant), anchors specialised research and documentation of tribal customs.

- Normative Awareness: The annual observance of PESA Day on 24 December reinforces institutional commitment and public awareness regarding tribal autonomy.

- Digital Governance for Transparency and Monitoring: The launch of the PESA Portal and PESA Performance Indicators (launched 2024–25) enables the real-time tracking of funds, Gram Sabha decisions, and development outcomes.

- Accountability: Integration with digital planning tools improves the accountability of line departments and effectively reduces the administrative bypassing of Gram Sabhas.

- Inter-Ministerial Convergence for Tribal Empowerment: The Ministry of Panchayati Raj (MoPR) works in active coordination with the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) to align PESA with Forest Rights, livelihood missions, and cultural preservation.

- Linguistic Inclusion: Joint initiatives have led to the translation of PESA manuals into tribal languages such as Santhali, Gondi, Bhili, and Mundari, ensuring the law is accessible to the community.

- Constitutional Monitoring and Institutional Oversight: The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST) under Article 338A is mandated to monitor PESA implementation, examine violations of Gram Sabha consent, and advise governments on corrective measures.

- Checks and Balances: Periodic reports and field visits by the Commission provide a layer of constitutional oversight that goes beyond executive discretion.

- Governor’s Special Responsibility: Under Paragraph 5 of the Fifth Schedule, the Governor remains a constitutionally embedded protective mechanism, empowered to modify or suspend laws detrimental to tribal interests.

- Judicial Reinforcement of Tribal Rights: The Supreme Court of India, in the landmark Niyamgiri Judgment (2013), reaffirmed the primacy of Gram Sabha consent as a mandatory requirement in Scheduled Areas.

- Constitutional Morality: Judicial interpretation has consistently linked environmental protection and community consent with the broader framework of constitutional morality in tribal governance.

Protection of Tribals and Their Rights in India

- Constitutional Safeguards and Oversight:

- Administrative Framework: Article 244 and the Fifth Schedule provide a distinct administrative regime for Scheduled Areas, ensuring that general laws do not automatically override tribal customs.

- Constitutional Monitoring: The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST), established under Article 338A, provides specialized oversight, investigates violations of rights, and advises the government on tribal welfare.

- Socio-Economic Mandate: Under Article 46 of the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP), the State is constitutionally mandated to promote the educational and economic interests of Scheduled Tribes (STs) and protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.

- Legal and Regulatory Frameworks:

- Self-Governance: The Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA) secures the right to mandatory consultation and community-based decision-making through the Gram Sabha (Village Assembly).

- Resource Rights: The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (FRA) recognizes individual and Community Forest Rights (CFR), securing land tenure and access to Minor Forest Produce (MFP).

- Protection Against Land Alienation: The Fifth Schedule empowers State Governments and Governors to prohibit or restrict the transfer of tribal land to non-tribals, safeguarding customary ownership and preventing distress sales or arbitrary displacement.

- Institutional and Political Safeguards:

- Advisory Governance: Tribes Advisory Councils (TAC) are mandated to advise Governors on matters pertaining to the welfare and advancement of Scheduled Tribes within the State.

- Political Representation: The reservation of seats for Scheduled Tribes in the Lok Sabha (House of the People), State Legislative Assemblies, and Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) ensures their direct participation in the democratic law-making process.

- Cultural, Religious, and Judicial Protection:

- Identity Preservation: The Constitution protects tribal identity through Article 29 (Protection of interests of minorities) and Article 25 (Freedom of religion), safeguarding distinct languages, scripts, customary laws, and sacred landscapes.

- Judicial Sentinel: The Judiciary has repeatedly linked tribal rights with Article 21 (Right to Life with Dignity).

- In landmark rulings like the Niyamgiri Judgment (2013), the Supreme Court of India upheld the primacy of Gram Sabha consent and recognized cultural practices as integral to tribal survival.

- Environmental Justice: Courts have consistently intervened to protect against arbitrary displacement and have reinforced the link between environmental protection and community sovereignty.

- International Normative Support

- Global Alignment: India supports the principles of indigenous rights reflected in international instruments like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), 2007.

- Consent and Consultation: These global norms, focusing on Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), increasingly inform domestic judicial interpretations and policy discourse regarding large-scale development projects in tribal heartlands.

Way Forward

- Constitutional and Legal Reinforcement:

- Activising the Governor’s Special Responsibility: Governors must proactively exercise their discretionary powers under Paragraph 5 of the Fifth Schedule to modify or suspend State or Central laws that dilute PESA provisions.

- Regular reporting by Governors to the President of India and Parliament will ensure constitutional accountability.

- Legal Harmonisation: Existing statutes—including the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act (LARR), 2013 and the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act (MMDR)—must be explicitly aligned with the requirement for mandatory Gram Sabha consent.

- Clarifying Institutional Roles: Clear guidelines are required to harmonise the roles of Gram Sabhas under PESA and Community Forest Resource Management Committees (CFRMC) under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006. This will prevent jurisdictional ambiguity and administrative manipulation in forest governance.

- Fiscal Autonomy and Economic Federalism:

- Enabling Local Revenue Generation: Gram Sabhas should be empowered to levy, collect, and retain local taxes, fees, and resource royalties, particularly from Minor Minerals and Minor Forest Produce (MFP).

- Predictable Financial Devolution: Beyond local revenue, there must be a direct and predictable flow of funds from the Central Finance Commission (CFC) and State Finance Commission (SFC) to PESA Gram Panchayats to reduce dependency on State-level grants.

- Accountability and Democratic Oversight:

- Enhancing Political Accountability: State governments should be mandated to table Annual PESA Implementation Reports in State Legislatures.

- This introduces democratic oversight and subjects tribal governance to legislative scrutiny.

- Outcome-Based Monitoring: Institutionalise Social Audits and independent evaluations to assess the ground-level impact of Gram Sabha decisions.

- This ensures that the PESA–Gram Panchayat Development Plan (GPDP) Portal reflects actual empowerment rather than just digital data.

- Capacity Building and Rights Consciousness:

- Strengthening Legal Literacy: Continuous awareness campaigns in tribal languages (e.g., Santhali, Gondi, Bhili), utilizing community radio and Centres of Excellence (CoE), are needed to ensure communities understand and assert their statutory powers.

- Capacity Enhancement: Provide technical and legal training to tribal representatives to prevent “elite capture” and ensure that the most marginalized voices are heard within the Gram Sabha.

- Comparative Learning and Global Best Practices:

- Adapting Indigenous Models: India can draw insights from indigenous governance models in Latin America and Australia to balance modern development with the preservation of tribal identity and customary laws.

Conclusion

The PESA Mahotsav 2025 reaffirmed that tribal self-governance is a constitutional cornerstone of Indian democracy. By combining legal empowerment, institutional capacity, digital transparency, and cultural pride, PESA advances the vision of a Viksit Bharat where every Gram Sabha exercises a dignified, decisive, and constitutionally protected voice.

![]() 24 Dec 2025

24 Dec 2025

It integrates tribal governance into constitutional decentralisation, strengthening cooperative federalism and inclusive constitutionalism.

It integrates tribal governance into constitutional decentralisation, strengthening cooperative federalism and inclusive constitutionalism. Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra, recorded improved forest management through community-controlled Minor Forest Produce systems.

Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra, recorded improved forest management through community-controlled Minor Forest Produce systems.