Context:

Recently, the women’s reservation bill, also known as the Constitution (One Hundred and twenty- Eighth Amendment) Bill, 2023 was introduced in the Lok Sabha.

- The bill is named as ‘Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam’.

More on News:

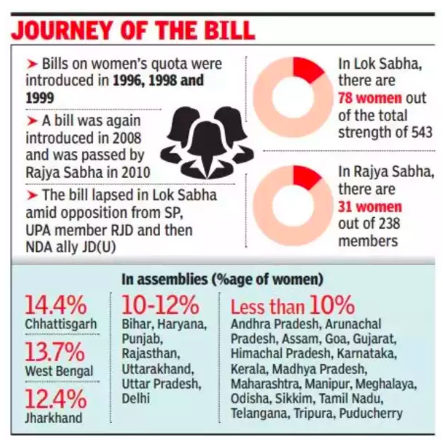

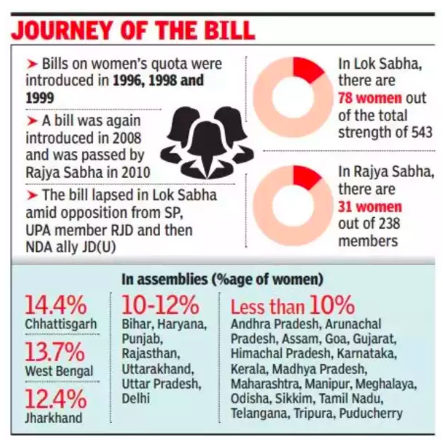

- The bill was first introduced in 1996, and passed in the Rajya Sabha in 2010, but hasn’t been tabled in the Lok Sabha.

Key Features of the Bill:

- Reservation in Lok Sabha: The bill mandates the reservation of one-third of the total seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament, for women.

- Introduction of News Article: The Bill, like the 108 Constitution Amendment Bill (passed by the Rajya Sabha in 2010), proposes to introduce new articles—Articles 330A and 332A—to the Constitution.

- These new provisions will introduce the changes for the Lok Sabha and Assemblies respectively.

- The crucial change, however, is a proviso added to Article 334 of the Constitution.

- Article 334 is the sunset clause for the reservation of seats for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Anglo-Indians.

- Extension to Delhi Assembly: The bill extends its provisions to the Legislative Assembly of the National Capital Territory of Delhi.

- One-third of the seats reserved for Scheduled Castes in the Delhi Assembly are also reserved for women.

- One-third of the total number of seats filled by direct election in the Delhi Assembly (including those reserved for women belonging to Scheduled Castes) are also reserved for women.

- Applicability to State Legislative Assemblies: The amendment applies to the legislative assemblies of all Indian states. It mandates the reservation of one-third of the total seats, including those for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, for women.

- Effective Post Delimitation: The provisions related to seat reservation for women in the Lok Sabha, State Assemblies, and Delhi Assembly will be implemented after a delimitation exercise is conducted. This process will be based on relevant census figures and will last for fifteen years from the commencement of the amendment.

- Rotation of Reserved Seats: The bill allows for the rotation of reserved seats for women in the Lok Sabha, State Assemblies, and Delhi Assembly after each subsequent delimitation exercise, as determined by Parliament.

| Arguments for the Bill |

Arguments against the Bill |

- Affirmative action needed to improve women’s condition in society

- Representation needed to address various societal issues like, low participation of women in the workforce, low nutrition levels, and a skewed sex ratio.

|

- Women are not a homogeneous community like a caste group, making reservations akin to caste-based reservations

- Reserving seats for women could be seen as a violation of the Constitution’s guarantee of equality, as it might not be based on merit

- Difficulty in implementing seat reservations for Rajya Sabha due to its election process using a single transferable vote system

|

Evolution of Women’s Political Representation in India:

- Pre-Independence:

- In 1931, Key women leaders Begum Shah Nawaz and Sarojini Naidu in their letter to the British PM emphasized equality in political status and rejected preferential treatment for women.

- Momentum in the 1970s: ‘Towards Equality’ Report

- In response to a UN request for a report on women’s status, the Committee on the Status of Women in India (CSWI) was appointed in 1971, revealing the Indian state’s failure in ensuring gender equality.

- 1987: National Perspective Plan and Constitutional Amendments:

- The union government formed a committee in 1987, presenting the National Perspective Plan for Women, leading to the Constitution 73rd and 74th Amendment Acts in the 1990s, mandating one-third reservation of seats for women in local and urban bodies.

- September 12, 1996: The First Women’s Reservation Bill

-

- The union government introduced The Constitution (81st Amendment) Bill, aiming to reserve one-third of seats for women in Parliament and state legislatures.

- Strong support for the Bill, but opposition from OBC MPs led to the Bill being sent to a Select Committee.

- 2008: The Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill

- The Bill sought to reserve one-third of all seats for women in Lok Sabha and the state legislative Assemblies, including one third of the seats reserved for SCs and STs.

- It was referred to the Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice.

- The Bill was passed by Rajya Sabha and it lapsed with the dissolution of the Lower House.

Gender Gap through Major Verticals:

Global Comparisons:

- Rwanda: 61% women in parliament.

- South Africa: 43% women in parliament.

- Bangladesh: 21% women in parliament.

- Norway: It implemented a quota system in 2003, requiring 40% of seats on corporate boards to be occupied by women.

|

- India’s Current Representation in Legislatures:

- Lok Sabha: 14% (78) women MPs.

- In the first Lok Sabha elections held in 1951, only 22 women MPs (4.41%) were elected out of 489 seats.

- Rajya Sabha: Approximately 11% women MPs.

- State legislature:

- The average number of women MLAs (Members of Legislative Assembly) across the nation is only 8%.

- Some states like Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Jharkhand, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Delhi have slightly higher representation above 10%.

- India ranks 144 out of 193 countries for women’s representation in Parliament, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s latest report.

Women as voters in parliament:

Women as voters in parliament:-

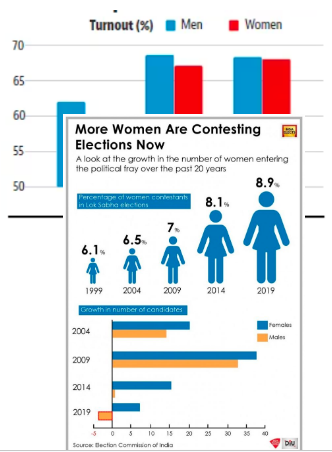

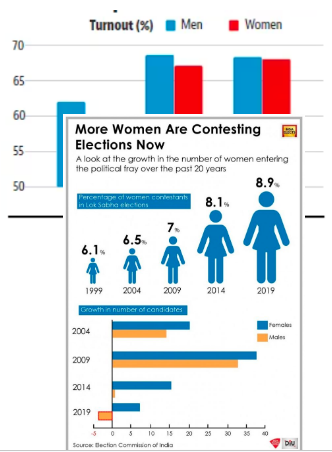

- In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections: According to reports, Gender gap in voter turnout reversed by 0.17 percentage points compared to a -16.71 gap in 1962.

- Registered voters increased to 438,491,517 from 397,049,094 in 2014.

- Gender ratio improved to 930 in 2018 from 908 in 2014, signifying increasing gender parity in voter turnout.

- Women as Electoral Candidates:

- The percentage of women contesting as candidates has marginally increased from 6.11 percent from the 1999 Lok Sabha elections to only around 9 percent.

Need for the Bill:

- Impact of Women’s Representation:

- Studies suggest that a higher proportion of women in national parliament correlates with passing and implementing gender-sensitive laws.

- Female representation in local councils (e.g., village councils) has shown to increase participation and responsiveness to various community concerns, including infrastructure, sanitation, and water.

- Addressing Patriarchy in Political Parties: Affirmative action is crucial to counter the inherent patriarchal nature of political parties, ensuring fair representation for women.

- Importance of Women’s Representation: Higher representation of women in Parliament is essential to drive effective discussions and policy-making on women-specific concerns.

- India ranks 127 out of 146 countries on the Global Gender Gap 2023, highlighting the existing gender disparities.

- Slow Progress in Political Empowerment: Despite slight gains, political empowerment for women remains slow, with women constituting only about 15% of parliamentarians.

- Addressing Societal Challenges: More women in decision-making roles are essential to tackle pressing issues such as crimes against women, skewed sex ratios, and low nutrition levels.

Benefits of Women’s Participation in Local Self-Governance:

- Increased Representation and Empowerment: Their is a substantial increase in women’s representation due to the 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act, which mandated 33.3% reservation for women in PRIs.

- Out of the total 1.3 lakh Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) representatives in Bihar, over 71,000 are women. Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh, out of the 9.1 lakh representatives, 3,04,638 are women.

- This increase in representation has empowered women to take an active part in local governance, allowing them to contribute meaningfully to their communities.

- Focus on Development Priorities: Women leaders often prioritize essential public services such as healthcare, education, and sanitation.

- Research shows that constituencies reserved for women leaders have a higher delivery of civic facilities (drinking water, schools, health centres, fair price shops).

- Role Models and Inspiration: The women in leadership positions become role models for other women and girls, inspiring them to participate in public life.

Challenges in women’s participation in India’s electoral landscape:

- Structural Norms and Gender Discrimination: Women’s limited political voice and representation stem from long-standing structural norms and deep-rooted gender discrimination present in Indian society.

- These norms create barriers for women to fully participate in the political arena.

- Societal Prejudices and Political Party Practices: Societal prejudices against women are perpetuated within political parties. These prejudices influence the allocation of seats and the hierarchy within political parties, limiting women’s access to key positions and opportunities to contest elections.

- Lack of Authority and Influence: Women often lack positions of authority and influence within political networks. This lack of influence diminishes their ability to shape policy decisions and have a meaningful impact within the political sphere.

- Dynastic and Celebrity Backgrounds: Women from dynastic and celebrity backgrounds might have more visibility and recognition, giving them an advantage over others.

- Sarpanch-patism: Recently, the Supreme Court raised the concern that the Men often wielding the actual power behind elected women who remain “faceless wives and daughters-in-law” in grassroots politics.

Way forward for women’s political empowerment in India:

- Implement the Women’s Reservation Bill: Actively revive and pass the bill to reserve 33% of seats for women in the Lok Sabha and state legislative assemblies. This will provide a solid legal framework for promoting gender parity.

- Ensure Inclusive Allocation of Party Tickets: Encourage political parties to allocate a significant number of party tickets to women, focusing on merit and potential rather than tokenism or dynastic considerations.

- Promote Gender Mainstreaming: Advocate for gender mainstreaming within legislatures, drawing lessons from successful practices in countries like Cuba, Mexico, Rwanda, and New Zealand. This involves integrating a gender perspective into all policies and programs.

Conclusion:

India must carefully plan seat reservations for women to boost their representation in legislatures. Reservation is vital but needs to be coupled with broader investment in empowering women’s leadership, both politically and socially.

News Source: The Indian Express

![]() 19 Sep 2023

19 Sep 2023

Women as voters in parliament:

Women as voters in parliament: