Recently, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) released the second edition of its landmark publication on State Finances.

- The first edition of the report, ‘State Finances 2022-23’ was released in September 2025.

About CAG

- Established under Article 148 of the Indian Constitution, the CAG plays a critical role in ensuring transparency, accountability, and financial discipline in governance.

|

About the Second Edition of the Publication on State Finances (2023-24)

- Pan-India Audit of State Finances and Federal Fiscal Health: This report serves as a comprehensive audit of the fiscal trajectories of all 28 Indian States.

- It is moving beyond individual state reports to provide a unified, comparative analysis of India’s federal financial health.

- Constitutional Basis and Authoritative Nature of State Accounts: Under the mandate of Article 150 of the Constitution, the CAG prepares annual Finance Accounts and Appropriation Accounts.

- These documents function as the authoritative record of a State’s financial standing, capturing every flow of revenue receipts, capital expenditure, and public debt to ensure transparency and accountability to the State Legislature.

Crucial Insights on the Second Edition of the Publication on State Finances (2023-24)

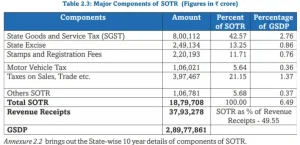

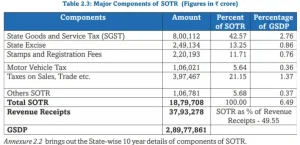

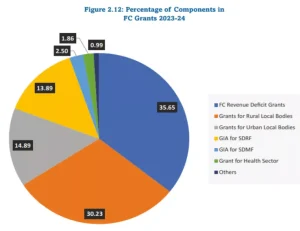

- Revenue Composition: Total revenue receipts reached ₹37.93 lakh crore.

- States’ Own Tax Revenue (SOTR) emerged as the primary pillar of self-reliance, accounting for 50% of total income, followed by Central Tax Devolution at 30%.

- Skewed Expenditure Profile: Out of the total spending of ₹46.81 lakh crore, a massive 83.25% was diverted toward Revenue Expenditure (consumption).

- This indicates that a large portion of funds is used for operational costs rather than creating productive assets.

Key Terms:

- States’ Own Tax Revenue (SOTR): It refers to the tax income that State governments raise on their own, using the taxation powers granted to them under the Constitution of India.

- It is a key indicator of a state’s fiscal autonomy and revenue capacity.

- Ways and Means Advances (WMA): A short-term credit facility provided by the RBI to the Centre and States to meet temporary cash-flow mismatches.

- It is interest-bearing, time-bound, and meant for liquidity management, not for financing fiscal deficits.

- Overdrafts (OD): Overdrafts arise when governments exceed the WMA limit with the RBI.

- Outstanding Public Debt of States: It refers to the total borrowings by state governments, including loans and bonds, that remain unpaid.

- It reflects the financial health of states, impacting fiscal sustainability and the ability to finance development without excessive borrowing.

|

-

-

- Operational costs are recurring expenditures incurred to run day-to-day activities (like salaries and maintenance), while productive assets are long-term investments (like infrastructure or machinery) that generate sustained economic returns and enhance future productive capacity.

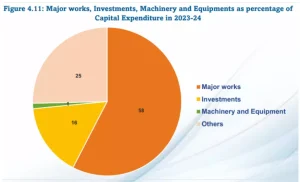

- Sectoral Priorities: The report classifies spending into three functional heads:

- Social Sector (Human Capital)

- Economic Sector (Infrastructure)

- General Sector (Administration)

- While the Economic sector sees the highest Capital Outlay, the General sector remains largely revenue-intensive.

- Liquidity Management: To bridge temporary gaps between cash inflows and outflows, 16 states resorted to Ways and Means Advances (WMA) and Overdrafts from the RBI.

- Alarmingly, states like Telangana and Andhra Pradesh remained dependent on these advances for nearly the entire year.

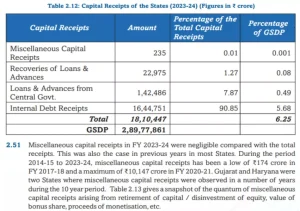

- Outstanding Public Debt of States: It reached ₹67.87 lakh crore as of March 2024, equivalent to 23.42% of combined Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP).

| Key Comparison: First Edition vs. Second Edition |

| Feature |

First Edition (Initial Publication) |

Second Edition (2023–24) |

| Temporal Scope |

- Focused primarily on immediate fiscal years with limited historical context.

|

- Provides a robust 10-year Trend Analysis (2014–15 to 2023–24), capturing the long-term impact of GST and the Pandemic.

|

| Data Granularity |

- Focused on macro-level fiscal aggregates (Total Revenue, Total Expenditure).

|

- Offers Object-Head Level Analysis, breaking down spending into specific units like Salaries, Pensions, and Subsidies.

|

| Standardization |

- Based on diverse state-specific accounting classifications.

|

- Aligns state expenditure with the Revised List of Common Object Heads notified by the Union Government for better comparability.

|

| Analytical Depth |

- Primarily a summary of audited figures for the preceding financial year.

|

- Introduces a Fiscal Capacity Assessment, comparing the ability of different states to raise Own Tax Revenue (SOTR).

|

| Liquidity Monitoring |

- General mention of cash balances and treasury positions.

|

- Detailed scrutiny of Ways and Means Advances (WMA) and Overdraft usage, highlighting chronic dependency in specific states.

|

| Sectoral Insights |

- Basic classification into General, Social, and Economic sectors.

|

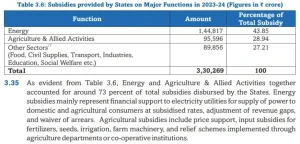

- Deep dive into Subsidies, specifically identifying the Power and Agriculture sectors as the primary drivers of revenue outgo.

|

Significance of the Report

- For Fiscal Federalism:

- Addressing Vertical & Horizontal Imbalance: The report provides the Finance Commission with audited, comparable data to bridge the “Vertical Imbalance” (centralized revenue vs. decentralized expenditure) and determine the “Horizontal Devolution” (sharing among states) based on their actual fiscal performance.

- Evidence-based Policymaking: By identifying states with high SOTR buoyancy versus those dependent on central grants, the report helps the Union Government to frame “Special Category” status or specific central assistance programs.

- Inter-state Peer Pressure (Benchmarking): The consolidated nature of the report creates a “naming and shaming” or “competitive” effect, encouraging low-performing states to adopt the fiscal best practices of high-performing states like Odisha or Maharashtra.

- For Legislative Oversight:

- Empowering the Public Accounts Committee (PAC): The report acts as the primary “working paper” for the PAC of state legislatures.

- It translates complex accounts into actionable “Audit Paras,” allowing legislators to hold the Executive accountable for financial lapses.

- About Public Accounts Committee (PAC): A Parliamentary financial committee that examines CAG reports on government accounts to ensure legality, economy, and efficiency of expenditure.

- Checking Executive Overreach: Detailed analysis of Personal Deposit (PD) Accounts and Abstract Contingent (AC) Bills prevents the Executive from “parking” funds outside the Consolidated Fund to avoid legislative scrutiny at the end of the financial year.

- About Personal Deposit (PD) Accounts: PD Accounts are government accounts operated by designated officers to manage departmental funds.

- They provide flexibility in spending but may lead to fund parking and reduced legislative control.

- Abstract Contingent (AC) Bills: AC Bills are temporary withdrawal bills used for urgent expenditure without full details.

- They must be adjusted through DC Bills, otherwise they reflect poor financial discipline.

- Upholding the “Power of the Purse”: It ensures that the government spends money only in the manner and amount authorized by the Appropriation Act, reinforcing the constitutional principle of legislative control over public money.

- For Macro-Economic Stability:

- RBI’s Monetary Policy Inputs: The Reserve Bank of India uses these audited figures to manage the State Development Loans (SDLs) market and monitor the overall General Government Debt (Centre & States), which is crucial for controlling inflation and interest rates.

- Debt Sustainability Analysis: The report applies the “Golden Rule of Hoarding”—checking if borrowings are used for Capital Expenditure (asset creation) or merely to fund Revenue Deficits (consumption).

- This is critical to prevent states from falling into a “Debt Trap.”

- National Income Estimation: The National Statistical Office (NSO) relies on this audited data for accurate Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) calculations, ensuring that national economic growth figures are grounded in verified financial reality.

- About National Statistical Office (NSO): It is India’s nodal statistical body under the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI).

- It is responsible for collecting, compiling, and disseminating official statistics to support data-driven policymaking and national planning.

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures the total value of final goods and services produced within a country, while Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) captures the same measure at the state level, together indicating national and sub-national economic performance.

- For Governance & Transparency:

- Democratizing Public Finance: By making the second edition available in a consolidated format, the CAG “democratizes” data for civil society, media, and think tanks, allowing for informed public debate on “Populism vs. Development” (Freebies/Subsidies vs. Infrastructure).

- Catalyst for Accounting Reforms: The report’s push for a Uniform List of Object Heads by 2027 is a significant reform in the “Public Financial Management System” (PFMS), moving India toward international standards of government accounting.

- About Public Financial Management System (PFMS): It is a Central Government digital platform under the Ministry of Finance.

- It tracks fund flow, expenditure, and payments in real time, ensuring transparency, efficiency, and accountability in public finance management.

- Certification for Global Funding: Audited accounts are a prerequisite for states to access loans from international bodies like the World Bank or Asian Development Bank (ADB) for “Externally Aided Projects.”

| PWOnlyIAS Extra Edge:

CAG Report as the “Empirical Bedrock” for the 16th Finance Commission:

- The CAG’s Second Edition (2023-24) serves as more than just an audit; it is the primary evidentiary tool for the 16th Finance Commission (FC) as it finalizes the award for FY 2026-31.

- Evidence-Based Horizontal Devolution: The report provides the Commission with audited, comparable data to refine the devolution formula.

- By highlighting uneven fiscal capacity—where industrialized states (Maharashtra, Gujarat) boast high SOTR Buoyancy compared to the structural dependence of North-Eastern/Hill states, the CAG data enables the Commission to balance equity with efficiency.

- Addressing the “Debt-Sustainability” Gap: With the CAG flagging that 13 states have breached the 33.1% Debt-to-GSDP ceiling, the 16th FC can use this data to design fiscal consolidation glide paths.

- This is crucial for evaluating state demands for higher devolution (up to 50%) against their actual fiscal discipline.

- Validating Special Assistance Claims: States like Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh often seek “Green Bonuses” or disaster relief flexibility.

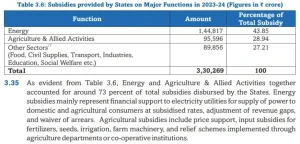

- The CAG’s granular data on Committed Expenditure rigidity and Subsidy burdens (73% concentrated in Power/Agri) allows the Commission to distinguish between structural fragility and fiscal mismanagement.

- Shadow Debt & Transparency: The report’s focus on Off-budget Liabilities and Personal Deposit (PD) Accounts supports the Commission’s mandate to review disaster management financing and ensure that central transfers are not simply “parked” to avoid budgetary lapse.

Quantitative Trends (2014-15 to 2023-24)- A Decadal Shift in Fiscal Autonomy:

- The 10-year Trend Analysis in the Second Edition provides a unique “macro-view” of the post-GST and post-Pandemic fiscal landscape.

- The Rise of SOTR & Devolution: Over the last decade, the combined share of States’ Own Tax Revenue (SOTR) and Central Tax Devolution has stabilized at approximately 50% and 30% respectively.

- This indicates a maturing of the GST regime and a steadying of the Divisible Pool.

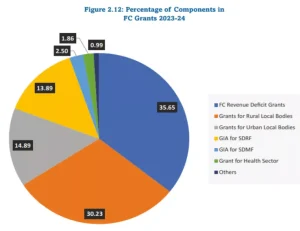

- Declining Dependency on Grants: A significant trend is the gradual decline of Grants-in-Aid to ~12% in FY24.

- This suggests that states are moving toward revenue self-reliance, although the CAG warns that this “average” masks a widening inter-state disparity.

- The Persistence of Vertical Imbalance: Despite rising revenues, states still handle nearly two-thirds of public expenditure while collecting less than one-third of direct revenues.

- This mismatch, documented by the CAG, reinforces the argument for the 16th FC to protect the states’ share from being eroded by increasing Central Cesses and Surcharges.

- The “Rigidity” Constraint: The decade-long data confirms a hardening of Committed Expenditure.

- The fact that nearly 60% of revenue (including subsidies) is now pre-committed poses a long-term risk to Capital Outlay, which the 16th FC must address through incentive-based grants.

|

| Comparison of Fiscal Capacity: High-Performing vs. Low-Performing States (FY 2023-24) |

| Category |

States Involved |

SOTR as % of Total Revenue Receipts |

Key Characteristics |

| Top 6 States (High Fiscal Capacity) |

- Haryana, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat

|

|

- High industrialization, robust services sector, and higher tax buoyancy.

|

| Bottom 6 States (Low Fiscal Capacity) |

- Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura

|

|

- Heavy reliance on Central Transfers and Grants-in-Aid due to geographical and structural constraints.

|

Emerging Fiscal Risks at the State Level

- Deepening Fiscal Rigidity: The most significant concern is the shrinking fiscal space available for discretionary spending.

- Dominance of Committed Expenditure: Nearly 43.3% of revenue expenditure is consumed by Salaries, Pensions, and Interest Payments.

- When Subsidies are included, this figure climbs to approximately 60%.

- The Salary “Shadow”: The report highlights Grants-in-Aid (Salary), where states provide funds to autonomous bodies to pay their staff.

This often masks the true scale of the state’s wage bill, making the actual committed burden even higher than official salary heads suggest.

This often masks the true scale of the state’s wage bill, making the actual committed burden even higher than official salary heads suggest.

- The Pension Burden: Seven states are already spending over 15% of their total budget on pensions alone, a figure expected to rise with increasing life expectancy and the debate around pension reforms.

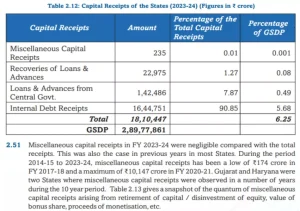

- Debt Sustainability and Breaching Thresholds: While the Union Government sets targets for fiscal discipline, many states are struggling to adhere to them.

- Breaching GSDP Limits: The 15th Finance Commission set a debt ceiling of 33.1% of GSDP.

- However, 13 states have already crossed this limit, with Arunachal Pradesh reaching as high as 50.85%.

Fiscal Deficit Overruns: Despite an indicative benchmark of 3% of GSDP, 18 states recorded fiscal deficits above this threshold in FY 2023-24.

Fiscal Deficit Overruns: Despite an indicative benchmark of 3% of GSDP, 18 states recorded fiscal deficits above this threshold in FY 2023-24.- Off-Budget Guarantees: Outstanding state guarantees—where the government promises to repay loans if a state entity defaults—have nearly tripled over the last decade, reaching ₹11.5 lakh crore.

- This poses a significant contingent liability risk to state exchequers.

- Poor Quality of Expenditure: The “health” of public spending is determined by the ratio between consumption and investment.

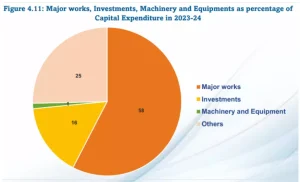

Revenue vs. Capital Mismatch: Revenue expenditure (running costs) continues to dominate at 83.25%, leaving only 16.75% for Capital Expenditure (asset creation).

Revenue vs. Capital Mismatch: Revenue expenditure (running costs) continues to dominate at 83.25%, leaving only 16.75% for Capital Expenditure (asset creation).- Multiplier Effect Lost: Since capital spending creates infrastructure that generates future revenue, its relatively small share limits the future growth potential of the GSDP.

- Subsidy Concentration: Subsidies are heavily concentrated in Energy (Power) and Agriculture, accounting for 73% of total subsidies.

- This “leakage” often prevents funds from being diverted to more productive areas like vocational training or industrial incentives.

Chronic Liquidity Stress: The reliance on the RBI for temporary cash flow management has moved from an emergency measure to a routine necessity for some states.

Chronic Liquidity Stress: The reliance on the RBI for temporary cash flow management has moved from an emergency measure to a routine necessity for some states.

- Continuous WMA Usage: States like Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Rajasthan utilized Ways and Means Advances (WMA) and Overdrafts for over 320 days in a single year.

- Lack of Standardized Accounting (Transparency Gap):

- Varying Object Heads: The report notes that states use different classification codes (Object Heads) for spending, making it difficult to compare performance accurately across the country.

- Implementation Delays: Although the CAG has mandated a transition to a uniform system by FY 2027-28, the interim period remains characterized by data silos and accounting inconsistencies that hinder a “pan-India” fiscal analysis.

Way Forward

- Enhancing Expenditure Quality (Capital vs. Revenue): The primary objective for states should be to shift the focus from Revenue Expenditure (consumption) to Capital Outlay (investment).

-

- Targeting the Multiplier Effect: States must prioritize spending on the Economic Sector (infrastructure, power, and transport), as every rupee spent here has a higher multiplier effect on the GSDP compared to revenue spending.

- Rationalizing Subsidies: There is an urgent need to move from broad-based subsidies to Targeted Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT). Specifically, leakages in the Power and Agriculture sectors (which consume 73% of subsidies) must be plugged to free up funds for social infrastructure like schools and hospitals.

- Ensuring Debt Sustainability: With 13 states breaching the 33.1% debt-to-GSDP ceiling, fiscal consolidation is no longer optional.

- Adherence to Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Targets: States must align their Fiscal Deficit with the 3% benchmark set by the 15th Finance Commission. Borrowing should be strictly monitored to ensure it is used for asset creation rather than funding committed liabilities.

- Managing Contingent Liabilities: States must strengthen their Guarantee Redemption Funds (GRF). The fact that five states (Bihar, HP, Jharkhand, Kerala, Punjab) have not yet established this fund is a concern that must be addressed to safeguard against defaults by state PSUs.

- About Guarantee Redemption Funds (GRF): These are reserve funds set up by state governments to ensure repayment of loans or guarantees provided to public sector undertakings (PSUs).

- They act as a safeguard to cover default risks, maintaining fiscal discipline and creditworthiness.

- Revenue Augmentation (Boosting SOTR): To reduce dependency on Central Devolution and Grants-in-Aid, states must broaden their own tax bases.

- Improving Tax Buoyancy: States need to leverage technology for better GST compliance and audit. Since the buoyancy ratio is currently 0.92, there is significant room to ensure tax growth outpaces economic growth through better administration.

- Tapping Non-Tax Revenue (SNTR): States should modernize the management of State Public Sector Undertakings (SPSUs) to ensure they provide regular dividends and interest, rather than becoming a drain on the exchequer.

- Structural Reform in Accounting (The 2027 Mandate): Transparency is the bedrock of fiscal discipline. The CAG’s directive to standardize Object Heads is a critical reform.

- Unified Accounting Architecture: By adopting the revised list of Common Object Heads by FY 2027–28, India will achieve a “one-nation-one-accounting” standard. This will allow for real-time comparison of how public money is spent at the most granular level.

- Monitoring Off-Budget Borrowings: Enhanced disclosure norms are required to bring “hidden” debts—often taken by state entities but backed by government guarantees—onto the main budget balance sheet.

- Prudent Cash Management: The chronic dependence on Ways and Means Advances (WMA) indicates poor financial planning.

- Treasury Single Account (TSA): Implementing a robust TSA system can help states monitor their cash balances in real-time, reducing the need for expensive short-term borrowing from the RBI.

- Smoothing Expenditure Flows: States should avoid “March Rush” (heavy spending at the end of the fiscal year) and instead ensure a steady flow of expenditure throughout the year to match revenue patterns.

Conclusion

The CAG’s Second Edition underscores the urgent need for States to enhance fiscal autonomy, prioritise capital expenditure, rationalise subsidies, and adhere to debt sustainability norms. These reforms will strengthen fiscal federalism, ensure macroeconomic stability, and foster equitable and sustainable development across India.

![]() 7 Jan 2026

7 Jan 2026

This often masks the true scale of the state’s wage bill, making the actual committed burden even higher than official salary heads suggest.

This often masks the true scale of the state’s wage bill, making the actual committed burden even higher than official salary heads suggest. Fiscal Deficit Overruns: Despite an indicative benchmark of 3% of GSDP, 18 states recorded fiscal deficits above this threshold in FY 2023-24.

Fiscal Deficit Overruns: Despite an indicative benchmark of 3% of GSDP, 18 states recorded fiscal deficits above this threshold in FY 2023-24. Revenue vs. Capital Mismatch: Revenue expenditure (running costs) continues to dominate at 83.25%, leaving only 16.75% for Capital Expenditure (asset creation).

Revenue vs. Capital Mismatch: Revenue expenditure (running costs) continues to dominate at 83.25%, leaving only 16.75% for Capital Expenditure (asset creation). Chronic Liquidity Stress: The reliance on the RBI for temporary cash flow management has moved from an emergency measure to a routine necessity for some states.

Chronic Liquidity Stress: The reliance on the RBI for temporary cash flow management has moved from an emergency measure to a routine necessity for some states.