Recently, the Supreme Court upheld that states have the authority to subdivide reserved category groups based on their varying levels of backwardness to extend reservation benefits.

- In doing so, the apex court overturned a 2004 ruling in the EV Chinnaiah vs State of Andhra Pradesh case, which had held that such sub-classification was not permissible since the Scheduled Castes (SC)/Scheduled Tribes (ST) constituted “homogenous” classes.

Background for Sub-Categorisation of Scheduled Caste

Article 341 of the Constitution allows the President, through a public notification, to list as SC “castes, races or tribes” that suffered from the historical injustice of untouchability. SC groups are jointly accorded 15% reservation in education and public employment.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

- Sub-Categorisation by Punjab Government, 1975: Punjab government divides its 25% SCs reservation into two categories:

- Reserved for the Balmiki and Mazhbi Sikh communities (most economically and educationally backward communities).

- Thus, they were to be given first preference for any reservations in education and public employment.

- Rest of the SCs communities, which didn’t get this preferential treatment.

- Formation of Justice Ramachandran Commission, 1996: The Andhra Pradesh government formed the Commission.

- The commission proposed sub-categorisation of SCs in the State based on evidence that some communities were more backward and had less representation than others.

- Andhra Pradesh Scheduled Castes (Rationalisation of Reservations) Act, 2000: The Andhra Pradesh government introduced this act for an expansive list of SC communities identified in the state and the quota of reservation benefits provided to each of them.

- E.V. Chinnaiah v State of Andhra Pradesh, 2004: A five-judge constitution bench struck down the Andhra Pradesh Scheduled Castes (Rationalisation of Reservations) Act, 2000 for being violative of the right to equality.

- The Court held that the sub-classification would violate the right to equality by treating communities within this category differently and the SC list must be treated as a single, homogenous group.

- Decision by Punjab & Haryana High Court: In 2004, the Court, in Dr. Kishan Pal vs State of Punjab, struck down the 1975 notification, supporting the E.V. Chinnaiah decision.

- Punjab Scheduled Caste and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act, 2006: The Punjab government attempted to bring back the law by passing this act.

- Appeal to Supreme Court: In 2010, the Punjab government subsequently appealed against the High Court’s decision, contending that the SC’s 2004 judgement had incorrectly concluded that sub-classification within the Scheduled Caste quota is not permissible.

- Davinder Singh v State of Punjab, 2014: The SC referred the appeal to a five-judge constitution bench to determine if the E V Chinnaiah of 2004 required reconsideration since it needed an inquiry into the interplay of several constitutional provisions.

-

- Interpretation of the Constitution requires a bench of at least five-judges of the Supreme Court.

- Jarnail Singh v Lachhmi Narain Gupta, 2018: In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the concept of “creamy layer” within SCs too.

- The ‘Creamy layer’ concept puts an income ceiling on those eligible for reservations.

- While this concept applies to Other Backward Castes (OBC), it was applied to promotions of SCs for the first time in 2018.

Crucial Insights on the Supreme Court Judgement

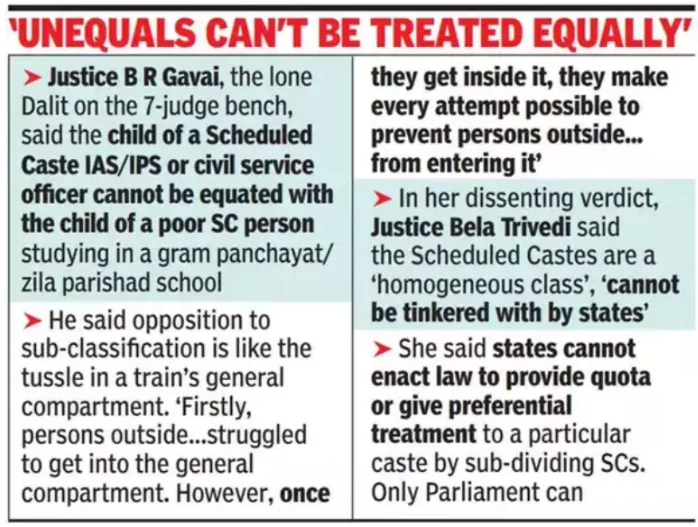

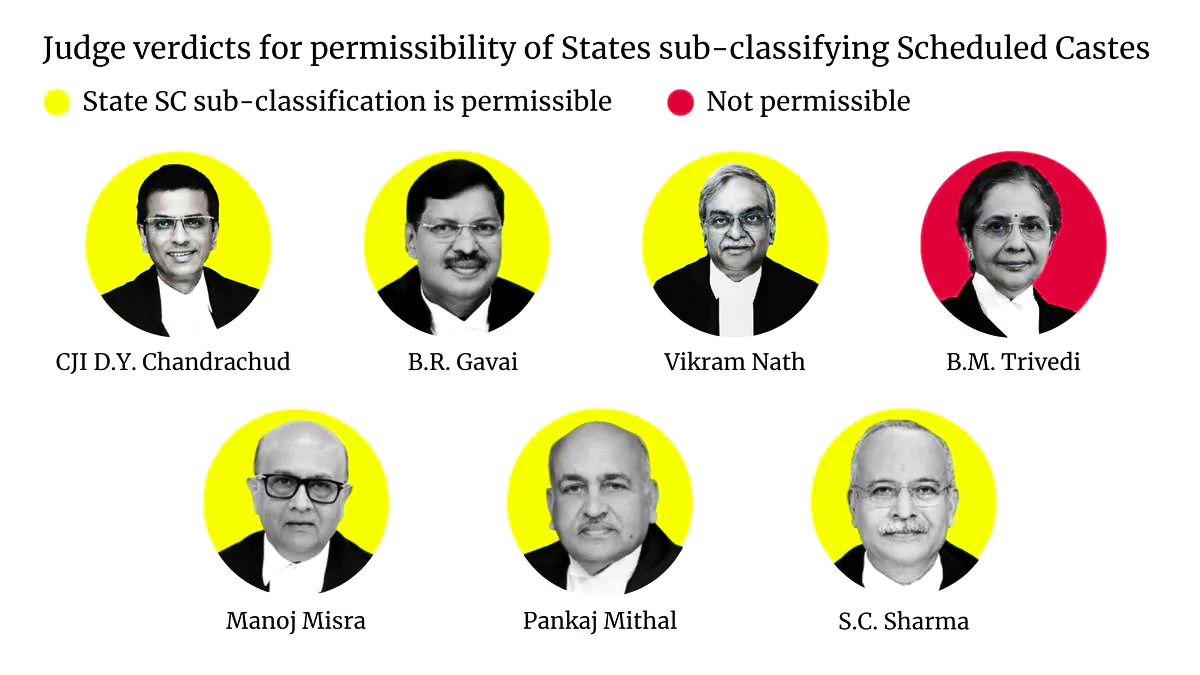

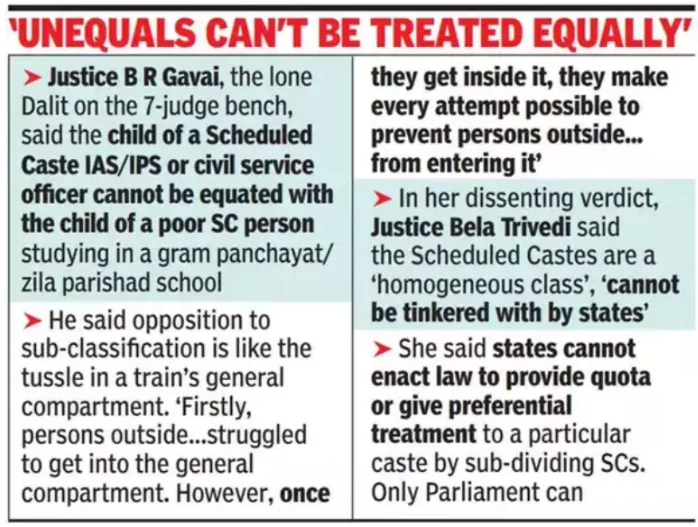

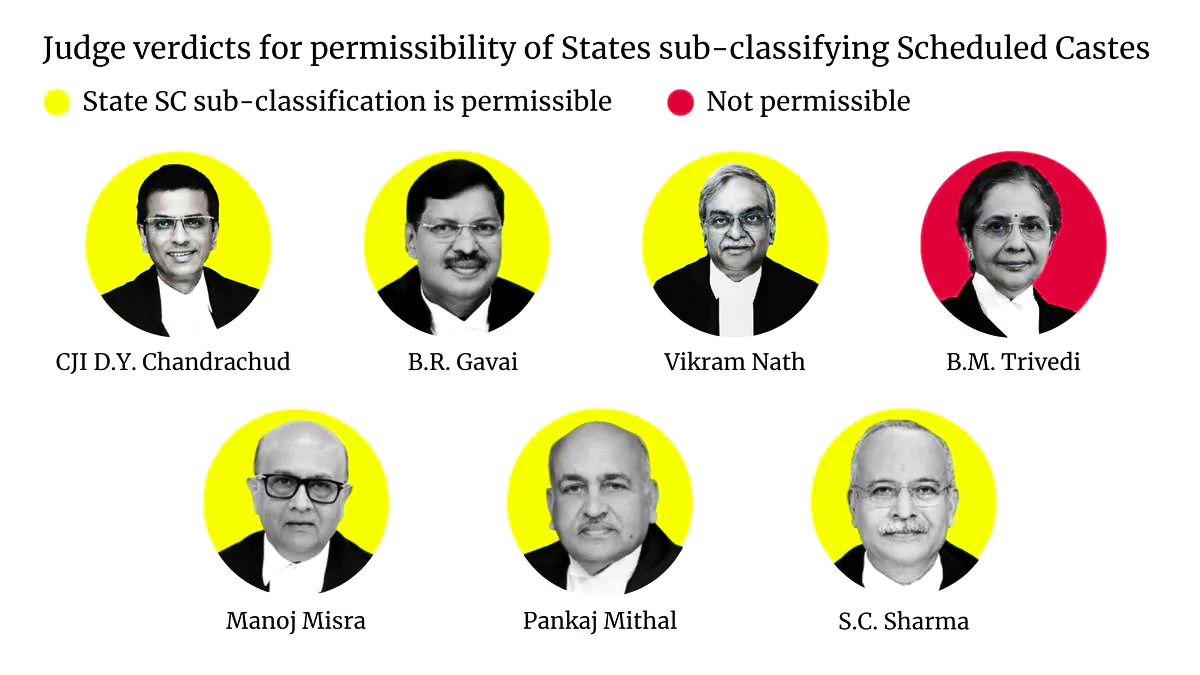

In a In a 6:1 ruling, the Supreme Court Bench holds that sub-categorisation within a class is a constitutional requirement to secure substantive equality.

- On Legal Fiction: As per the Supreme Court, the Presidential list of SCs is a “legal fiction” — something that does not exist in actuality but is “treated as real and existing for the purpose of law”.

- A Scheduled Caste is not something that existed before the Constitution came into force, and is recognised so that benefits can be provided to communities in the list.

- This legal fiction cannot be “stretched” to claim that there are no “internal differences” among SCs.

- On Sub-Classification of the Presidential List: The majority opinion held that “the State in exercise of its power under Articles 15 and 16 is free to identify the different degrees of social backwardness and provide special provisions (such as reservation) to achieve the specific degree of harm identified”.

- Articles 15(4) of the Constitution gives states the power to make “any special provision” for the advancement of SCs.

- Article 16(4) gives states the specific power to provide reservations of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which is not adequately represented in the services of the State.

- The equality of opportunity (Article 16) must account for the varying social positions of different communities. When the same opportunities are provided to SC communities that are on different footings it “can only mean aggravation of inequality”.

- On the Yardstick for Sub-Classification: The majority opinion drew stringent redlines for states on how to work out the sub-quotas. States will have to demonstrate a need for wider protections, bring empirical evidence, and have a “reasonable” rationale for classifying sub-groups. This reasoning can be further tested in court.

- The Chief Justice of India underlined that any form of representation in public services must be in the form of “effective representation”, not merely “numerical representation”.

On Applicability of ‘Creamy Layer’ Principle: Only the opinion of Justice Gavai bats for introducing the ‘creamy layer’ exception for SCs (and STs) that is already followed for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) as highlighted in Indra Sawhney Case.

On Applicability of ‘Creamy Layer’ Principle: Only the opinion of Justice Gavai bats for introducing the ‘creamy layer’ exception for SCs (and STs) that is already followed for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) as highlighted in Indra Sawhney Case. -

- This concept places an income ceiling on reservation eligibility, ensuring that the beneficiaries are those in a community that need quotas the most.

- Concerns Raised: Experts have however questioned why the judges ventured into the applicability of the creamy layer principle for SCs and STs, given that the petitions before them were concerned solely with the issue of sub-categorisation.

- However, such observations are within the realm of obiter dicta – those sections of a judicial opinion that are not relevant to the court’s decision and would therefore lack the force of law and any binding precedent.

- Obiter dictum is a Latin phrase meaning “other things said”, that is, a remark in a legal opinion that is “said in passing” by any judge or arbitrator. It is a concept derived from English common law.

Check Out UPSC CSE Books From PW Store

| Issues to be Decided |

Decisions Held |

- Whether sub-classification is Permissible?

|

- Yes, Scheduled Castes can be further classified if:

- There is a rational principle for differentiation

- If the rational principle has a nexus with the purpose of sub-classification

- “Sub-classification is one of the means to achieve substantive equality”.

|

- Is Scheduled Caste Homogenous?

|

- No, Scheduled Castes are not a homogenous integrated class because empirical evidence indicates that there is inequality even within the Scheduled Castes.

|

- Whether Article 341 creates a homogenous class by deeming Fiction?

|

- No, because the inclusion in the Presidential list does not automatically lead to the formation of a uniform and internally homogenous class which cannot be further classified.

- Article 341 creates a legal fiction for the limited purpose of identification of Scheduled Castes by distinguishing them from other groups.

|

- Are States competent to create sub-classifications within Reserved Categories?

|

- While the State may embark on an exercise of sub-classification, it must do so on the basis of quantifiable and demonstrable data bearing on levels of backwardness and representation in the services of the State.

- The model of sub-classification will be unconstitutional if it excludes some Scheduled Castes from the benefit.

|

About Caste and Sub-Caste

The Caste System in India is a social hierarchy that has existed for centuries, traditionally dividing people into different groups based on their occupations and social roles.

- Categories: It is associated with main categories- Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), and Shudras (labourers and service providers) and the outcastes.

- Sub-Castes: There are numerous sub-castes and sub-groups within each of these main categories. These sub-castes often originated from regional, occupational, or social distinctions.

About Sub-Classification of SC and ST

It is the process of creating sub-groups within the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes to ensure a more equitable distribution of reservation benefits, targeting the most backward or marginalised within these communities.

- Need: Over the years, states have argued that some groups within the SC list have been underrepresented compared to others.

- They believe that a separate quota for some castes within the SC quota of 15% should be created to ensure that the benefits are equitably distributed among all castes.

- Demand: Over time, some communities have sought recognition and specific privileges based on their unique characteristics, historical backgrounds or socio-economic status.

- Sub-categorization attempts to address the diversity within larger caste groups and provide targeted benefits to specific sub-groups that may be perceived as socially and economically disadvantaged.

- Power Lies in: Article 341(1) of the Constitution gives the President the power to “specify the castes, races or tribes” in a state, which shall “for the purposes of this Constitution be deemed to be Scheduled Castes in relation to that State or Union territory, as the case may be”.

- Following such a notification, Article 341(2) states that only Parliament can include or exclude “any caste, race or tribe” from the list of SCs.

- The Sub-Categorisation Policy Being Practised:

- Tamil Nadu: In 2009, it made a special reservation provision for employment and education for Arunthathiyars within the 18 per cent reservation for SCs in the state.

- Bihar: In 2007, it created a group called ‘Mahadalits’ (most backward Dalits) which excluded the Chamar, Dhobi, Paswan and Dushad castes among 22 Scheduled Castes.

- Later in 2015, all castes were declared Mahadalit except Paswans.

- Bihar gave welfare scheme priority to Mahadalits and did not tamper with Constitutional reservations.

- Haryana: In 2020, it split reservations in admissions through legislation by creating a new group of SCs called “Deprived Scheduled Castes”.

- This group included 36 Scheduled Castes, leaving out the Chamar and Ravidasia communities.

Check Out UPSC NCERT Textbooks From PW Store

Need for Sub-Categorisation of Castes

To gain true equality, the State must evolve a policy to identify creamy layers among the SC/ST category and take them out of the fold of affirmative action.

- Unequal Opportunities: The policy of protective and compensatory discrimination leads to disproportional representation of sub-castes in employment, education, and legislature.

- In Tamil Nadu, a 3% quota within the Scheduled Caste quota is accorded to the Arundhatiyar caste, after Justice M S Janarthanam report stated that despite being 16% of the SC population in the state, they held only 0-5% of the jobs.

- Graded Inequalities: There have been graded inequalities among SC communities and even among the marginalised, some communities have less access to basic facilities.

- The relatively more forward communities among them have managed to avail benefits consistently while crowding the more backward ones out.

- Overcoming Hierarchy: The SCs category is not homogenous and comprises a wide range of communities with distinct cultural, social, and economic characteristics.

- According to the annual report of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, there were 1,263 SCs in the country in 2018-19.

- Some SC communities may have made progress in education, employment, and socio-economic development, while others continue to face significant disadvantages.

- Securing Social Mobility: The reservation policy is ineffective in providing benefits to every sub-caste group at a uniform level which resulted in competition and conflict between various sub-caste groups of Scheduled Castes.

- The acquisition of political power, educational improvement, and occupational change could become the major assets for Scheduled Castes’ upward mobility, which acts as a major factor for the demand for sub-categorization.

- Ensuring Social Justice: Social justice emphasises ensuring that historically marginalised communities receive fair and just treatment and that their specific concerns are adequately addressed.

- Sub-categorization allows for a more targeted approach in addressing the specific vulnerabilities and needs of particular SC sub-groups.

- Ensuring Equitable Distribution of Resources: Sub-categorization could help avoid the concentration of benefits in certain communities while others remain underserved.

- For this, States have tried to divide the scheduled caste quota on the grounds that caste is a form of graded inequality.

- Punjab created an order of preferences in 1975 within scheduled castes for recruitment.

Challenges Related with Sub-Categorisation of Caste

Following are few challenges that need to be tackled, associated with sub-categorisation of castes:

- Identification and Criteria: Determining the criteria for sub-categorization can be challenging. Parameters such as socio-economic status, educational attainment, or regional factors may be considered, but reaching a consensus on these criteria can be difficult.

- Supreme Court rulings in 1976 and 2005 emphasises that ‘SCs are not castes, they are class’ and their protection is based on addressing untouchability, not other factors.

- Data Accuracy and Availability: Concrete population numbers of each community and sub-community and their respective socio-economic data are necessary to decide how castes can be categorised, how much percentage should be given, etc.

- Obtaining accurate and up-to-date data on the socio-economic status of different Scheduled Caste communities is a challenge.

- Potential for Intra-group Disputes: Sub-categorization may lead to internal divisions and disputes among SC communities.

- Some groups may feel marginalised from the benefits, leading to social tensions within the broader Scheduled Caste category.

- For instance, backwardness among SCs also draws from the practice of untouchability, and sub categorisation may sharpen differences within and bring in competitive affirmative action.

- Possibility of Fragmentation: There is a risk that sub-categorization might lead to the fragmentation of the SC community, diluting their political and social identity.

- This could weaken their collective strength in advocating for their rights.

- Quota May Not be Enough: The National Commissions for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes had opposed the move, arguing that just setting aside a quota within the quota would not be enough.

- They have argued that given the disparity, even if posts were reserved at higher levels, these most backward SCs would not have enough candidates.

- Thus, it needs to be made sure that the existing schemes and benefits reach them on a priority basis.

Way Forward

To gain positive achievement, following measures need to be taken:

- Exploring Alternatives to Introduce Sub-Categorisation: The Union government needs to explore legal options for the same.

- For instance, the Attorney General of India (AGI) had opined that a constitutional amendment could be brought in to facilitate this.

- The NCSC and NCST had opined that Article 16(4) of the Constitution already provided for States to create special laws for any backward classes it felt were under-represented.

- The Justice Usha Mehra Committee in its 2008 report recommended the inclusion of Clause (3) in Article 341 through a constitutional amendment empowering state legislature to enact reclassification of the Scheduled Caste category subject to Presidential confirmation.

- Data Collection and Analysis: According to legal experts, the Constitution does not prohibit the Parliament from sub-categorising SCs or STs.

- However, the government needs to ensure comprehensive and accurate data collection on the socio-economic conditions of different Scheduled Caste communities.

- This can be the only empirical basis to justify sub-categorisation of benefits and evaluating extra share of benefits required by each community.

- Criteria for Development: Develop transparent and inclusive criteria for sub-categorisation, considering factors such as socio-economic status, educational attainment, and regional disparities.

- The Andhra Pradesh government in 1996 formed a Commission of Justice Ramachandra Raju, which recommended sub categorisation of Scheduled Caste in the State based on evidence that some communities were more backward and had less representation than others.

- Following the Middle Path: Strike a balance between recognizing the diversity within the Scheduled Caste category and maintaining the overall unity of the community.

- Policies need to address the specific needs of sub-groups without causing fragmentation or weakening the collective strength of the SC community.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Classes

Constitutional Provisions to Support Weaker Sections

Following provisions of the Indian Constitution deals with the support and welfare of Weaker Sections:

- Article 15(4): The special provisions for their advancement.

- Article 16(4A): Speaks of reservation in the services under the State in favour of SCs/STs.

- Article 17: Abolishes Untouchability.

- Article 46: Requires the State to promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the SCs and STs, and to protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.

- Article 330 and Article 332: Provide for reservation of seats in favour of the SCs and STs in the House of the People and in the legislative assemblies of the States.

- Article 335: Provides that the claims of the members of the SCs and STs shall be taken into consideration, consistently with the maintenance of efficiency of administration, in the making of appointments to services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or of a State.

- Article 338: Provides for a National Commission for the Scheduled Castes (NCSC) and NCST.

- Part IX relating to the Panchayats and Part IXA of the Constitution relating to the Municipalities, reservation for SCs and STs in local bodies has been envisaged and provided.

About the Presidential List

The Central List of Scheduled Castes and Tribes is notified by the President under Articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution.

- Need for Parliament Consent: The consent of the Parliament is required to exclude or include castes in the List and the states cannot unilaterally add or pull out castes from the List.

- As per Article 341, those castes notified by the President are called SCs and STs.

- Variation Across States: A caste notified as SC in one state may not be a SC in another state.

- These vary from state to state to prevent disputes as to whether a particular caste is accorded reservation or not.

- No community has been specified as SC in Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland, and Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep.

State by State, Prominent Tribal & Dalit Communities

Following are few important Weaker Communities of the various States:

- Maharashtra: Mahar, Matang, Gond, Bhil, Dhule, etc.

- Rajasthan: Meghwal, Bairwa, Jatav, Meena, Bhil, etc.

- Odisha: Khond, Santal, Gond, Pan, Dom, Dhoba, Ganda, Kandra, Bauri, etc.

- Chhattisgarh: Gond, Kawar/Kanwar, Oraon, Bairwa, Raidas, etc.

- Madhya Pradesh: Balai, Bhil, Gond, etc.

- West Bengal: Rajbanshi, Matua, Bagdi, etc.

- Gujarat: Vankar, Rohit, Bhil, Halpati, etc.

- Assam: Bodo, Karbi, etc.

- Tripura: Debbarma community, Das, Badyakar, Shabdakar, Sarkar, etc.

- Uttarakhand: Harijan, Balmiki, Jaunsari, Tharu, etc.

|

![]() 3 Aug 2024

3 Aug 2024

On Applicability of ‘Creamy Layer’ Principle: Only the opinion of Justice Gavai bats for introducing the ‘creamy layer’ exception for SCs (and STs) that is already followed for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) as highlighted in Indra Sawhney Case.

On Applicability of ‘Creamy Layer’ Principle: Only the opinion of Justice Gavai bats for introducing the ‘creamy layer’ exception for SCs (and STs) that is already followed for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) as highlighted in Indra Sawhney Case.