India and Sri Lanka face long-standing disputes over fisheries in the Palk Strait and the sovereignty of Katchatheevu island, which, if handled prudently, could become symbols of regional cooperation rather than conflict.

Geographical Features of Katchatheevu

- Location: A 285-acre uninhabited island in the Palk Strait, lies strategically between India and Sri Lanka.

- Proximity: 33 km from the Indian coast (Rameswaram), 62 km from Jaffna (Sri Lanka), and 24 km from Delft Island (Sri Lanka).

- Size: 1.6 km in length and 300 m at its widest point.

- Habitation: No drinking water sources; unsuitable for permanent settlement.

- Religious Linkages: Houses St Anthony’s Church (early 20th century), which hosts an annual festival attended by devotees from both India and Sri Lanka.

Historical Background

- Geological Origin: Formed by a volcanic eruption in the 14th century.

- Early Control: Initially under the Jaffna kingdom (Sri Lanka); later passed to the Ramnad zamindari (Tamil Nadu region).

- Colonial Disputes: Both British India and British Ceylon claimed the island in 1921 to settle fishing boundaries. A survey placed it under Ceylon, but Indian claims citing Ramnad control persisted. The dispute continued even after Indpendence until 1974.

- 1974 Agreement (Indira Gandhi–Sirimavo Bandaranaike): Recognised Katchatheevu as part of Sri Lanka.

- 1976 Agreement: Established exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in the Gulf of Mannar and Bay of Bengal. Both sides agreed not to fish in each other’s waters.

India–Sri Lanka Maritime Boundary Agreement, 1974 : Key Provisions

- Article 4 – Sovereignty: Each country would exercise sovereignty, exclusive jurisdiction, and control over waters, islands, continental shelf, and subsoil falling on its respective side of the boundary.

- Article 5 – Kachchativu Access: Although sovereignty over Kachchativu island went to Sri Lanka, Indian fishermen and pilgrims retained access rights to visit for purposes such as the annual St. Anthony’s festival without travel documents or visas.

- Article 6 – Traditional Rights: Vessels of both countries would enjoy traditional rights in each other’s waters.

- Article 7 – Shared Resource Exploitation: If a geological resource deposit (petroleum, natural gas, minerals) extended across the boundary, both countries would reach agreement on joint exploitation and apportionment of proceeds.

|

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Framework:

- The 1974 and 1976 agreements between India and Sri Lanka delimit the maritime boundary in accordance with the UNCLOS.

- Equidistance principle: Maritime boundaries are generally determined by the equidistance principle, which requires drawing a median line equidistant from the coasts of the two states.

- Adjusted Equidistant Line: In the 1974 Agreement, instead of a strict median line, an adjusted equidistant line was drawn, wherein certain maritime spaces were granted to one party for the benefit of the other.

- By this adjustment, Katchatheevu Island fell on the Sri Lankan side of the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL).

- Both countries subsequently notified the agreements under UNCLOS.

|

Why the Issue Persists

Despite legal clarity, practical challenges continue:

- Fisheries Dependence: Tamil Nadu fishermen, facing depleted stocks on the Indian side, cross into Sri Lankan waters.

- Bottom Trawling: Destructive practices by Indian mechanised trawlers harm marine ecosystems and affect Sri Lankan Tamil fishermen.

- Post–Civil War Enforcement: With stronger Sri Lankan naval patrols after 2009, arrests and deaths of Indian fishermen have become frequent, fuelling domestic political anger in Tamil Nadu.

- Spike in arrests: In 2024, the Sri Lankan Navy arrested 528 Indian fishermen, highlighting a significant spike compared to previous years.

- Deaths at Sea: According to Ministry of External Affairs, 5 Indian fishermen had died in Sri Lankan waters during 2021 and 2 in 2024

- Domestic Pressures: Tamil Nadu State assembly and leaders across parties have repeatedly demanded retrieval of Katchatheevu and filed petitions in the Supreme Court.

Bottom Trawling Problem

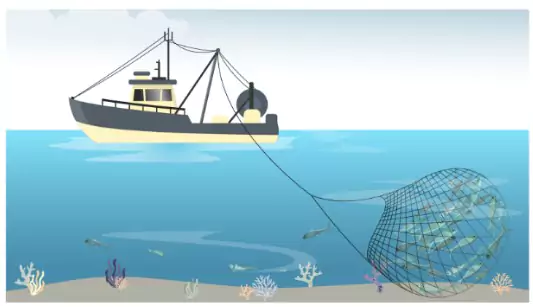

- Destructive Fishing Practice: Indian mechanised trawlers engage in bottom trawling, which involves scooping the seabed and causes severe damage to marine biodiversity.

- Historical Promotion: The method was actively encouraged in India between the 1950s and 1970s, with Norwegian assistance, to enhance seafood exports.

- Resource Depletion: Overexploitation of marine resources on the Indian side has pushed fishermen to cross into Sri Lankan waters in search of better catch.

- Regulatory Measures: Sri Lanka banned bottom trawling in 2017. India had also agreed in 2016 to phase out the practice, but enforcement has remained weak and inconsistent.

What is Bottom Trawling?

Bottom trawling is a fishing practice in which large, mechanised trawlers drag heavy nets fitted with rollers or weights along the seabed. The nets scoop up everything in their path, including fish, shellfish, and other marine organisms.

Impact of Bottom Trawling

- Marine Biodiversity Loss: The practice indiscriminately captures both target and non-target species, leading to overfishing and destruction of fragile ecosystems such as coral reefs and seagrass beds.

- Habitat Destruction: Continuous scraping of the seabed damages spawning grounds, nurseries, and benthic habitats, threatening long-term fish productivity.

- Livelihood Concerns: Depletion of marine resources reduces the catch for traditional and artisanal fishermen, aggravating conflicts, especially in sensitive areas like the India–Sri Lanka Palk Bay region.

- Carbon sequestration: Stirring up sediments releases stored carbon, contributing to ocean pollution and undermining marine climate resilience.

|

| PW OnlyIAS Extra Edge

International Laws on Freedom of Fishing

- High Seas Freedom: Article 87 grants all states the freedom of fishing on the high seas, beyond national jurisdiction; exercised with due regard for the interests of other states and international law.

- Conservation Duties: States to cooperate in the conservation and management of living resources on the high seas; States must adopt measures to prevent overfishing, overexploitation, and ensure sustainability.

UN Fish Stocks Agreement (1995)

- Supplements UNCLOS by providing a framework for the conservation and sustainable use of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks.

|

Tamil Nadu’s Position on Katchatheevu

- Initial Opposition: Indira Gandhi’s move faced protests for bypassing the state assembly and ignoring Ramnad zamindari’s historical control.

- 1991 Resolution: TN Assembly sought retrieval of Katchatheevu and restoration of fishermen’s rights after India’s failed Sri Lanka intervention.

- Legal Litigation:

-

- 2008: J. Jayalalithaa petitioned the Supreme Court, arguing that ceding territory required a constitutional amendment.

- 2011: As CM, she passed a fresh resolution in the state assembly and moved the SC again, citing increasing arrests of fishermen.

Government of India’s Stand on Katchatheevu

- Disputed Territory: The Union Government argued that Katchatheevu had always been under dispute; hence, no Indian territory was ceded nor sovereignty relinquished.

- Through 1974 & 1976 Agreements, Katchatheevu was placed on the Sri Lankan side of the International Maritime Boundary Line.

- 2022 Statement in Rajya Sabha: Reiterated that Katchatheevu lies on the Sri Lankan side of the IMBL, retrieval of the island was “impossible” and noted that the matter remains sub-judice before the Supreme Court.

Significance of Katchatheevu

- Geopolitical Dimension

- Palk Strait is a strategic chokepoint, connecting the Bay of Bengal with the Indian Ocean.

- The issue tests India’s Neighbourhood First Policy and ability to counter Chinese influence in Sri Lanka.

- Economic Dimension

- Rich in fish, prawns, and aquatic resources, the region sustains thousands of fisherfolk families in Tamil Nadu.

- Overfishing and destructive methods threaten the Blue Economy vision and long-term sustainability.

- Security Dimension

- Illegal crossings complicate maritime security, with risks of smuggling, piracy, and infiltration (LTTE legacy).

- India must balance fisherfolk rights with broader coastal security imperatives.

- Legal Dimension

- Agreements of 1974 & 1976 are binding treaties under international law and registered with the UNCLOS framework.

- Any unilateral withdrawal would erode India’s treaty credibility, impacting future maritime negotiations.

- Humanitarian & Political Dimension

- Arrests and custodial violence against fishermen generate human rights concerns.

- The dispute is politically sensitive in Tamil Nadu, where livelihood, cultural ties, and identity issues converge.

The Real Issue: Fisheries Management, Not Sovereignty

- Katchatheevu’s sovereignty is settled, but fisheries governance remains unresolved.

- The conflict lies in unsustainable practices, lack of alternative livelihoods, and inadequate bilateral cooperation mechanisms.

Way Forward

- Sustainable Fisheries Management

- Ban Destructive Practices: Strictly enforce India’s commitment to phase out bottom trawling.

- Introduce Alternatives: Promote trawl-to-tuna conversion, deep-sea fishing, and sustainable gear.

- Bilateral Cooperation

- Time/Quota Sharing Models: Inspired by Baltic Sea Fisheries Convention, create seasonal quotas or rotational fishing days in Palk Bay.

- Joint Research Stations: Establish a marine monitoring centre on Katchatheevu to build scientific cooperation.

- Institutional Dialogue: Strengthen the India–Sri Lanka Joint Working Group on Fisheries.

- Economic & Livelihood Measures

- Deep-Sea Fishing Transition: Provide subsidies, credit, and training for fisherfolk to move beyond near-shore waters.

- Joint Ventures: Encourage Indo–Sri Lankan Tamil fishing cooperatives.

- Blue Economy Focus: Link fisherfolk welfare to India’s Blue Economy 2030 Roadmap.

- Diplomatic Initiatives

- Leverage Neighbourhood First & SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) for cooperative maritime governance.

- Ensure that the issue does not derail broader economic and security cooperation with Sri Lanka (energy, ports, trade).

- Federal Cooperation:

- Involve Tamil Nadu government in negotiations, ensuring cooperative federalism and reducing Centre–State friction.

Models for Cooperation

- Baltic Sea Fisheries Convention: Equitable quota-sharing.

- Norway–Russia Fisheries Treaty: Joint management of overlapping resources; managing shared fish stocks in the Barents Sea.

- India–Bangladesh (2015 Land Boundary Agreement): Demonstrates India’s ability to settle disputes peacefully while balancing domestic concerns.

|

Conclusion

The Katchatheevu sovereignty issue is settled, but the fisheries dispute remains alive due to ecological, economic, and political pressures. Reopening old treaties would damage India’s international credibility, but ignoring fisherfolk distress risks domestic instability. The solution lies in sustainable fishing practices, cooperative mechanisms, and livelihood diversification.

If approached pragmatically, the Palk Strait can transform from a line of division into a bridge of cooperation, strengthening both India–Sri Lanka ties and the regional vision of SAGAR and the Blue Economy.

![]() 13 Sep 2025

13 Sep 2025