![]() 19 Jul 2024

19 Jul 2024

European colonial forest laws drastically altered the life of Colonies. By transforming forests from community resources into state-controlled commodities, these rules disrupted livelihoods, marginalized Indigenous communities, and laid the foundation for ongoing environmental challenges.

Shifting Cultivation: One of major impacts of European colonialism was on practice of shifting cultivation or swidden agriculture.

Criminalizing Subsistence Hunting: Customary practice of hunting deer, partridges, and a variety of small animals by people who lived in or near forests for survival was prohibited by forest laws.

Shift from Subsistence to Trade: After the forest department took control of the forests, many communities left their traditional occupations and started trading in forest products.

Indigenous Trade Networks: In India, from medieval period onwards, we have records of Adivasi communities trading elephants and other forest goods like hides, horns, silk cocoons, ivory, bamboo, spices, fibers, grasses, gums, and resins through nomadic communities like the Banjaras.

Indigenous Trade Networks: In India, from medieval period onwards, we have records of Adivasi communities trading elephants and other forest goods like hides, horns, silk cocoons, ivory, bamboo, spices, fibers, grasses, gums, and resins through nomadic communities like the Banjaras.

In many parts of India, and across the world, forest communities rebelled against the changes that were being imposed on them. The leaders of these movements against the British were Siddhu and Kanu in Santhal Parganas, Birsa Munda of Chhotanagpur, or Alluri Sitarama Raju of Andhra Pradesh.

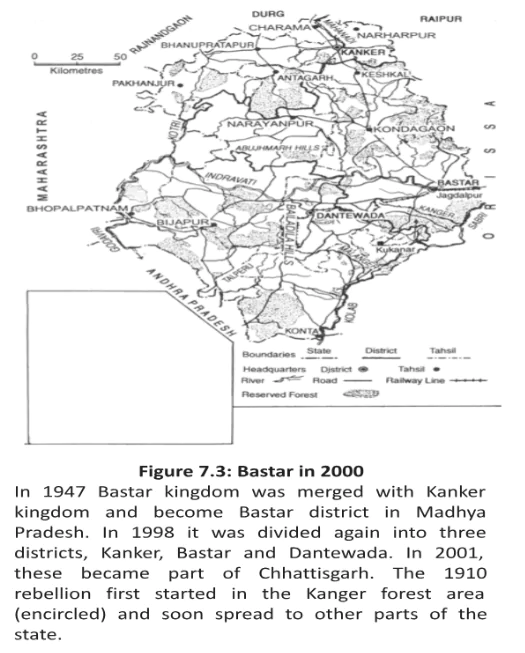

Growing Resentment: When the colonial government proposed to reserve 2/3rd of forest in 1905 and stop shifting cultivation, hunting, and collection of forest produce, people of Bastar were very worried.

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

While aiming for ‘scientific forestry‘, colonialism sowed seeds of environmental and social conflicts that persist today. After Independence, the same practice of keeping people out of forests and reserving them for industrial use continued. In the 1970s, the World Bank proposed that 4,600 hectares of natural sal forest should be replaced by tropical pine to provide pulp for the paper industry. It was only after protests by local environmentalists that the project was stopped.

| Related Articles | |

| WORLD BANK | European Parliament Elections |

| ENVIRONMENT | Mughal Painting |

<div class="new-fform">

</div>