The High Seas Treaty, formally known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, will come into force in January 2026.

Background of BBNJ Agreement

- The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 1982 did not adequately address biodiversity protection beyond national boundaries.

- To bridge this gap, the UN General Assembly created an ad hoc working group in 2004.

- Between 2018 and 2023, four rounds of Intergovernmental Conferences negotiated the treaty, which was adopted in June 2023.

About the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ Agreement)

- Purpose: To establish a comprehensive framework for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (the “high seas”).

- Legal Basis: It is an international treaty under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

- It is the first legally-binding international agreement safeguarding marine life in the High Seas.

Signing & Ratification

- Implementation: The treaty would become international law 120 days after at least 60 countries submit their formal ratification documents

- Global Status: As of 1st November 2025, 145 countries have signed the High Seas Treaty.

- Ratification: So far,75 countries have ratified it.

- India’s Position: India signed the treaty in 2024, but has not yet ratified it.

What are High Seas?

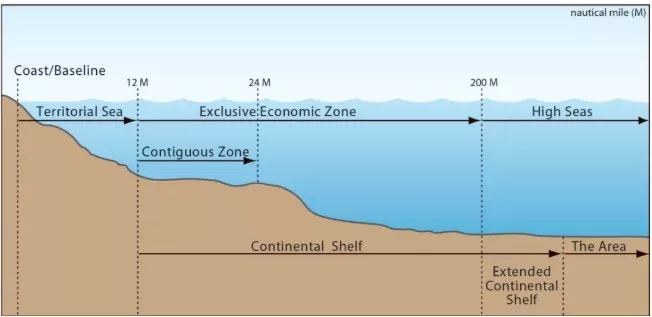

- According to the 1958 Geneva Convention, high seas are ocean areas lying beyond the jurisdiction of any state.

- They extend past a nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which typically reaches 200 nautical miles from its coast.

- Governed by principles of freedom of navigation, overflight, fishing, and scientific research.

Significance of High Seas

- Vast Coverage: Covers more than 64% of the oceans and 43% of Earth’s surface, hosting nearly 2.2 million marine species and trillions of microorganisms.

- Environmental Regulator: Absorb 25% of global CO₂, produce half of the world’s oxygen, and balance the climate by distributing heat.

- Resource Reservoir: Provide seafood, minerals, genetic resources, and medicinal compounds vital for human use.

- Biodiversity Hub: Support rich marine life, including species still unknown to science.

- Challenges: Lack of ownership leads to overfishing, biodiversity loss, plastic dumping (17 million tonnes in 2021), acidification, and pollution.

|

Pillars of the High Seas Treaty

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs):

- Legal framework for creating MPAs; previously only 1.45% of high seas were protected.

- Key mechanism for achieving the “30×30” goal of protecting 30% of oceans by 2030.

- Marine Genetic Resources (MGR), including the fair & Equitable Sharing of Benefits

- Treaty governs MGRs in international waters, including Digital Sequence Information (DSI).

- Benefit-sharing includes monetary contributions (based on national income) and non-monetary transfers like technology sharing, capacity building, and joint research.

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs):

- Comprehensive EIAs required for activities with potential significant impact in international waters.

- The process covers screening, scoping, assessment, public notification, and monitoring.

- Applies to national and international activities affecting high seas.

- Integrates Indigenous and traditional knowledge with scientific methods.

- Capacity Building & Technology Transfer:

- Establishes training programs, research fellowships, and institutional partnerships.

- Develops regional hubs for marine technology, fostering collaboration and local capacity.

- Ensures developing nations can participate meaningfully in high-seas governance.

Key Challenges

- Ambiguity Between “Common Heritage” and “Freedom of the High Seas”

- The treaty attempts to balance two contradictory principles:

- Common Heritage of Humankind: All nations should have equitable access and share benefits from marine resources.

- Freedom of the High Seas: States enjoy unrestricted rights for navigation, research, and resource use.

- The partial application of the common heritage principle to MGRs reflects a compromise rather than a resolution, creating uncertainty in research rights and profit-sharing.

- Governance and Benefit-Sharing of Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs)

- Earlier, the governance of MGRs was undefined, raising fears of biopiracy and monopolisation by developed nations.

- While the treaty proposes a framework for monetary and non-monetary benefit-sharing, it lacks clarity on:

- How benefits will be calculated and distributed.

- The mechanism for monitoring compliance.

- Developing countries fear being excluded from scientific and commercial gains, continuing global inequities.

- Limited Participation of Major Powers

- The non-ratification by the United States, China, and Russia—three key maritime powers—poses a major risk to the treaty’s success.

- Without their participation, enforcement, funding, and monitoring mechanisms may remain weak.

- Their absence also reduces geopolitical legitimacy, undermining collective governance of global commons

- Overlap with Existing Multilateral Institutions

- The BBNJ framework must coexist with other international organisations such as:

- International Seabed Authority (ISA) – regulates mineral resources.

- Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) – oversee fisheries.

- The challenge lies in avoiding jurisdictional overlap and ensuring policy coherence, as multiple regimes could lead to fragmentation of ocean governance and legal disputes.

- Implementation and Monitoring Difficulties

- Establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) on the high seas requires global coordination, monitoring, and enforcement, which is logistically complex and costly.

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) depend on scientific data-sharing, which many countries may lack the capacity or willingness to provide.

- Dynamic ocean management is required, as marine ecosystems evolve due to climate change, demanding continuous review mechanisms.

Way Forward

- Clarify Legal Ambiguities: The treaty must clearly define benefit-sharing mechanisms, jurisdictional overlaps, and liability provisions.

- Encourage Universal Ratification: Diplomatic efforts should focus on bringing major powers into the framework.

- Build Institutional Synergy: Strengthen coordination with UNCLOS, ISA, RFMOs, and other UN agencies.

- Enhance Scientific Capacity: Support developing nations with technology transfer, data-sharing, and marine research funding.

- Adopt Adaptive Management: Implement real-time monitoring and dynamic MPAs to respond to changing oceanic conditions.

![]() 4 Nov 2025

4 Nov 2025