Amid rising human–wildlife conflict, Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav chaired high-level National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and Project Elephant meetings at Sundarbans Tiger Reserve, West Bengal to review conservation strategies and conflict mitigation.

Key Highlights of the Meet

- Strengthening Science-Based Conservation: The Minister emphasised scientific management, landscape-level planning and evidence-based interventions as pillars of India’s globally recognised tiger conservation model.

- Focus on Human–Wildlife Conflict: The NTCA reviewed a three-pronged strategy to address human–tiger conflict, including the dedicated initiative Management of Tigers Outside Tiger Reserves (TOTR).

- Expansion of Flagship Projects: Decisions were ratified on expanding Project Cheetah to Gandhisagar Wildlife Sanctuary and Banni grasslands, alongside tiger translocation and prey augmentation plans.

- Elephant Conservation & Inter-State Coordination: Project Elephant reviewed human–elephant conflict, compensation mechanisms, elephant corridor protection, and prioritised coordinated inter-State action in southern and northeastern India.

- Monitoring, Capacity Building & Global Engagement: Progress under the sixth cycle of All India Tiger Estimation, CAMPA-supported initiatives, staff training, and international cooperation with African countries was assessed, alongside preparations for the Global Big Cat Summit.

Tigers Outside Tiger Reserves (TOTR)

- TOTR is a national-level initiative by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

- Implementation: The project will be implemented over 2025–28, with a total outlay of ₹88.7 crore.

- It will be coordinated centrally by NTCA and executed through state forest departments.

- Pilot phase: In 80 forest divisions across 10 states, identified initially on the basis of data of recurring human-tiger conflict.

- Conflict Mitigation Focus: To systematically reduce human–tiger conflict in non-reserve landscapes through early warning systems, rapid response teams and community-based conflict management.

- Landscape-Level Coexistence: By adopting a landscape approach, TOTR balances ecological sustainability with human safety and livelihoods, integrating conservation into human-dominated regions.

|

What is Human–Wildlife Conflict?

- Human–Wildlife Conflict refers to struggles that arise when the resource requirements of wildlife overlap with those of human populations.

- It involves interactions that result in negative impacts on people, their resources, or wild animals and their habitats.

Causes of Human–Wildlife Conflict

- Habitat Fragmentation: Deforestation, mining, roads and railways disrupt wildlife habitats and corridors, forcing animals into human settlements.

- Agricultural Expansion: Cultivation near forests attracts crop-raiding species like elephants, wild boars, and nilgai.

- Infrastructure Development: Linear infrastructure (railways, highways, canals) cuts across animal movement routes, increasing accidents.

- Over 150 elephant corridors in India are intersected by around 700 railway tracks and highways, forcing animals into human settlements.

- Climate Change: Altered rainfall and food scarcity push animals to seek resources outside forests.

- Population Pressure: Rising human population around protected areas increases competition for land and water.

Decline of Prey Base: Reduced natural prey compels predators like tigers and leopards to attack livestock or humans.

Impact of Human–Wildlife Conflict

Impact on Humans

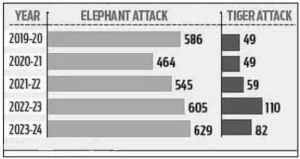

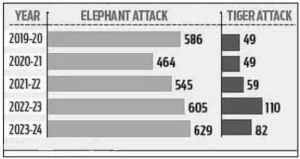

- Loss of Life and Injury: India reports hundreds of deaths annually from elephant, tiger, leopard, and snake encounters.

- Between 2019 and 2022, over 1,500 people were killed by elephants in India.

- Economic Losses: Crop damage, livestock predation, and property destruction disproportionately affect marginal farmers.

- Livelihood Insecurity: Repeated losses deepen rural poverty and indebtedness.

For example, Maharashtra suffers an annual agricultural loss ranging from Rs 10,000 crore to Rs 40,000 crore because of human-wildlife conflict involving herbivores

For example, Maharashtra suffers an annual agricultural loss ranging from Rs 10,000 crore to Rs 40,000 crore because of human-wildlife conflict involving herbivores

- Psychological Trauma: Fear, stress, and long-term anxiety among communities living near forests.

- The mental health of residents living on the frontlines of human-tiger conflicts is severely impacted as seen in people around Sunderban.

- Zoonotic Disease Risk: Increased human–wildlife interaction raises zoonotic disease threats.

- Kerala witnessed a Nipah virus outbreak linked to fruit bats, highlighting public health risks of ecological disturbance.

- Social Unrest: Rising anger leads to protests and erosion of trust in governance.

- Shimla Nagrik Sabha staged a protest demanding immediate action against the growing menace of stray dogs and monkeys in the city.

Impact on Animals

- Retaliatory Killings: Villagers often use poisoned carcasses or “avuttukaay” (crude explosive baits) to kill leopards and wild boars in revenge for livestock or crop loss.

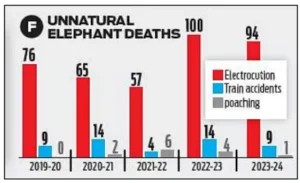

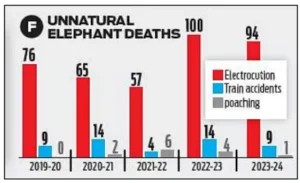

- Accidental Mortality: Electrocution via sagging power lines or illegal fences killed nearly 500 elephants between 2018 and 2023.

- Genetic Isolation: Animals afraid to cross roads or fences become isolated in small forest patches, leading to inbreeding and long-term population decline.

- Due to this isolation, the entire Asiatic lion population has an extremely low genetic diversity making them more susceptible to diseases and genetic abnormalities, and less able to adapt to environmental changes.

- Behavioral Shifts: Continuous negative interactions make animals more aggressive and “habituated” to human presence, increasing the likelihood of future attacks.

- A leopard in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh, was beaten to death by villagers in retaliation after it killed a local resident.

Provisions and Initiatives to Curb Human–Wildlife Conflict in India

- Legal Provisions

-

- Wildlife Protection Act (WPA), 1972: Provides for the declaration of “vermin” in specific areas and empowers Chief Wildlife Wardens to manage conflict-prone animals.

- The Central Government can declare any wild animal (except those in Schedule I/Part II of Schedule II) as vermin for a specified area and time, essentially making them unprotected.

- Disaster Management Act, 2005: Allows states (like Kerala) to declare conflict as a state-specific disaster, enabling faster relief, compensation, and decisive action.

- Wildlife Protection (Kerala Amendment) Act, 2025, allows the Chief Wildlife Warden to order immediate culling or capture of animals like elephants, wild boars, and macaques attacking humans in residential areas.

- It bypasses the central law delays, and potentially declaring certain populations like wild boars as “vermin”.

- Institutional Measures:

- NTCA: It implements strategies such as “Tigers Outside Tiger Reserves” to reduce the impact of tigers on humans in places with recurring incidents of Tiger human Conflict.

- Project Elephant (1992): Focuses on corridor protection, mitigation of human–elephant conflict, and compensation mechanisms.

- RE-HAB Project: Reducing Elephant-Human Attacks using Bees ( RE-HAB) is a Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) initiative using “bee-fences” to prevent human-elephant conflict by deterring elephants with honeybees

- It is a cost-effective, harmless method that also boosts farmer income through honey production

- Compensation & Insurance: Ex-gratia payments for human death, injury, crop and livestock loss.

- Recent expansion of PM Fasal Bima Yojana allows states to include “wild animal damage” as a localized risk for insurance claims.

- The Supreme Court mandated ₹10 lakh ex gratia compensation for each human death caused by wildlife under the MoEF&CC’s Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats scheme.

- Technology & Planning: AI-based early warning systems, radio-collaring, camera traps, and GIS-based conflict hotspot mapping.

- AI-Based Warning Systems: The Northeast Frontier Railway uses “Gajraj,” an AI-based system to detect elephants near tracks.

- Radio-Collar Monitoring: Used for real-time tracking of “rogue” elephants or tigers to provide early warnings to villages.

Global Practices of Human-Wildlife Coexistence

- India (Bishnoi Community): For centuries, the Bishnois of Rajasthan have protected Blackbucks and Chinkaras as sacred, even nursing orphaned fawns.

- Amazon (Indigenous Territories): Tribes like the Kayapo use traditional zoning to maintain “buffer forests” that separate hunting grounds from village settlements.

- Africa (Maasai ‘Lion Guardians’): In Kenya, former lion hunters are now employed as “Guardians” who use traditional tracking skills to warn herders of lions, reducing retaliatory killings.

- Bhutan (Gross National Happiness): State-sponsored “Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Strategy” includes spiritual compensation, viewing coexistence as a religious duty.

- Sri Lanka (Village Fencing): Community-managed electric fences surrounding entire villages, rather than individual farms, have proven more effective for elephant coexistence.

|

Ways to Mitigate Human–WildlifeConflict

- Smart Infrastructure: Constructing dedicated underpasses and overpasses.

- For example, the NH-44 stretch through Pench Tiger Reserve features eco-ducts that allow tigers to pass safely.

- Early Warning Systems (EWS): Utilizing AI-powered cameras and SMS alerts.

- A red-light alert system and bulk SMS service pioneered by the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) have reduced elephant-related human fatalities to near zero in Tamil Nadu’s Valparai plateau.

- Non-Lethal Deterrents: Using bio-fencing (chili-tobacco fences) or acoustic devices that mimic the sound of bees or tigers to keep herbivores away from crops.

- “Digital beehives,” which are acoustic devices designed to reproduce the sounds of aggravated bees, are being used in the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve (MTR), Nilgiri, TamilNadu as an elephant deterrent

- Community-Led Conservation: Recruiting “Primary Response Teams” (PRTs) from local villages who are trained and equipped to manage crowds and track animals until forest officials arrive.

- Restoring Natural Fodder: Active removal of invasive weeds like Lantana and planting native bamboo and grasses within core forest areas to keep animals away from forest fringes.

Conclusion

Human–wildlife conflict demands science-based, community-led, and landscape-level solutions, balancing human safety, livelihoods, and biodiversity conservation through coordinated governance, technology, and coexistence-oriented policies.

![]() 25 Dec 2025

25 Dec 2025

For example, Maharashtra suffers an annual agricultural loss ranging from Rs 10,000 crore to Rs 40,000 crore because of human-wildlife conflict involving herbivores

For example, Maharashtra suffers an annual agricultural loss ranging from Rs 10,000 crore to Rs 40,000 crore because of human-wildlife conflict involving herbivores