How to Approach the Essay?

|

In the early 20th century, Indian villages functioned as tightly-knit social units. The panchayat not only governed but also acted as a hub for dispute resolution, mutual aid, and cultural continuity. This interconnectedness fostered resilience even during crises—like droughts or communal tensions—because people relied not just on systems, but on each other. This invisible yet vital force is known as social capital signifying the networks of trust, reciprocity, and civic engagement that bind communities together. It manifests in acts as small as neighbours watching over each other’s children or as large as citizens uniting for public welfare. Social capital enhances not only emotional well-being but also democratic participation, safety, and even economic mobility.

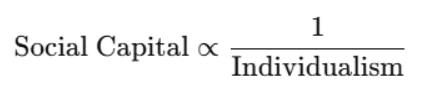

Yet today, these connections are weakening. As urban life accelerates and individualism becomes a dominant cultural ethos, the age-old norms of mutual obligation are under strain. The essay explores this tension—how rising individualism challenges social capital, what we lose in the process, and how we might reimagine community bonds for the 21st century.

To understand what we’re losing, we must first grasp what social capital has historically offered. It facilitates cooperation, reduces transaction costs, and promotes shared norms that make communities livable. From Maharashtra’s rural cooperatives to Delhi’s mohalla sabhas, societies rooted in social trust are more resilient, inclusive, and adaptive.

This communal trust enhances diverse domains of life. In education, high-social-capital environments show better outcomes not just due to material inputs but because of collective accountability. Kerala’s library networks and reading campaigns are sustained not just by government grants but by volunteerism and shared cultural pride.

Economically, social capital translates into tangible support structures. Self-help groups (SHGs) in states like Tamil Nadu or Andhra Pradesh offer microcredit, but more importantly, they foster empowerment through solidarity. Financial cooperation, leadership, and group accountability emerge naturally from strong social ties.

Beyond economic and civic domains, social capital also nurtures a sense of psychological security. Knowing one belongs to a trusted web of relationships reduces stress, improves emotional regulation, and even correlates with longer life expectancy. Communities where elders, youth, and women feel valued tend to have lower crime rates and higher well-being.

Religious and cultural institutions historically played a key role in nurturing social capital. Temples, gurudwaras, mosques, and churches often acted as centers of aid, counseling, and social bonding. Langars in Sikh communities, for instance, represent both spiritual and social solidarity—feeding thousands irrespective of caste or class.

Democratic governance also thrives under high social capital. Movements like the RTI in India or anti-corruption platforms in Latin America gained traction through grassroots mobilization, trust networks, and shared civic identity—not merely legislative backing.

But as these structures show, social capital is contextually embedded. It depends on community density, shared histories, and daily interaction. The question, then, is: what happens when these traditional conditions erode under the pressures of modern individualism?

The modern era has seen a growing emphasis on personal autonomy and self-definition, fundamentally reshaping how individuals relate to society. Urbanization, widespread use of digital platforms, and the spread of neoliberal values have empowered people to prioritize personal freedom, identity, and self-expression. This shift has challenged traditional social structures and norms that were often restrictive and oppressive. For example, women in urban India increasingly assert their independence, making choices about education, careers, and relationships that were previously constrained. Similarly, LGBTQ+ communities have found solidarity and support through online platforms, enabling them to live more openly.

Individualism has enabled people to move beyond rigid family, caste, or community expectations, fostering mobility and diverse lifestyles. Consumer culture simultaneously reinforces this trend by targeting individuals rather than communities. Customized entertainment options, personalized advertising, and private services focus on individual preferences, often at the expense of collective experiences.

The rise of the gig economy and remote work provides workers with flexibility but also fragments traditional professional networks, reducing face-to-face interactions and shared experiences such as lunch breaks or informal conversations. Even physical living environments have transformed; gated communities and urban housing complexes emphasize privacy and security but reduce opportunities for spontaneous neighborly interactions and communal living.

While individualism has brought greater freedom and choice, it has also weakened the social bonds and networks that constitute social capital. Technology connects people across distances but often fosters surface-level relationships rather than deep, trusting connections. Social media platforms tend to encourage curated, performative interactions, where vulnerability is rare and relationships are more about appearance than authentic connection. This shift results in a decline in traditional forms of community engagement, such as participation in festivals, rituals, and neighborhood gatherings, which historically reinforced trust and cooperation.

Workplaces, once vital spaces for social interaction and community building, now often mirror the isolation seen in personal life. Remote work and contractual jobs reduce continuous, meaningful interactions among colleagues, weakening a key source of social capital that helped compensate for eroding family ties. Similarly, urban spaces, designed for efficiency and privacy, encourage transactional and minimal contact, leading to feelings of isolation despite physical proximity. These changes disrupt the social ecosystems where cooperation, mutual support, and collective problem-solving thrived, posing challenges to social cohesion and communal resilience in today’s highly individualistic societies.

When social capital erodes, its absence impacts society beyond personal relationships, affecting structural and institutional dimensions. Civic disengagement increases significantly, as seen in declining voter turnout, widespread apathy toward local governance, and growing distrust in public institutions. Without strong networks of mutual concern and accountability, individuals lose both their voice and sense of responsibility in public affairs, weakening democratic participation and community decision-making.

The mental health consequences are deeply troubling. In rapidly growing urban centers like Bengaluru and Mumbai, loneliness has shifted from being an occasional experience to a pervasive norm. The rise of nuclear families, single-person households, and remote work cultures isolates individuals in ways that traditional extended family systems once prevented. This social isolation contributes to stress, anxiety, and depression, undermining overall well-being.

Social unrest becomes more frequent in fragmented societies lacking empathy and shared social norms. In these contexts, digital hate speech, communal polarization, and violent street clashes find fertile ground to spread. Without the “cushion” of trust and open dialogue that social capital provides, societies become brittle and fracture easily under social or economic pressures.

From an economic perspective, weaker social capital worsens inequality. Marginalized and vulnerable groups, without access to networks or community resources, face barriers in obtaining quality jobs, healthcare, and mentorship opportunities. As a result, social mobility increasingly depends on one’s inclusion in well-connected elite circles, further deepening divides.

Public goods and communal resources suffer greatly as well. The maintenance of clean public spaces, safe neighborhoods, and effective policing depends on collective vigilance and informal social monitoring. When social capital declines, people withdraw into private solutions—opting for gated security, bottled water, or private schooling—further eroding the public realm and reducing shared responsibility for community welfare.

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly exposed these vulnerabilities. The mass migration of workers walking hundreds of kilometers to their rural homes revealed the fragile nature of urban social support systems. Migrants lacked local anchoring, social networks, or community support in cities, making survival and resilience extremely precarious. This crisis underscored how critical social capital is—not just for social cohesion but for basic human survival.

The challenge facing societies today is not to revert to past models of tightly knit communities but to reimagine social capital in a world where individualism is deeply ingrained and unlikely to fade. The goal is to develop meaningful connections that respect personal autonomy and freedom, creating what sociologists call “networked individualism”, a state where individuals remain independent yet embedded in supportive social networks. This new form of social capital balances the desire for self-expression with the human need for belonging and cooperation.

While technology is often criticized for contributing to social fragmentation, it also holds tremendous potential to build new kinds of communities. Civic technology platforms such as IChangeMyCity enable citizens to report issues and collaborate with local authorities, turning passive users into active participants in improving their neighborhoods. Similarly, apps like Nextdoor facilitate communication among neighbors, organizing events, sharing resources, and fostering trust in local areas. These digital forums act as bridges between virtual connectivity and real-world engagement, helping rebuild social capital in innovative ways.

Education plays a crucial role in cultivating the foundations of social capital for future generations. Programs like Delhi’s Happiness Curriculum and Maharashtra’s social-emotional learning initiatives introduce children to concepts such as emotional intelligence, empathy, cooperation, and compassion from an early age. These curricula aim to develop social skills and community awareness, planting seeds for stronger social bonds and collective responsibility that will be essential in an increasingly individualistic society.

Urban design also needs to adapt to encourage social interaction in the modern context. Thoughtfully designed public spaces such as parks, libraries, and pedestrian-friendly zones provide venues for casual encounters and community-building. Events like Raahgiri Day in Gurugram, where city roads are temporarily closed to vehicles and opened to pedestrians, cyclists, and performers, exemplify how even in highly individualistic, urban environments, people can be brought together to reclaim communal spaces and foster shared experiences.

Workplaces represent another critical arena for nurturing social capital. Moving beyond purely competitive and transactional environments, organizations can cultivate inclusive HR policies, mentorship programs, and cultures of emotional openness. Such initiatives transform offices from isolated silos into communities of support, where employees feel valued and connected. Humanizing the modern economy by fostering genuine relationships at work is essential for building resilience and solidarity in the digital age.

Cultural renewal remains a vital ingredient in rebuilding social capital. Contemporary festivals, public art installations, and storytelling projects serve to rekindle collective memory and civic pride—especially in fast-changing urban landscapes. Events like Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda Festival or the Kochi-Muziris Biennale attract diverse communities, create shared cultural experiences, and offer emotional spaces where people can connect over a common heritage. These initiatives help nurture a sense of belonging and identity, which are foundational to social cohesion.

Social capital and individualism are two sides of the same coin, representing opposing yet complementary forces that together shape the fabric of society. Just as democracy balances individual rights with collective duties, a healthy society must balance personal autonomy with a sense of belonging and affiliation. When individuals are able to flourish within networks of trust, cooperation, and mutual support, the entire community benefits holistically, fostering resilience and shared prosperity.

In today’s world, marked by increasing digital alienation, sprawling urban landscapes, and rising mental health challenges, rebuilding social capital is no longer merely a cultural ideal or luxury. It has become an urgent civic necessity. The future well-being of our cities, institutions, and even the sustainability of our planet depends on our ability to rekindle trust, nurture cooperation, and cultivate genuine care for one another.

The age of individualism need not become an age of loneliness and isolation. With creativity, commitment, and thoughtful design, we can build social systems and communities where people are not just consumers or isolated citizens, but neighbors, collaborators, and co-creators. By doing so, we restore social capital—not through nostalgia for the past, but through innovative approaches that reflect the realities and opportunities of our time.

Relevant Quotes:

|

To get PDF version, Please click on "Print PDF" button.

<div class="new-fform">

</div>

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/a31d139fd279a9fd9cd6f51254f642081ecad686204b74f0d27b162352f4d531.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/050a9e68992486a9b85772b7a96e831a60ebbdf007ce74a9a26c448c63a7c140.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/99993b5b8832441d78ee0ab389e0a6480e4046ab348b3c27c8e379421aebeaba.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/215ef339d37faa2e5637e29cd3c056a1d8236974a033c73bcfd49539e97fb3bc.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/b4d1de6143828c592d442c1acf4dda0ee8e35dd36291c3bfb5ed55c06e12060e.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/b0827f1b0ebd900ca48e2625b48c7117134410447ae5380d077da9488bfed828.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/8f04a444d6c346e09d64838558bdc11c026de3bd78f91ab58b74ace63ef48910.jpg