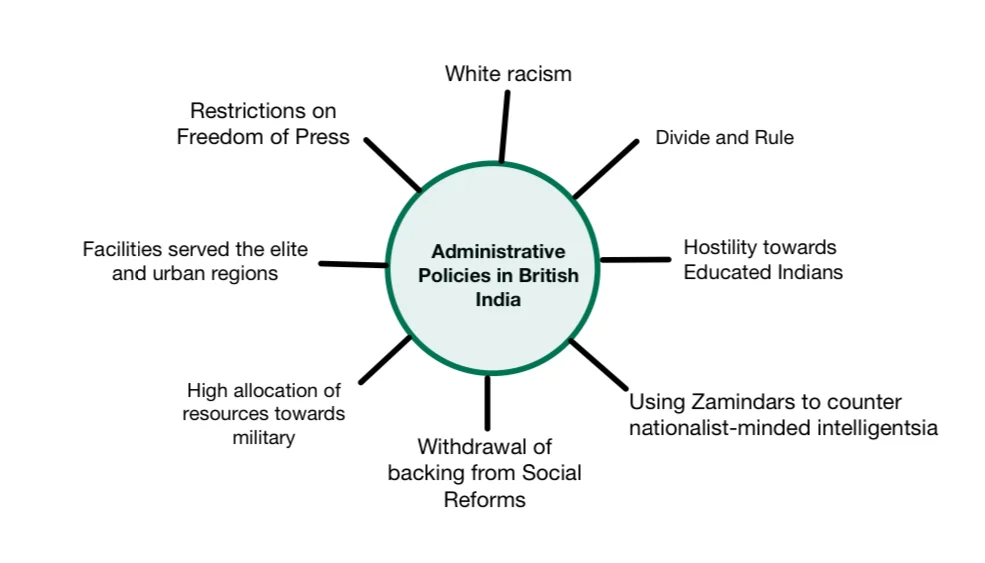

The British colonial administration in India shifted from progressive goals to conservative policies after 1857, aiming to maintain control and suppress nationalist movements. Through strategies like “divide and rule,” they fostered divisions among Indians and opposed the rising middle-class nationalist leaders. The administration’s repressive measures and disregard for social reforms contributed to India’s underdeveloped state.

Colonial Administrative Policies and their Impact on Indian Society

In contrast to their initial goals before 1857, which aimed to modernize India along progressive principles, the administration later embraced overtly conservative policies by asserting that Indians were unfit for self-rule and required the continued presence of the British in their lives.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

Divide and Rule

- Divide and Conquer Strategy: In a bid to prevent a unified mass challenge to their rule in India, the British colonial rulers opted for a strategy of “divide and conquer.”

- Exploiting Religious and Social Divides: They pitted princes against commoners, one region against another, province against province, and caste against caste, as well as fomented tensions between Hindus and Muslims.

- Strategic Use of Muslim Elite: After an immediate spell of repression against Muslims, following the 1857 revolt, the authorities decided, after 1870, to strategically employ the educated middle and upper classes among Muslims to counter the growing tide of nationalism.

- Manipulating Educational and Political Resources: They exploited conflicts arising from the limited resources available for education, administrative positions, and, later, political influence – which were inherent in the colonial system’s design – as a means to sow division along religious lines among educated Indians.

Hostile Attitude Towards Educated Indians

- Scrutiny of British Exploitation: The rising middle-class nationalist leaders were scrutinizing the exploitative nature of British colonial rule and were advocating for greater Indian involvement in the administration.

- Indian National Congress and the British Response: As the nationalist movement took its initial steps, marked by the founding of the Indian National Congress in 1885, the British perceived these actions as a direct challenge to their authority.

- Confrontational British Attitude: Consequently, they adopted a confrontational attitude towards this leadership.

- In fact, from that point onward, they resisted and opposed anyone who championed the cause of modern education.

| VIEWS |

| “All experience teaches us that where a dominant race rules another, despotism is the mildest form of government.”

–Charles Wood (the Secretary of State for India) |

| “Systems of nomination, representation and election were all means of enlisting Indians to work for imperial ends.”

–Anil Seal |

Attitude Towards the Zamindars

- British Alliances with Conservative Social Groups: In pursuit of regressive policies and to broaden their social support base, the British sought alliances with the most conservative social groups, such as the princes and zamindars.

- Elevating Zamindars and Landlords: The British intended to use these groups to counter the nationalist-minded intelligentsia.

- Consequently, the zamindars and landlords were elevated as the people’s ‘natural’ and ‘traditional’ leaders.

- Restoration of Confiscated Lands: Many of the confiscated lands of the Awadh taluqdars, taken before 1857, were returned to them.

- Protection of Zamindar Interests: The interests and privileges of the zamindars and landlords were safeguarded, often at the expense of the peasants.

- Zamindars’ Support for British Rule: In return, the zamindars and landlords viewed the British as protectors of their very existence and became staunch supporters of British rule.

Attitude Towards Social Reforms

- Withdrawal of Support for Social Reforms: Having chosen to align themselves with the conservative segments of Indian society, the British government withdrew their backing for social reforms, which they believed had provoked the opposition of orthodox factions.

- Fostering Caste and Communal Identities: Furthermore, by fostering caste and communal identities, the British inadvertently bolstered the influence of reactionary forces.

Underdeveloped Social Services

- Neglect of Social Services Due to Prioritization of Military and Administration: An excessively high allocation of resources towards the military, civil administration, and the expenses of wars left meager funds available for crucial social services such as education, healthcare, sanitation, and physical infrastructure.

- Long-lasting Impact on Social Infrastructure: This historical legacy continues to impact the country to this day.

- Moreover, the limited facilities that were established predominantly served the privileged elite and urban regions.

Labour Legislations

- Harsh Working Conditions in 19th-Century India: Similar to the early stages of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, the working conditions in factories and plantations in 19th-century India were extremely harsh.

- Working hours were excessively long, not only for men but also for women and children, and wages were minimal.

- Workers toiled in crowded, poorly ventilated, and dimly lit spaces with virtually no safety measures.

- The Role of Lancashire Capitalists in Labor Reforms: Ironically, the first call for regulations to improve working conditions in Indian factories came from the Lancashire textile capitalists.

- Fearing the rise of a competitive Indian textile industry based on cheap and unregulated labor, they demanded the establishment of a commission to investigate factory conditions.

- The first commission was appointed in 1875, after the first commission recommendation, the British government passed the Indian Factory Act 1881 and the Indian Factory Act 1891.

- N. M. Lokhande and the Rise of the Labor Movement: N. M. Lokhande was a pioneer in organizing the labor movement in British India.

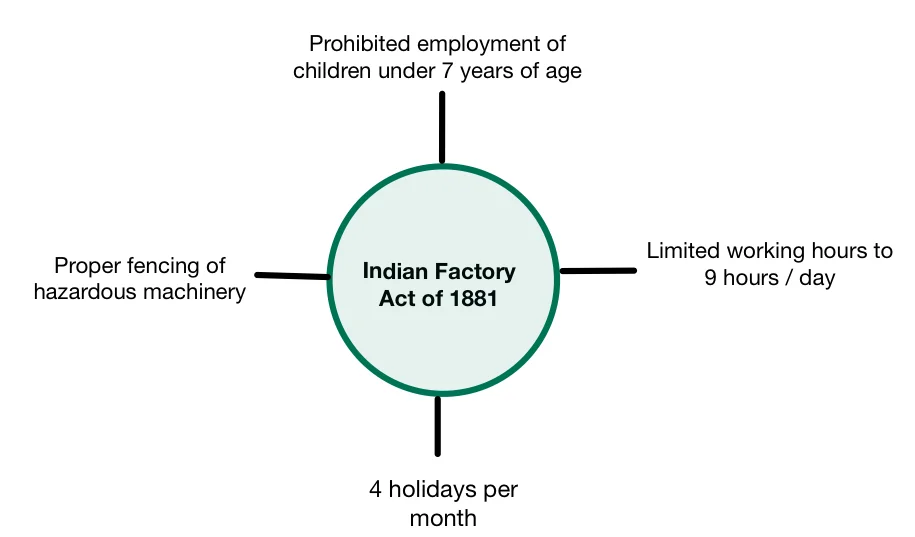

Indian Factory Act of 1881

- Key Provisions on Child Labor: The Indian Factory Act of 1881 primarily addressed the issue of child labor, setting significant provisions, including:

- Prohibition of the employment of children under 7 years of age.

- Limiting working hours to 9 hours per day for children.

- Granting children four holidays per month.

- Mandating the proper fencing of hazardous machinery to ensure safety.

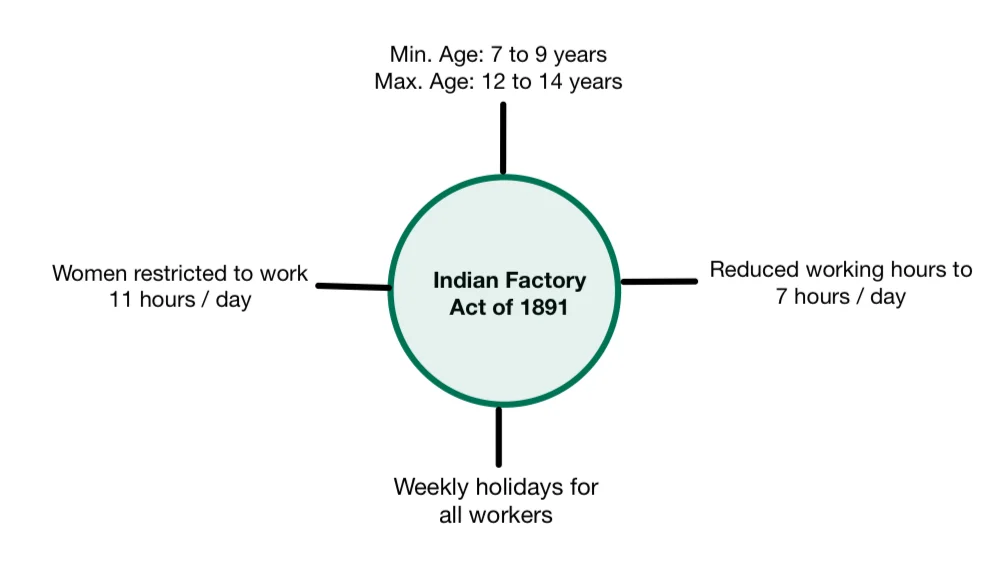

Indian Factory Act of 1891

- Extension of Child Labor Regulations: The Indian Factory Act of 1891

- The Act increased the minimum age for child labor from 7 to 9 years and the maximum age from 12 to 14 years.

- It reduced the maximum working hours for children to 7 hours per day.

- Women were restricted to 11 hours of daily work, with a one-and-a-half-hour break.

- A weekly holiday was introduced for all workers.

- Exploitation in British-Owned Plantations

- The labor laws did not apply to British-owned tea and coffee plantations, where workers were often exploited.

- Planters had the authority to arrest laborers for breaching contract terms, and breach of contract was considered a criminal offense.

- Limited Impact of Labor Laws

- Despite the introduction of labor laws in response to nationalist pressures in the 20th century, overall working conditions in India remained deplorable.

Narayan Meghaji Lokhande (1848–1897) Contribution for Labour Movement

- Father of the Trade Union Movement in India: Narayan Meghaji Lokhande (1848–1897) was the father of the trade union movement in India.

- He is remembered not only for ameliorating the working conditions of textile mill-hands in the 19th century but also for his courageous initiatives on caste and communal issues.

- Rights Secured for Mill Workers by Lokhande: Some of the rights mill workers got because of N M Lokhande were:

- Mill workers should get a weekly holiday on Sunday

- In the afternoon, workers should be entitled to half-hour recess.

- The mill should start working from 6:30 in the morning and close by sunset.

- The salaries of the workers should be given by the 15th of every month.

The Trade Disputes Act, 1929

- Purpose and Provisions: The Trade Disputes Act of 1929 was introduced as an experimental measure for five years to address trade disputes in India.

- It established Courts of Inquiry and Boards of Conciliation to investigate and resolve disputes between employers and workers.

- Restrictions on Strikes and Lockouts: The Act prohibited unauthorized strikes or lockouts in public utility services.

- Strikes or lockouts that were intended to cause significant hardship to the community or pressure the government into specific actions were also declared illegal.

- Focus on Legitimate Trade Disputes: The Act aimed to restrict strikes and lockouts to issues directly related to the trade or industry in question, disallowing actions with broader political or economic purposes.

- Amendments and Permanent Establishment: The Trade Disputes Act was amended in 1932 and was made permanent through the Trade Disputes (Extending) Act, 1934, formalizing its provisions and extending its impact on labor relations.

| VIEWS |

| “I am sorry to hear of the increasing friction between the Hindus and Mohammedans in the north-west and the Punjab. One hardly knows what to wish, for unity of ideas and action could be very dangerous politically; divergence of ideas and collision are administratively troublesome. Of the two, the latter is least risky, though it throws anxiety and responsibility upon those on the spot where the friction exists.”

–Hamilton (Secretary of State, 1897) |

| “The English were an imperial race, we were told, with God-given right to govern us and keep us in subjection; if we protested, we were reminded of the tiger qualities of an imperial race.”

–Jawaharlal Nehru |

Restrictions on Freedom of the Press

- Rise of Nationalist Press: Nationalists quickly embraced the new advancements in press technology to inform and shape public opinion, leveraging criticism and scrutiny to influence government policies and ignite national consciousness.

- Vernacular Press Act of 1878: In 1835, Metcalfe had lifted constraints placed on the Indian press.

- However, Lytton, apprehensive of the growing influence of the nationalist press on public sentiment, enforced restrictions on the Indian language press through the notorious Vernacular Press Act of 1878.

- Repeal of the Act: This act was eventually repealed in 1882 following public protests.

- For approximately two decades afterwards, the press enjoyed relative freedom.

- Repression During Swadeshi and Anti-Partition Movements: Nevertheless, the press found itself under renewed repression during the Swadeshi and anti-partition movements.

- Restrictions were reintroduced in 1908 and 1910, as the authorities sought to further curtail its influence.

White Racism

- Racial Hierarchy in Civil and Military Services: The colonial rulers upheld a strict racial hierarchy, systematically barring Indians from higher-ranking positions in both civil and military services.

- This deliberate exclusion maintained the dominance of the British over key sectors of governance and power.

- Racial Segregation in Public Spaces: Segregation was enforced in various public spaces such as railway compartments, parks, hotels, and clubs, where Indians were either given inferior facilities or completely excluded.

- This segregation was part of the broader colonial strategy to maintain control and assert racial superiority.

- Physical Violence and Racial Arrogance: The British exhibited racial arrogance through incidents of physical violence, often including beatings and even fatalities, which were dismissed as accidents.

- These actions were designed to reinforce their power and instill fear among the Indian population.

- Lord Elgin’s View on British Authority: As Lord Elgin expressed, “We could only govern by maintaining the fact that we were the dominant race. Although Indians in government services should be encouraged, there is a threshold at which we must retain control for ourselves if we are to maintain our authority.”

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

Conclusion

The British colonial policies not only hindered India’s progress but also exploited its resources and people for imperial gain.

- While some progress was made in industrial and administrative sectors, the overall impact was a legacy of inequality, division, and repression.

- These policies shaped the trajectory of India’s struggle for independence and its post-colonial challenges.

Sign up for the PWOnlyIAS Online Course by Physics Wallah and start your journey to IAS success today!

GS Foundation

GS Foundation Optional Course

Optional Course Combo Courses

Combo Courses Degree Program

Degree Program