Salt monopoly was a mixed package to appeal to a diverse cross section of political leaders and unite the Indians once again under one overarching political leadership. In Gandhi’s words, “There is no other article like salt, outside water, by taxing which the government can reach the starving millions, the sick, the maimed, and the utterly helpless… it is the most inhuman poll tax the ingenuity of man can devise.” Salt, according to Gandhi, swiftly connected the concept of swaraj with a tangible and widespread grievance of the rural poor, devoid of socially divisive implications like a no-rent campaign. Similar to khadi, salt provided a small yet psychologically significant income for the poor through self-help. Moreover, like khadi, it offered the urban population the opportunity for a symbolic identification with mass suffering.

Gandhi’s Eleven Demands

To advance the directives established by the Lahore Congress, Gandhi presented the government with eleven demands, accompanied by an ultimatum for acceptance or rejection by January 31, 1930. These demands encompassed various aspects:

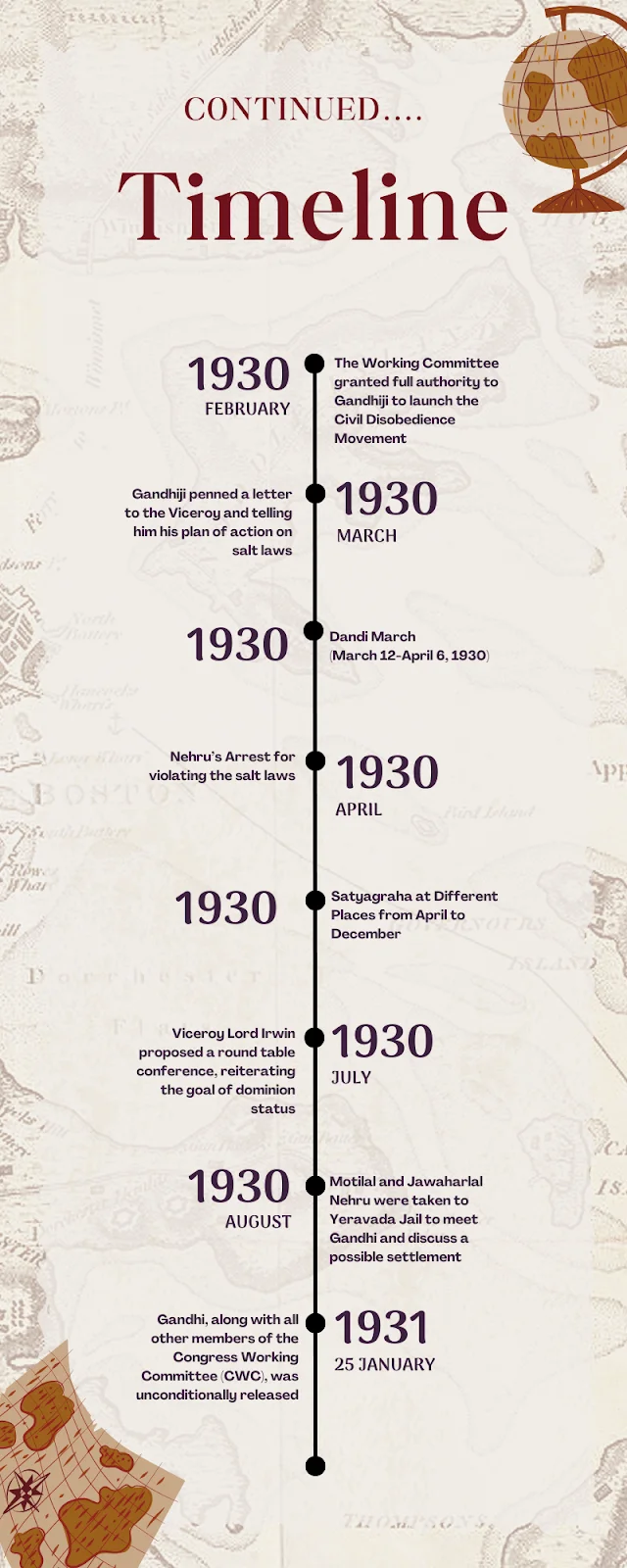

- Lahore Congress, 1929 Provided: The Lahore Congress of 1929 empowered the Working Committee to initiate a civil disobedience program, encompassing actions such as the non-payment of taxes.

- The Working Committee Authorized Gandhi Ji: Additionally, it urged all members of legislatures to resign from their seats. In February 1930, during a meeting at Sabarmati Ashram, the Working Committee granted full authority to Gandhiji to launch the Civil Disobedience Movement at a time and place of his choosing.

As the recognized expert in mass struggle, Gandhiji was actively seeking an effective formula for the movement.

His ultimatum to Lord Irwin on January 31, outlining minimum demands through 11 points, had gone unanswered. The only viable recourse now was civil disobedience. By the end of February, the formula began to crystallize, with Gandhiji focusing on salt as a symbolic and strategic element.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

Dandi March (March 12-April 6, 1930)

- On March 2, he penned a momentous letter to the Viceroy, eloquently detailing why he perceived British rule as a curse: “It has impoverished the dumb millions by a system of progressive exploitation… It has reduced us politically to serfdom. It has sapped the foundations of our culture… it has degraded us spiritually.”

| Gandhi outlined his plan of action, aligning with his convictions as a true Satyagrahi: “…on the 11th day of this month, I shall proceed with such co-workers of the Ashram as I can, to disregard the provisions of the salt laws. It is, I know, open to you to frustrate my design by arresting me. I hope that there will be tens of thousands ready, in a disciplined manner, to take up the work after me, and, in the act of disobeying the Salt Act, to lay themselves open to the penalties of a law that should never have disfigured the Statute-book.” |

- Journey Against the Salt Law: Under this plan, Gandhi, accompanied by seventy-eight members of Sabarmati Ashram, would march 240 miles from his headquarters in Ahmedabad through the villages of Gujarat. Upon reaching the coast at Dandi, the salt law would be violated by collecting salt from the beach.

Before the march commenced, thousands gathered at the ashram. Gandhi issued directives for future action:

- Initiate civil disobedience of the salt law wherever possible.

- Picket foreign liquor and cloth shops.

- Refuse to pay taxes if there is sufficient strength.

- Lawyers can abandon their practice.

- Boycott law courts by refraining from litigation.

- Government servants can resign from their posts.

- All these actions were contingent upon one condition—adherence to truth and non-violence as a means to attain swaraj. Local leaders were instructed to be followed after Gandhi’s arrest.

Efficacy of the Civil Disobedience Movement

Illustrating the efficacy of civil disobedience, Gandhi articulated, “If ten persons from each of the 700,000 villages in India come forward to manufacture salt and to disobey the Salt Act, what do you think this Government can do? Even the worst autocrat you can imagine would not dare to blow regiments of peaceful civil resisters out of a cannon’s mouth. If only you will bestir yourselves just a little, I assure you we should be able to tire this Government out in a very short time.”

- Gandhi’s Encouragement During Civil Disobedience: The historic march, marking the beginning of the Civil Disobedience Movement, commenced on March 12, Gandhi openly encouraged people to make salt from seawater in their homes and violate the salt law.

- Commencement of Civil Disobedience Movement: On April 6, 1930, by seizing a handful of salt, Gandhiji marked the commencement of the Civil Disobedience Movement—an unparalleled episode in the annals of the Indian national movement, characterized by widespread participation across the country.

The violation symbolized the Indian people’s determination not to live under British-made laws and, consequently, British rule. Newspapers extensively covered the march, its progression, and its impact on the people. In Gujarat, 300 village officials resigned in response to Gandhi’s appeal, and Congress workers focused on grassroots organizational tasks.

Spread of Salt Disobedience

Resonance of Salt Law Defiance: After Gandhi’s symbolic act at Dandi, the defiance of salt laws resonated throughout the country.

- Nehru’s arrest in April 1930, for violating the salt law, sparked massive demonstrations in Madras, Calcutta, and Karachi.

- Government’s Response: The swift proliferation of the movement compelled the Government to reveal the power concealed beneath its outwardly benevolent demeanor.

-

- Under mounting pressure from officials, Governors, and the military establishment, the Viceroy issued the order for Gandhiji’s arrest on May 4.

- Gandhiji’s declaration of leading a raid on the Dharasana Salt Works, continuing his defiance of the salt laws, undoubtedly pressured the Government. However, the timing of Gandhiji’s arrest was poorly chosen.

- It lacked the advantage of an early strike, which could have hindered Gandhiji’s careful buildup of momentum for the movement.

- Protests and Challenges for the Government: It failed to align with the Government’s policy of waiting it out. Instead, occurring at a pinnacle moment in the movement, it only served to intensify activity and create persistent challenges for the Government.

- Gandhi’s arrest triggered protests in Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta, and particularly in Sholapur, where the response was most intense.

- Cascading Impact of Gandhiji’s Arrest: After Gandhi’s symbolic salt march at Dandi in 1930, Nehru’s arrest for violating salt laws ignited massive demonstrations in Madras, Calcutta, and Karachi.

- The movement’s rapid spread forced the Viceroy to arrest Gandhi on May 4, following his announcement of leading a raid on the Dharasana Salt Works.

- Though Gandhi’s arrest pressured the government, its poorly-timed execution lacked the advantage of an early strike, intensifying rather than hindering the momentum of the movement.

- The arrest triggered protests across major cities, notably intense in Sholapur.

Following Gandhi’s arrest, the Congress Working Committee (CWC) approved several actions:

- Non-payment of revenue in Ryotwari areas.

- No-chowkidari-tax campaign in Zamindari areas.

- Violation of forest laws in the Central Provinces.

Satyagraha at Different Places

Tamil Nadu: In April 1930, C. Rajagopalachari orchestrated a march from Thiruchirapalli (Trichinapoly, as referred to by the British) to Vedaranniyam on the Tanjore (or Thanjavur) coast in Tamil Nadu to defy the salt law.

- Following this event, there was widespread picketing of foreign cloth shops, and the anti-liquor campaign gained substantial support in interior regions such as Coimbatore, Madura, Virdhanagar, etc.

- Despite Rajaji’s efforts to maintain non-violence, there were instances of violent eruptions from the masses, met with forceful repression by the police.

- In attempts to break the Choolai mills strike, a police force was deployed. Unemployed weavers attacked liquor shops and police pickets in Gudiyattam, while peasants, grappling with falling prices, rioted in Bodinayakanur in Madura.

- Malabar: In Malabar, K. Kelappan, a Nair Congress leader renowned for the Vaikom Satyagraha, organized salt marshes. P. Krishna Pillai, the future founder of the Kerala Communist movement, valiantly defended the national flag against a police lathi-charge on Calicut beach in November 1930.

- Andhra Region: In the Andhra region, district salt marches were coordinated in east and west Godavari, Krishna, and Guntur. Several sibirams (military-style camps) were established as headquarters for the Salt Satyagraha.

- Merchants contributed to Congress funds, and dominant caste Kamma and Raju cultivators resisted repressive measures. However, the region lacked the mass support witnessed during the non-cooperation movement (1921-22).

- Orissa: Gopalbandhu Chaudhuri led effective salt satyagraha in coastal regions, including Balasore, Cuttack, and Puri.

- Assam: Divisive issues hindered the movement’s success, but a student strike against the Cunningham Circular was notable in May 1930. Chandraprabha Saikiani incited aboriginal Kachari villages to break forest laws in December 1930.

- Bengal: In Bengal, the Congress was divided into two factions led by Subhas Bose and J.M. Sengupta, with involvement in the Calcutta Corporation election. This led to the alienation of many Calcutta Bhadralok leaders from the rural masses.

- Communal riots occurred in Dacca (now Dhaka) and Kishoreganj, with minimal participation from Muslims in the movements.

- Despite these challenges, Bengal witnessed the highest number of arrests and a significant amount of violence. Notably, Midnapur, Arambagh, and various rural areas experienced robust movements centered around salt satyagraha and chaukidari tax.

- Concurrently, during this period, Surya Sen’s Chittagong revolt group conducted a raid on two armouries and proclaimed the establishment of a provisional government.

- Bihar: In Bihar, Champaran and Saran were the initial districts to commence salt satyagraha. However, in landlocked Bihar, large-scale salt production was impractical, making it more of a symbolic gesture in most places.

- In Patna, Nakhas Pond became a chosen site for salt-making and breaking the salt law under Ambika Kant Sinha.

- Soon, a potent no-chaukidari tax agitation replaced salt satyagraha due to physical constraints in salt production.

- By November 1930, the sale of foreign cloth and liquor significantly declined, leading to administrative collapses in several parts, such as the Barhee region of Munger.

- Chhotanagpur: The tribal belt of Chhotanagpur (now in Jharkhand) witnessed instances of lower-class militancy.

- Bonga Majhi and Somra Majhi, influenced by Gandhism, led a movement in Hazaribagh that combined socio-religious reform along ‘Sanskritising’ lines.

- Followers were encouraged to give up meat and liquor while adopting khadi. However, it was noted that the Santhals engaged in illegal distillation of liquor on a large scale under the banner of Gandhi.

- Most big zamindars remained loyal to the government, while small landlords and better-off tenants participated in the movement, despite occasional dampening of enthusiasm due to increased lower-class militancy.

- Peshawar: In this region, Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan’s efforts in education and social reform had a political impact on the Pathans. Also known as Badshah Khan and Frontier Gandhi, Gaffar Khan initiated the first Pushto political monthly, Pukhtoon, and established the volunteer brigade ‘Khudai Khidmatgars,’ popularly known as the ‘Red Shirts.’

- Committed to the freedom struggle and non-violence, these volunteers played a crucial role in shaping the sociopolitical landscape.

- The arrest of Congress leaders in the NWFP on April 23, 1930, triggered widespread demonstrations in Peshawar. For over a week, the city virtually fell into the hands of the crowds until order was restored on May 4.

- Subsequently, martial law was imposed, leading to a reign of terror. Notably, a section of Garhwal Rifles soldiers refused to open fire on an unarmed crowd during this upsurge.

- Sholapur: The industrial town witnessed fierce protests, including strikes, the burning of government symbols, and the establishment of a virtual parallel government.

- Textile workers went on strike from May 7, and after Gandhi’s arrest, the CWC sanctioned various actions, including non-payment of revenue.

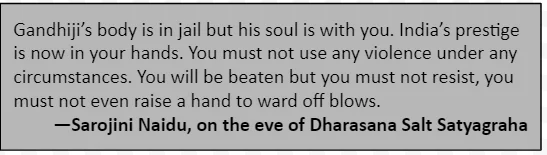

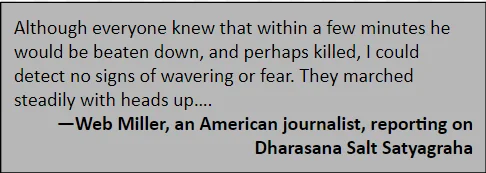

- Dharasana: On May 21, led by Sarojini Naidu, the first Indian woman President of the Congress, and Imam Saheb, a comrade of Gandhiji from the South African struggle, along with Gandhiji’s son, Manual, at the forefront, a group of 2000 individuals advanced toward the police cordon that had enclosed the Dharasana salt works, met with a brutal lathi-charge.

- Injured individuals were carried away by their companions on improvised stretchers, making room for another group to endure beatings, only to be similarly carried off; this procession continued, with each succeeding group sitting down to await police strikes rather than walking up to the cordon.

- By 11 a.m., with the temperature at 116 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, the toll stood at 320 injured and two dead.

- Webb Miller, the American journalist whose account of the Dharasana Satyagraha would disseminate the essence of Indian nationalism globally, eloquently portrayed the unwavering heroism of the Satyagrahis, emphasizing that nonviolent resistance was far from a passive endeavor, stating, ‘In eighteen years of my reporting in twenty countries, during which I have witnessed innumerable civil disturbances, riots, street fights, and rebellions, I have never witnessed such harrowing scenes as at Dharasana.’

This new form of salt satyagraha was adopted in Wadala (Bombay), Karnataka (Sanikatta Salt Works), Andhra, Midnapore, Balasore, Puri, and Cuttack.

- Gujarat: Impact was felt in Anand, Borsad, Nadiad, Bardoli, and Jambusar, with a determined no-tax movement and villagers evading repression by crossing borders.

- Maharashtra, Karnataka, and the Central Provinces: There was resistance against forest laws, including grazing and timber restrictions, as well as the public sale of forest produce acquired illegally.

- United Provinces: A no-revenue campaign was organized, urging zamindars to withhold payment of revenue to the government. Additionally, a no-rent campaign targeted tenants against loyalist zamindars.

- Since most zamindars were loyalists, the campaign essentially turned into a no-rent movement. The momentum increased in October 1930, particularly in Agra and Rai Bareilly.

- Manipur and Nagaland: At the age of thirteen, Rani Gaidinliu, a Naga spiritual leader, followed her cousin Haipou Jadonang, born in present-day Manipur, in raising the banner of revolt against foreign rule.

- Declaring that they were a free people and should not be ruled by white men, she urged people not to pay taxes or work for the British, aligning with the freedom struggle in the rest of India.

- Haipou Jadonang was captured and hanged on charges of treason in 1931, while Rani Gaidinliu managed to elude British authorities until her capture in October 1932.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

-

- She was subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment, and her release was ordered by the Interim Government of India in 1946 from Tura jail.

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

Conclusion

The Civil Disobedience Movement, marked by the Salt Satyagraha, was a pivotal chapter in India’s fight for independence. By challenging the unjust salt laws, Gandhi unified diverse sections of society against British rule. The movement’s widespread impact, from Dandi to various regions, demonstrated the power of nonviolent resistance. Despite facing severe repression, the movement galvanized national se

Sign up for the PWOnlyIAS Online Course by Physics Wallah and start your journey to IAS success today!

| Related Articles | |

| Civil Disobedience Movement | Lahore Session 1929 |

| Mahatma Gandhi | Rajagopalachari Formula |

GS Foundation

GS Foundation Optional Course

Optional Course Combo Courses

Combo Courses Degree Program

Degree Program