Historiography is the study of historical interpretation. It helps us appreciate the intellectual context of history, instead of just viewing it as a simple recollection of events. Historiography is important for a variety of reasons. For example, it explains why historical events have been interpreted differently over time. Similarly, historiography allows us to study history with a critical eye. It aids us in understanding what biases may have influenced the historical record.

Schools of Historiography

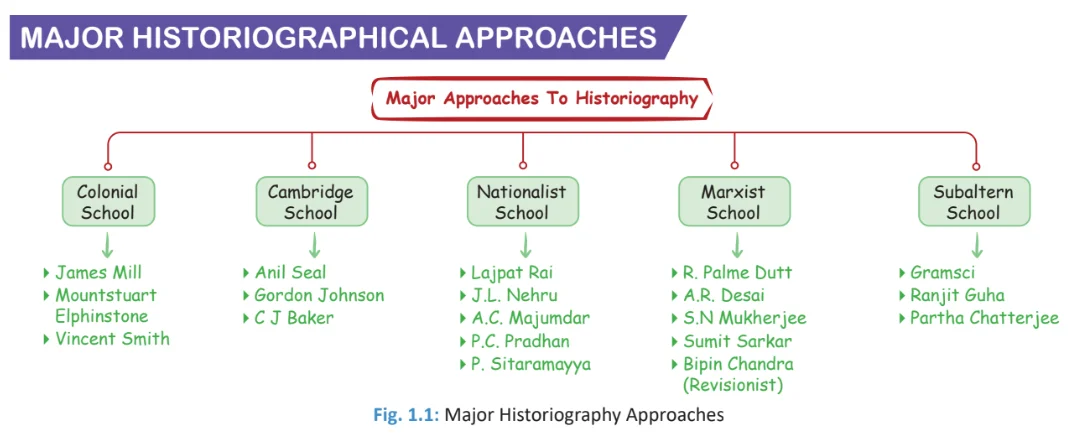

Main Schools: The modern history of India can be broadly divided into — the Colonial (or the Imperialist), Nationalist, Marxist, and Subaltern.

- Each approach has its distinct characteristics and ways of interpreting historical events.

- Other approaches: Communalist, Liberal and Neo-liberal, Cambridge and Feminist interpretations, which have also had a significant influence on how modern Indian history is written and understood.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

Colonial School (Shift issue Bansal sir resolve it)

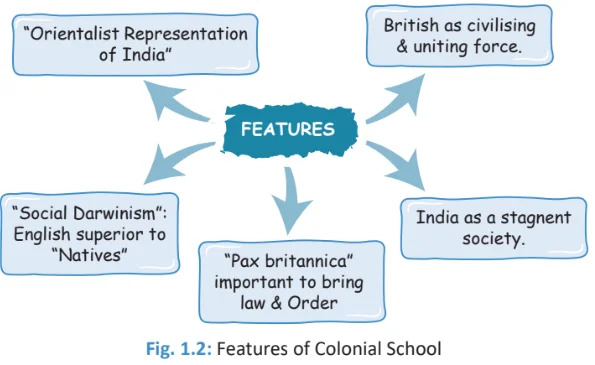

The “Colonial Approach” was a dominant perspective that held sway in India for much of the 19th century. This term is multifaceted in its meaning, encompassing two distinct dimensions.

- Historical Narratives and Ideological Influences: On one hand, it alludes to the historical narratives of colonial nations, while on the other, it relates to works influenced by the colonial ideology of control. In contemporary discussions, it is primarily in the latter context that historians delve into the realm of colonial historiography.

- Role of Documentation: The act of documenting colonial territories by colonial officials was intrinsically tied to their desire for dominance and the imperative of justifying colonial rule. Consequently, many of these historical accounts featured a critical portrayal of indigenous society and culture.

- Impact of the Colonial Approach and Western Values: Simultaneously, there was a palpable reverence for Western culture and values, accompanied by the exaltation of individuals who played pivotal roles in establishing colonial empires.

Key Details

- Major Proponents: James Mill (History of India), Mountstuart Elphinstone, Vincent Smith, Valentine Chirol (India Unrest).

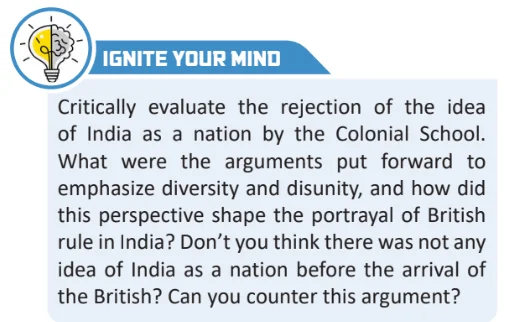

- Rejection of Idea of India as a Nation: The diversity and disunity of India were always emphasized by the colonialist thinkers as justification for the colonial rule which was considered to have united it.

-

- According to them, India was a conglomeration of different and often antagonistic religious, ethnic, linguistic, and regional groups that could never be welded into a nation.

- The strongest statement in this regard was provided by Valentine Chirol who, in his Indian Unrest (1910), asserted that India was a ‘mere geographical expression’, and even this geography was forged by the British.

- Benevolence of British Rule: This school viewed British rule in India as a benevolent and civilizing force that brought order, modernity, and progress to a supposedly backward and chaotic society.

- The above perspective was significantly articulated by Vincent Smith when he asserted that India would again become fragmented ‘if the hand of the benevolent despotism which now holds her in its iron grasp should be withdrawn’.

- British colonial administrators and historians tended to depict the movement as a series of sporadic and disconnected events, rather than a cohesive and concerted effort.

- Showing Merits in Colonial Rule: The Colonial School highlights the achievements of the British colonial administration, e.g., the introduction of modern education, railways, legal systems, and governance structures, as they had a positive influence on Indian society.

- Eurocentric Perspective: Indians are depicted as passive recipients of British policies and initiatives.

- It interpreted Indian history through a Eurocentric lens, evaluating developments in India about European benchmarks of progress and civilization.

- It interpreted Indian history through a Eurocentric lens, evaluating developments in India about European benchmarks of progress and civilization.

Nationalist School

The Nationalist School of Historiography sought to reinterpret Indian history with a focus on the achievements and contributions of Indian civilization, in contrast to the colonial perspectives that often depicted India as a passive recipient of British influence.

Key Details

- Proponents: During the colonial period, this school was represented by political activists such as Lajpat Rai, A.C. Mazumdar, R.G. Pradhan, Pattabhj Sitaramayya, Surendranath Banerjee, C.F. Andrews, and Girija Mukerji. More recently, B.R. Nanda, Bisheshwar Prasa, and Amles Tripathi have made distinguished contributions to this approach.

- Stirred Nationalistic Feelings: This school contributed to the growth of nationalist feelings to unify people in the face of religious, caste, or linguistic differences or class differentiation. It looks at the national movement as a movement of the Indian people.

- Exposed Colonialism and Credited Anti-colonial Movement: It exposed the exploitative character of colonialism and also gave credit to the fact that India was in the process of becoming a nation, and the national movement was a movement of the people

- It celebrated India’s historical achievements and also criticized the negative impact of colonial rule.

- It highlighted economic exploitation, cultural degradation, and social disintegration under British administration.

- It highlighted economic exploitation, cultural degradation, and social disintegration under British administration.

- Subhas Chandra Bose, in his Indian Struggle, argued that India possessed ‘a fundamental unity’ despite endless diversity. Jawaharlal Nehru also spoke about ‘unity in diversity’ and cultural unity amidst diversity, a bundle of contradictions held together by strong but invisible threads.

- It celebrated India’s historical achievements and also criticized the negative impact of colonial rule.

- Limitation: Their major weakness is that they tend to ignore or underplay the inner contradictions of Indian society both in terms of class and caste. They tend to ignore the fact that while the national movement represented the interests of the people or nation as a whole (that is, of all classes vis-a-vis colonialism) it only did so from a particular class perspective, and that, consequently, there was a constant struggle between different social, ideological perspectives for hegemony over the movement.

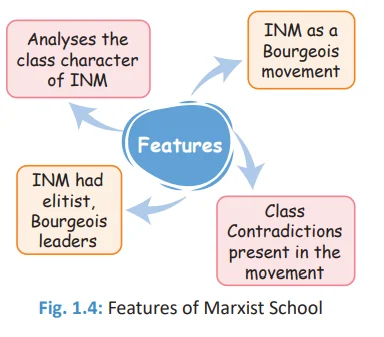

Marxist School

The Marxist historians have been critical of both the colonialist and nationalist views on Indian nationalism. They criticize the colonialist perspective for holding a discriminatory view of India and its people, while they criticize the nationalist commentators for seeking the roots of nationalism in the ancient past.

- They criticize both for not paying attention to economic factors and class differentiation in their analysis of the phenomenon of nationalism.

Key Details

- Proponents: The foundations of this school of historiography were laid by R. Palme Dutt and A.R. Desai. The later Marxist writings of S.N. Mukherjee, Sumit Sarkar, and Bipan Chandra have developed it further.

- R.P. Dutt formulated the most influential Marxist interpretation of Indian nationalism in his famous book India Today (1947).

- He stated that the revolt of 1857 “was in its essential character and dominant leadership the revolt of the old conservative and feudal forces and dethroned potentates”.

- R.P. Dutt formulated the most influential Marxist interpretation of Indian nationalism in his famous book India Today (1947).

- Bipin Chandra’s Revisionist Marxist School of Thought

- Bipan Chandra in his book ‘India’s Struggle for Independence’ (1988) has argued that the Indian nationalist movement was a popular movement of various classes, not exclusively controlled by the bourgeoisie.

Subaltern School

The Subaltern school derives its theoretical inputs from the writings of the Italian Marxist, Antonio Gramsci. According to it, the organized national movement, which ultimately led to the formation of the Indian nation-state was hollow nationalism of the elites, while real nationalism was that of the masses, whom it calls the ‘subaltern’.

Key Details:

- Proponents: Ranjit Guha, Partha Chatterjee, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Dipesh Chakrabarty.

- Interpretation: The Subaltern school of historiography dismisses all previous historical writing as elite historiography.

- For them, the basic contradiction in Indian society in the colonial epoch was between the elite, both Indian and foreign, on the one hand, and the subaltern groups, on the other, and not between Colonialism and the Indian people

- The subaltern perspective highlighted a “structural dichotomy” between elite politics and subaltern action, where the two lived in separate mental worlds.

- They believed that the Indian people were never united in a common anti-imperialist struggle and that there was no such entity as the Indian national movement.

| “The historiography of Indian nationalism has for a long time been dominated by elitism”. He further says that this “blinkered historiography”, cannot explain Indian nationalism, because it neglects “the contribution made by the people on their own, that is, independently of the elite to the making and development of this nationalism”. The opening statement of the first volume of the Subaltern Studies.

Edited by Ranajit Guha (Sekhar Bandyopadhyay). |

- Strands of National Movements: They assert that there were two distinct movements or streams, the real anti-imperialist stream of the subalterns and the bogus national movement of the elite.

- The elite stream was led by the ‘official’ leadership of the Indian National Congress.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

- Subaltern historiography first divides the movement into two and then accepts the neo-imperialist characterization of the elite stream.

- It too denies the legitimacy of the actual, historical anti-colonial struggle that the Indian people waged.

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

Conclusion

The study of historiography through various lenses, such as the Colonial, Nationalist, Marxist, and Subaltern schools offers a nuanced understanding of how history has been interpreted. Each school presents distinct perspectives, revealing the complexities and biases that shape historical narratives. Scholars like Partha Chatterjee argue for the integration of elite and subaltern politics, studying them in terms of their “mutually conditioned historicities.” The coexistence of elite and subaltern politics reveals the complex interactions that constituted the dominant themes in the period of Indian nationalism’s emergence and evolution.

Sign up for the PWOnlyIAS Online Course by Physics Wallah and start your journey to IAS success today!

| Related Articles | |

| Modern Indian History | Art & Culture |

| Indian National Movement: Rise of Nationalism and the Fight for Independence | The Rise of Nationalism in India: Key Events and Movements |

GS Foundation

GS Foundation Optional Course

Optional Course Combo Courses

Combo Courses Degree Program

Degree Program