The Rowlatt Act, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, and the imposition of martial law in Punjab shattered the generous wartime promises made by the British. The disillusionment deepened among Indian Muslims, who, realizing that promises of favorable treatment for Turkey after the War were mere manipulations, grew resentful. Between 1919 and 1922, the British faced opposition through two concurrent mass movements—the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation. While these movements originated from distinct issues, they embraced a shared strategy of nonviolent non-cooperation. Although the Khilafat issue was not directly tied to Indian politics, it served as the immediate backdrop for the movement and offered the additional advantage of fostering Hindu-Muslim unity in opposition to British rule.

Background

As the last year of the second decade of the twentieth century unfolded, India found itself steeped in discontent, and with valid reasons.

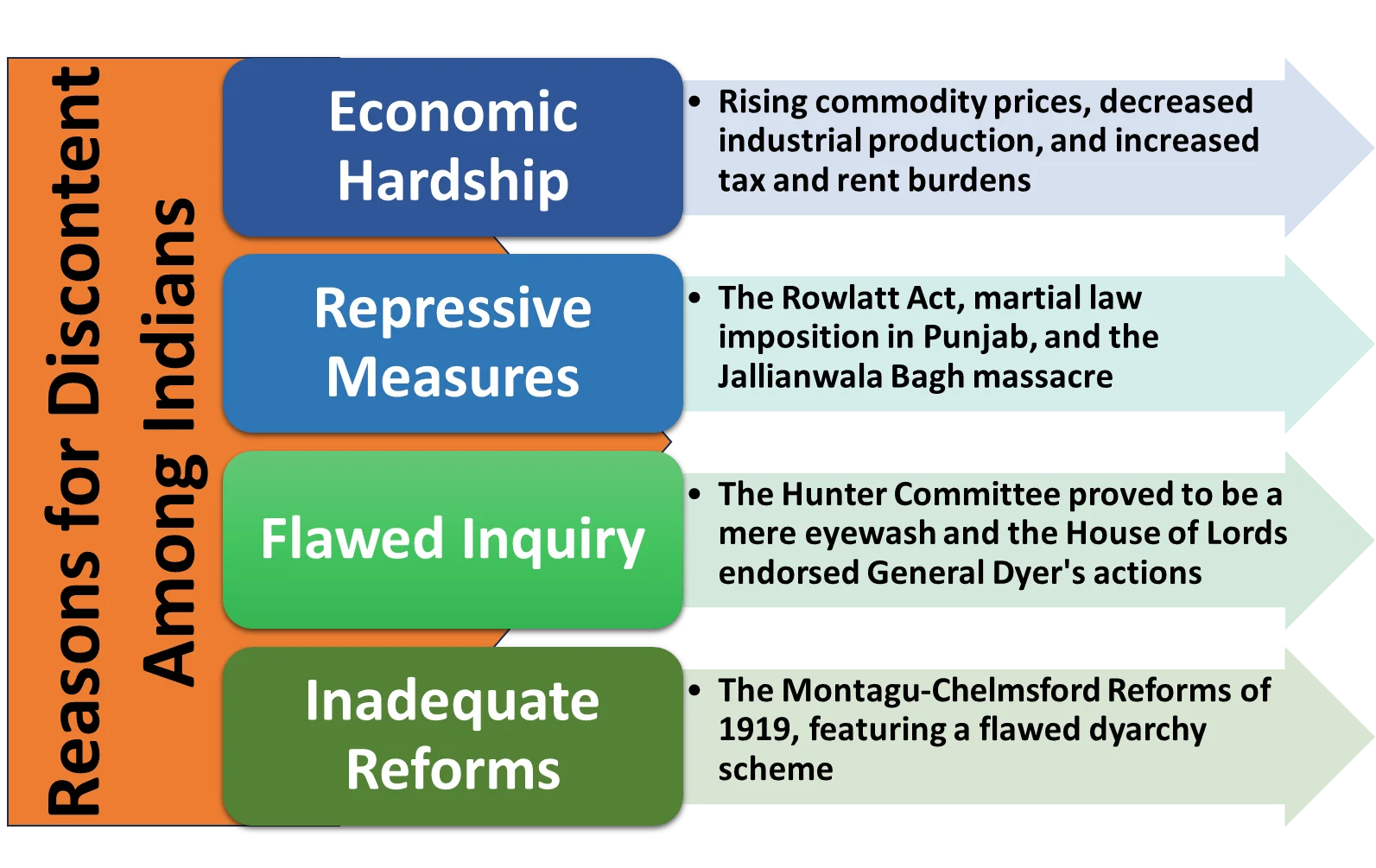

- Economic Conditions: Alarming economic conditions post-war, marked by rising commodity prices, decreased industrial production, and increased tax and rent burdens, inflicted hardship across society, fostering anti-British sentiments.

- Repressive Measures: The Rowlatt Act, martial law imposition in Punjab, and the Jallianwala Bagh massacre revealed the brutal and uncivilized nature of foreign rule, intensifying anti-British sentiments.

- Flawed Inquiry: The Hunter Committee, tasked with investigating Punjab atrocities, proved to be a mere eyewash. The House of Lords endorsed General Dyer’s actions, and public support, exemplified by The Morning Post’s fund collection of 30,000 pounds for him, underscored British solidarity.

- Inadequate Reforms: The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, introduced in late 1919, featuring a flawed dyarchy scheme, failed to meet Indian demands for self-government, deepening dissatisfaction and prompting a quest for more meaningful reforms.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

The Non-Cooperation Khilafat Movement

Early Indication: In February 1920, despite a joint Hindu-Muslim deputation seeking redress on the Khilafat issue, their mission to the Viceroy proved abortive.

- Gandhi, in the same month, declared that the Punjab wrongs and constitutional advancements were overshadowed by the Khilafat question.

- He hinted at leading a non-cooperation movement if the peace treaty failed to satisfy Indian Muslims.

- Treaty of Sevres: The Treaty of Sevres introduced in May 1920 exacerbated the situation, dismantling Turkey, which was signed in August 1920.

-

- In June 1920, an all-party conference in Allahabad endorsed a boycott of educational and legal institutions, urging Gandhi’s leadership.

- Official Start: The formal initiation of the movement occurred on August 1, 1920, following the lapse of the notice Gandhiji had provided to the Viceroy in his letter dated June 22.

- In that letter, he asserted the longstanding right of subjects to decline assistance to a ruler who misrules, a right recognized “from time immemorial.” Notably, B.G. Tilak passed away on August 1, 1920.

- Special Session, September 1922: In a special September 1920 session, the Congress endorsed a non-cooperation program addressing Punjab and Khilafat issues, establishing Swaraj.

The Non-Cooperation Movement of 1920-22 marked a significant shift in Indian politics, driven by the disillusionment Gandhi experienced in 1919. The enactment of the Rowlatt Acts, the tragic Jallianwalla Bagh incident orchestrated by General Dyer, and the Khilafat issues reshaped the political landscape. Gandhi, formerly a cooperator, initiated the Non-Cooperation campaign on August 1, 1920, in solidarity with the Khilafat movement.

Reorganization of Congress as an Institution

Congress Endorses Non-Cooperation: The Nagpur session in December 1920 saw Congress endorsing and formalizing the policy of Non-Violent Non-Cooperation against an unjust government.

- This session also witnessed the adoption of a new Congress Constitution, reiterating the goal of Swaraj within or outside the empire as necessary.

- Notably, the emphasis shifted from “constitutional means” to “all peaceful and legitimate methods,” symbolizing the onset of the Gandhian era.

- Establishment of a Modern Organizational Structure: It embraced a modern structure with local committees spanning villages, sub-divisions, districts, and provinces, culminating in the All India Congress Committee of 350 members at the apex; a Working Committee of 15 was to act as the chief executive.

-

- When Tilak initially proposed this idea in 1916, it faced resistance from the Moderate faction.

- Gandhiji was also aware that for a movement to be consistently guided, the Congress needed a cohesive organization functioning throughout the year.

- The Provincial Congress Committees were restructured along linguistic lines, facilitating communication with the public in the local language.

- The Congress aimed to establish organizational links at the village and neighbourhood levels through the creation of village and mohalla or ward committees.

- Affordable Membership: To make membership accessible to the economically disadvantaged, the annual fee was reduced to four annas.

- Mass Participation: This mass engagement not only broadened participation but also provided a consistent source of income for Congress.

- The organizational structure underwent streamlining and democratization.

- Hindi was to be prioritized in Congress communications wherever feasible.

Initiatives of the Khilafat Committee and the Congress

The Khilafat Committee and the Congress mutually aimed at Non-Cooperation with three objectives:

- Addressing the Khilafat issue,

- Rectifying Punjab’s wrongs, and

- Achieving Swaraj.

- The Khilafat Committee, in a June 6, 1920 meeting, delineated four stages of non-cooperation, including resignation from

- Honorary titles,

- Civil services,

- Police, and army, and

- Non-payment of taxes.

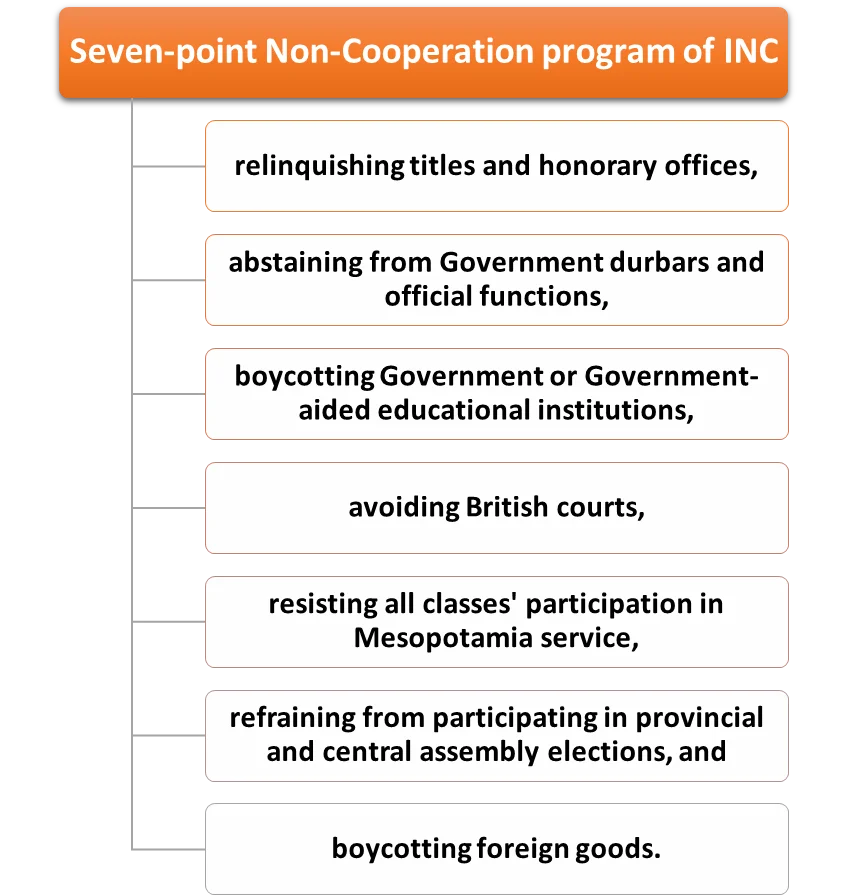

- Seven-Point Non-Cooperation Strategy: The Indian National Congress in September 1920 outlined a seven-point Non-Cooperation program involving surrendering titles, boycotting official events and institutions, rejecting foreign goods and popularizing the use of khadi, and boycotting law courts.

- Promotion of National Education: People were encouraged to establish national educational institutions and resolve disputes through mutual arbitration.

- Gandhi’s nationwide tours aimed to galvanize public enthusiasm, leading to approximately 30,000 arrests in 1921.

- Divide Over Boycott of Council Elections: There were differing opinions on this matter, with leaders, like C.R. Das was initially reluctant to endorse a boycott of councils. However, they eventually acquiesced to Congress’s discipline.

- These leaders chose to boycott the elections conducted in November 1920, a sentiment echoed by the majority of voters who also abstained from participating.

Response from Various Groups to the Congress Programme

The Congress’ adoption of the non-cooperation movement, initially proposed by the Khilafat Committee, infused it with newfound vigor, leading to an unprecedented popular upsurge in the years 1921 and 1922.

- Revolutionary Groups: Various revolutionary terrorist groups, particularly those from Bengal, expressed their support for the Congress program.

- Constitutional Struggle: During this period, leaders such as Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Annie Besant, G.S. Kharpade, and B.C. Pal distanced themselves from Congress, advocating for a constitutional and lawful struggle.

- Formation of the Indian National Liberal Federation: Concurrently, figures like Surendranath Banerjea established the Indian National Liberal Federation, playing a minor role in national politics thereafter.

Spread of the Movement

Targeting Schools and Colleges: Gandhi, accompanied by the Ali brothers, embarked on a nationwide tour. Thousands of students abandoned government schools, joining approximately 800 national schools and colleges that emerged during this period.

- Led by Acharya Narendra Dev, C.R. Das, Lala Lajpat Rai, Zakir Hussain, and Subhash Bose (who became the principal of the National College in Calcutta), these educational institutions included Jamia Millia in Aligarh, Kashi Vidyapeeth, Gujarat Vidyapeeth, and Bihar Vidyapeeth.

- Leading by Example: Numerous lawyers, including Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru, C.R. Das, C. Rajagopalachari, Saifuddin Kitchlew, Vallabhbhai Patel, Asaf Ali, T. Prakasam, and Rajendra Prasad, gave up their practice.

- Public burnings of foreign cloth significantly reduced imports, and picketing targeted shops selling foreign liquor and toddy.

- The Tilak Swaraj Fund exceeded its target, collecting one crore rupees.

- Congress Volunteer Corps: The Congress Volunteer Corps functioned as a parallel police force. In July 1921, the Ali brothers urged Muslims to resign from the Army for religious reasons, resulting in their arrest in September.

- Gandhi echoed this call, encouraging local Congress committees to pass similar resolutions.

- The emergence of the Congress Volunteer Corps posed a significant challenge to the government, with its disciplined members acting as a formidable parallel police force.

- Spread in Various Provinces: The Prince of Wales’s visit to India in November 1921 triggered strikes and demonstrations.

- Escalation of Civil Disobedience: The authorization given to Provincial Congress Committees (PCCs) to approve mass civil disobedience further intensified the movement.

- Cultivators’ Strikes and No-Tax Movements: Midnapur experienced a cultivators’ strike against a White Zamindari company led by a Calcutta medical student. In regions like Midnapur in Bengal Chirala-Pirala and Pedanandipadu taluqa in Guntur district of Andhra, no-tax movements gained momentum in defiance of forest laws.

- Peasant and Tribal Uprisings: While movements for better conditions of life emerged among peasants and tribals in some Rajasthan states, in Punjab, the Akali Movement, aiming for control of gurudwaras from corrupt mahants (priests), aligned with the broader Non-Cooperation Movement, maintaining strict non-violence despite significant repression.

- Labor Strikes and Repression in Assam: Assam witnessed strikes by laborers on tea plantations, with further strikes on the steamer service and Assam-Bengal Railway when workers were fired upon. J.M. Sengupta played a pivotal role in these events.

- Indirect Impacts of the Movements: Beyond direct impacts, the Non-Cooperation Movement had indirect consequences. In the Avadh area of U.P., where kisan sabhas and a Kisan movement had been gaining momentum since 1918, Non-Cooperation propaganda, spearheaded by figures like Jawaharlal Nehru, contributed to the existing fervor.

- Intersection of Non-Cooperation and Agrarian Movements: This resulted in blurred lines between Non-Cooperation and Kisan meetings.

- In Malabar, Kerala, Non-Cooperation and Khilafat propaganda played a role in arousing Muslim tenants against landlords, though occasionally taking on communal undertones.

- Intersection of Non-Cooperation and Agrarian Movements: This resulted in blurred lines between Non-Cooperation and Kisan meetings.

The Non-Cooperation Movement’s spirit of unrest and defiance contributed to the rise of various local movements throughout the country, often deviating from the Non-Cooperation Movement’s program or even the policy of non-violence.

People’s Response

Participation in the movement spanned a broad spectrum of society, albeit to varying degrees.

- Middle Class: Initially, the movement was led by the middle class, but reservations about Gandhi’s program emerged later, particularly in elite political centers like Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras.

- The call for resignation from government service and surrendering titles saw limited response.

- Emerging political figures like Rajendra Prasad in Bihar and Vallabhbhai Patel in Gujarat found non-cooperation a viable alternative to terrorism.

- Business Class: While the economic boycott found support among Indian businesses benefiting from the emphasis on swadeshi, some large businesses remained skeptical, fearing potential labor unrest.

- Peasants: Peasants played a massive role, in breaking Congress’s stance against class war.

- In Bihar, the confrontation between ‘lower and upper castes’ merged with the Non-Cooperation Movement, with peasants turning against landlords and traders.

- Students: Students actively volunteered, leaving government schools for newly opened national institutions like Kashi Vidyapeeth, Gujarat Vidyapeeth, and Jamia Millia Islamia.

- Women: Women abandoned purdah, contributing ornaments to the Tilak Fund, and actively participating in picketing foreign cloth and liquor shops.

- Hindu-Muslim Unity: Muslim participation and communal unity, despite events like the Moplah Uprisings, were significant achievements.

- In many places, two-thirds of those arrested were Muslims, a remarkable and unprecedented level of participation.

- Gandhi addressed Muslim masses from mosques, even addressing meetings of Muslim women without being blindfolded.

Government Response

Efforts to reconcile between Gandhi and Reading, the viceroy, collapsed in May 1921 when the government sought Gandhi’s intervention to remove portions from speeches by the Ali brothers that hinted at violence. Recognizing the government’s attempt to create division, Gandhi resisted falling into the trap. In December, the government cracked down on protestors, declaring volunteer corps illegal, imposing a ban on public meetings, gagging the press, and arresting most leaders, excluding Gandhi.

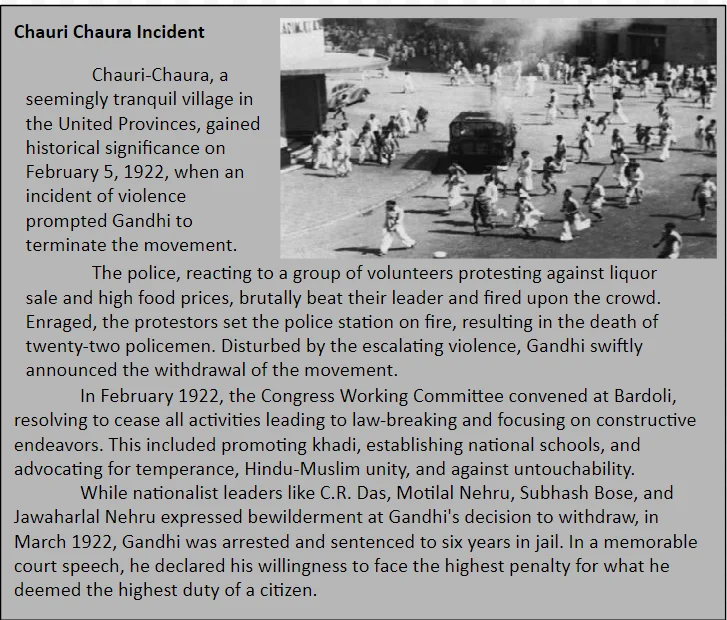

The Last Phase of the Movement

As pressure mounted from the Congress rank and file, Gandhi faced increasing calls to initiate the civil disobedience program. The Ahmedabad session in 1921, presided over by C.R. Das in jail (with Hakim Ajmal Khan as the acting president), designated Gandhi as the sole authority on the issue. On February 1, 1922, from Bardoli (Gujarat), Gandhi threatened civil disobedience unless political prisoners were released, and press controls were lifted. However, the movement was abruptly halted shortly after its initiation.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

Conclusion

The Non-Cooperation and Khilafat Movements brought about significant changes in Indian political dynamics from 1920 to 1922. Fueled by general disappointment with British authority and the manipulation of religious and nationalist feelings, these movements brought together various Indian groups in a shared effort of peaceful protest. Even though they were later halted, they promoted increased political awareness and restructured the Indian National Congress, establishing the groundwork for upcoming independence movements.

Sign up for the PWOnlyIAS Online Course by Physics Wallah and start your journey to IAS success today!

GS Foundation

GS Foundation Optional Course

Optional Course Combo Courses

Combo Courses Degree Program

Degree Program