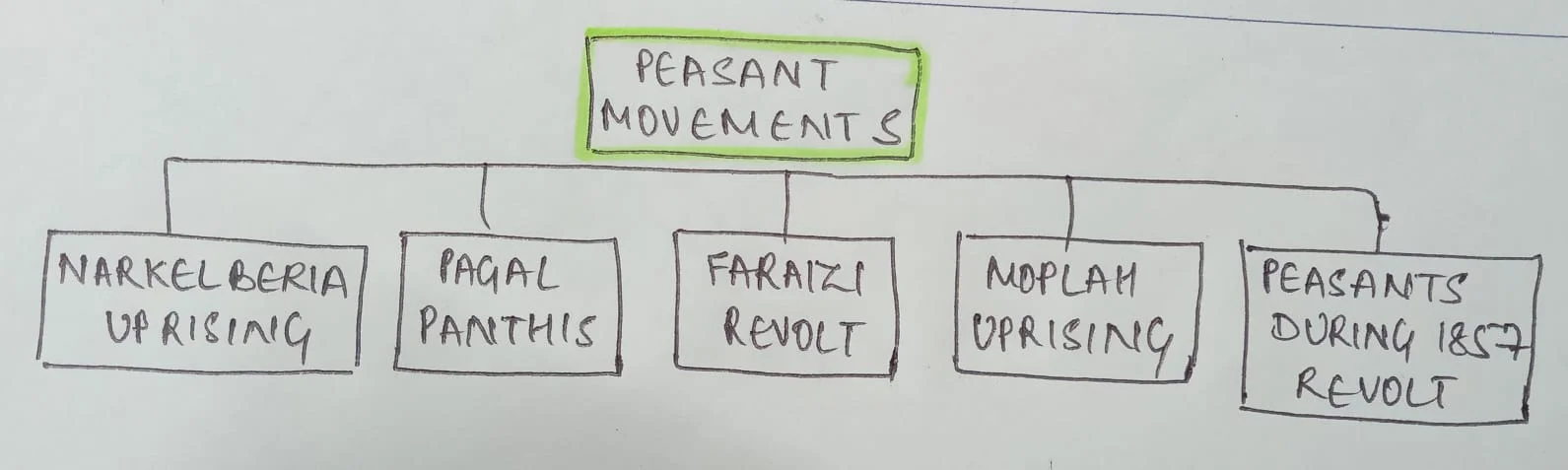

Peasant uprisings in India before the outbreak of the Revolt of 1857 were protests against evictions, rent hikes, and the exploitative practices of moneylenders. The main objective was to secure occupancy rights for peasants, among other demands. These movements were primarily driven by the peasants themselves, although they were often led by local leaders.

Some important peasant movements are discussed below:

Narkelberia Uprising:

Leader: It was led by Mir Nithar Ali (1782-1831) or Titu Mir, and was a significant movement in West Bengal.

- Issue and Course: Titu Mir inspired Muslim tenants to rebel against both Hindu landlords, who levied a beard tax on the Faraizis, and British indigo planters.

- Initially an armed peasant uprising against the British, the movement eventually took on a religious dimension.

- It later merged into the broader Wahabi movement.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

Pagal Panthis Revolt

- Leader and Location: Karam Shah established the Pagal Panthi, a semi-religious group that primarily consisted of the Hajong and Garo tribes of the Mymensingh district (previously in Bengal).

- Course: However, the zamindars’ oppression was met with resistance by the tribal peasants, who united under Tipu, the son of Karam Shah.

- Between 1825 and 1835, the Pagal Panthis attacked zamindars’ homes and refused to pay rent above a predetermined amount.

- British Response: To protect the peasants, the government put in place an equitable system, but the movement was brutally put down.

Faraizi Revolt

- Leader and Location: The Faraizi Revolt was led by the followers of a Muslim sect founded by Haji Shariat-Allah from Faridpur in Eastern Bengal.

- Main Idea: The Faraizis advocated for significant religious, social, and political reforms. Under the leadership of Shariat-Allah son of Dadu Mian (1819-60), the sect aimed to remove the English presence from Bengal.

- Additionally, they supported the rights of tenants against the zamindars.

- This revolt persisted from 1838 to 1857, and many of the Faraizis eventually joined the ranks of the Wahabi movement.

Moplah Uprisings

Reason and Location: Widespread unrest among the Moplahs of Malabar was sparked by an increase in revenue demands, a reduction of field sizes, and the oppressive behaviour of officials.

- Course: Between 1836 and 1854, twenty-two rebellions took place, but none of them achieved success.

- Reorganization of the Moplahs: Later, during the Non-cooperation Movement, the Moplahs were organized by the Congress and Khilafat supporters for a second uprising.

- Sectarian Tensions: However, Hindu-Muslim differences caused a rift between the Congress and the Moplahs. By 1921, the Moplahs had been suppressed.

Peasants’ Role in the 1857 Revolt

| Peasant Movements | Year | Area | Leaders |

| Narkelberia Uprising | 1831 | 24 Parganas, in Bengal | Titu mir |

| Pagal Panthis | 1825-35 | Mymensingh district, in Bengal | Karam Shah and his son, Tipu |

| Faraizi Revolt | 1838-57 | Faridpur, in Eastern Bengal | Shariat-Allah |

| Moplah Uprising | 1836- 1854 | Malabar, in Kerala | Variyamkunnath Kunjahammed Haji |

- Peasant participation in the 1857 rebellion was particularly active in areas like western Uttar Pradesh.

- Post-Revolt Conditions: They often allied with local feudal leaders to resist foreign rule. However, after the revolt, the condition of peasants worsened.

- British Policies Favoring Landed Classes: The British government prioritized gaining the support of the landed classes while overlooking the interests of the peasants. Occupancy rights for peasants were adversely affected.

- Land Reallocation: For instance, in Avadh, land was returned to the taluqdars with added revenue and other powers, while the peasants couldn’t benefit from the provisions of the 1859 Bengal Rent Act.

- Additionally, in some regions, peasants were levied with an additional cess as a punitive measure for their participation in the 1857 revolt.

- Land Reallocation: For instance, in Avadh, land was returned to the taluqdars with added revenue and other powers, while the peasants couldn’t benefit from the provisions of the 1859 Bengal Rent Act.

Ramosi Risings

Reason: The Ramosis, a hill tribe residing in the Western Ghats, did not accept British rule and its associated administrative practices.

- They were discontented with the policy of annexation, especially after the Maratha territories were taken over by the British.

- As a consequence, the Ramosis, who were previously employed by the Maratha administration, lost their livelihoods.

- Leader and Course: In 1822, they rebelled under Chittur Singh, engaging in plunder around Satara.

-

- Subsequent eruptions occurred in 1825-26 led by Umaji Naik of Poona and his supporter Bapu Trimbakji Sawant, continuing until 1829.

- The unrest resurfaced in 1839, triggered by the deposition and banishment of Raja Pratap Singh of Satara, and there were further disturbances in 1840-41.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

- British Response: Ultimately, a more powerful British force intervened to restore order in the region. Generally, the British pursued a conciliatory approach towards the Ramosis, even enlisting some of them into the hill police.

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

Conclusion

The peasant uprisings preceding the 1857 Revolt were crucial in highlighting the deep-seated discontent with British colonial policies and exploitation. From the Narkelberia and Pagal Panthis revolts to the Faraizi and Moplah uprisings, these movements underscored the peasants’ struggle for justice and autonomy. Despite their vital role in the 1857 Revolt, the post-revolt period saw worsening conditions for peasants, with British policies favoring landowners and further oppressing tenant farmers.

Sign up for the PWOnlyIAS Online Course by Physics Wallah and start your journey to IAS success today!

| Related Articles | |

| The Revolt of 1857: India’s First War of Independence | British Policy in India |

| Non-Cooperation Movement & Khilafat Movement | Peasant Struggles In Colonial India (1857–1947) |

GS Foundation

GS Foundation Optional Course

Optional Course Combo Courses

Combo Courses Degree Program

Degree Program