The early 19th century marked the beginning of the nationalist movement in India, during which press freedom became a central issue. Prominent figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and journalists across the country used newspapers to critique colonial policies and foster public opinion. Despite facing stringent government restrictions, they relied on the press as a vital tool for spreading nationalist ideologies.

The Struggle for Press Freedom in Colonial India

Early Advocates of Press Freedom

- Advocacy for Press Freedom by Raja Rammohan Roy (1824): From the early 19th century onward, the defense of civil liberties, including the freedom of the press, was a top priority for Indian nationalists.

- As early as 1824, Raja Rammohan Roy raised his voice in opposition to a resolution that aimed to restrict press freedom.

- The Role of the Press in Early Nationalist Movements (1870-1918): During the initial phase of the nationalist movement, roughly spanning from 1870 to 1918, the focus was primarily on political propaganda, education, the development and dissemination of nationalist ideologies, and the mobilization and consolidation of public opinion.

- The Press and the Indian National Congress: This period prioritized these activities over mass agitation or active mobilization of the masses through public gatherings.

- To achieve these goals, the press emerged as a critical tool in the hands of the nationalists.

- The Indian National Congress, in its early days, relied heavily on the press to disseminate its resolutions and proceedings.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

Role of Newspapers in Nationalist Mobilization

Numerous newspapers were established during this period, often led by fearless and distinguished journalists. These publications are:

| Newspaper | Founder |

| Bengal Gazette (1780) Calcutta | James Augustus Hickey (1st newspaper in India) |

| Sambad Kaumudi in Bengali (1821) Mirat-ul-Akhbar in Persian (1822) | Raja Ram Mohan Roy |

| Bombay Times (from 1861 Times of India), 1838, Bombay | Thomas Bennett |

| Rast Goftar (1851) | Dadabhai Naoroji (Gujarati fortnightly) |

| Hindu Patriot (1853) (Calcutta) | Girish Chandra Ghosh |

| Indian Mirror (1862) (Calcutta) | Devendranath Tagore (first Indian daily newspaper in English) |

| Som Prakash, 1859 | Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar |

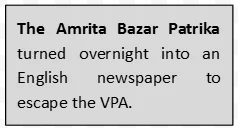

| Bengalee (this along with Amrita Bazar Patrika were the 1st vernacular papers), 1862, Calcutta | Girish Chandra Ghosh (taken over by S N Banerjea) |

| Indian Mirror (Manmohan Ghose was the first Editor) | N.N. Sen |

| Amrita Bazar Patrika (1868), Jessore district, undivided Bengal | Sisir Kumar Ghosh & Motilal Ghosh |

| The Hindu (1878) (Madras) | G.S. Aiyar, Viraraghavachari & Subba Rao Pandit |

| Kesari and Maharatta, (1881) (Bombay) | Tilak, Chiplunkar & Agarkar |

| Swadesamitran, Madras | G.S. Aiyar |

| Paridasak,1886 | Bipin Chandra Pal (Publisher) |

| Yugantar, 1906, Bengal | Barindra Kumar Ghosh and Bhupendra Dutta |

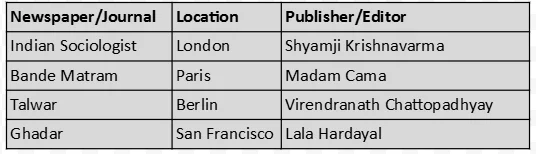

| Bande Mataram (Paris) | Madam Bhikaji Cama |

| Bombay Chronicle (1913) | Pherozshah Mehta Editor: B.G Horniman |

| The Hindustan Times, 1920, Delhi | K M Panikkar |

| Mook Nayak (1920) Bahishkrit Bharat (1927) (Marathi) | B R Ambedkar |

| Bandi Jivan, Bengal | Sachin Sanyal |

| National Herald, 1938 | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Young India, Harijan | Mahatma Gandhi |

- The Purpose and Impact of Nationalist Newspapers: These newspapers were not established as for-profit business ventures but were viewed as serving the nation and the public.

- Expansion Beyond Urban Areas: They had a significant reach and played a role in stimulating a library movement.

- Their impact extended beyond urban areas, reaching remote villages, where each news item and editorial would be thoroughly read and discussed in “local libraries” that formed around a single newspaper.

- The Newspapers as Institutions of Political Opposition: These libraries served the dual purpose of political education and political participation.

- The newspapers critically examined government acts and policies and functioned as institutions of opposition to the government.

Government Responses and Legal Challenges

- Government Response: In response, the government enacted stringent laws, such as Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code, which stipulated severe penalties for anyone attempting to foment disaffection against the British Government in India.

- Clever Strategies by Nationalist Journalists: Journalists circumvented legal obstacles through subtle tactics, such as starting articles with expressions of loyalty to the government.

- They also quoted critical writings from socialist or Irish nationalist newspapers in England, creating a balance of indirect critique and cautious dissent.

- The Vernacular Press Act of 1878: From its inception, the national movement advocated for the freedom of the press.

-

- Indian newspapers became highly critical of Lord Lytton’s administration, particularly regarding its treatment of the victims of the famine of 1876-77.

- In response, the government enacted the Vernacular Press Act of 1878.

Vernacular Press Act, 1878

Background to the Vernacular Press Act (VPA) of 1878

- Legacy of the 1857 Rebellion: The aftermath of the Rebellion of 1857 left a bitter legacy of racial animosity between the British rulers and the Indian populace.

- As a result, the European press in India consistently supported the government in all political disputes after 1858.

- Rise of the Vernacular Press: The vernacular press grew significantly after 1857, becoming increasingly critical of the government’s actions, especially Lord Lytton’s imperial policies.

- The 1876-77 Famine and Extravagance: The terrible famine of 1876-71, which claimed the lives of over six million people, and the extravagant expenses associated with the Imperial Durbar in Delhi in January 1877 further fueled public discontent.

- Lord Lytton’s Response: Lord Lytton, on his part, viewed the emerging intellectual class in India as a dangerous legacy from Macaulay and Metcalfe and sought to suppress their views.

- Introduction of the Vernacular Press Act: In response to the critical stance of the vernacular press, the British colonial government introduced the Vernacular Press Act (VPA) with the aim of exerting greater control over the vernacular press and punishing seditious writings effectively.

The Provisions of the Act included

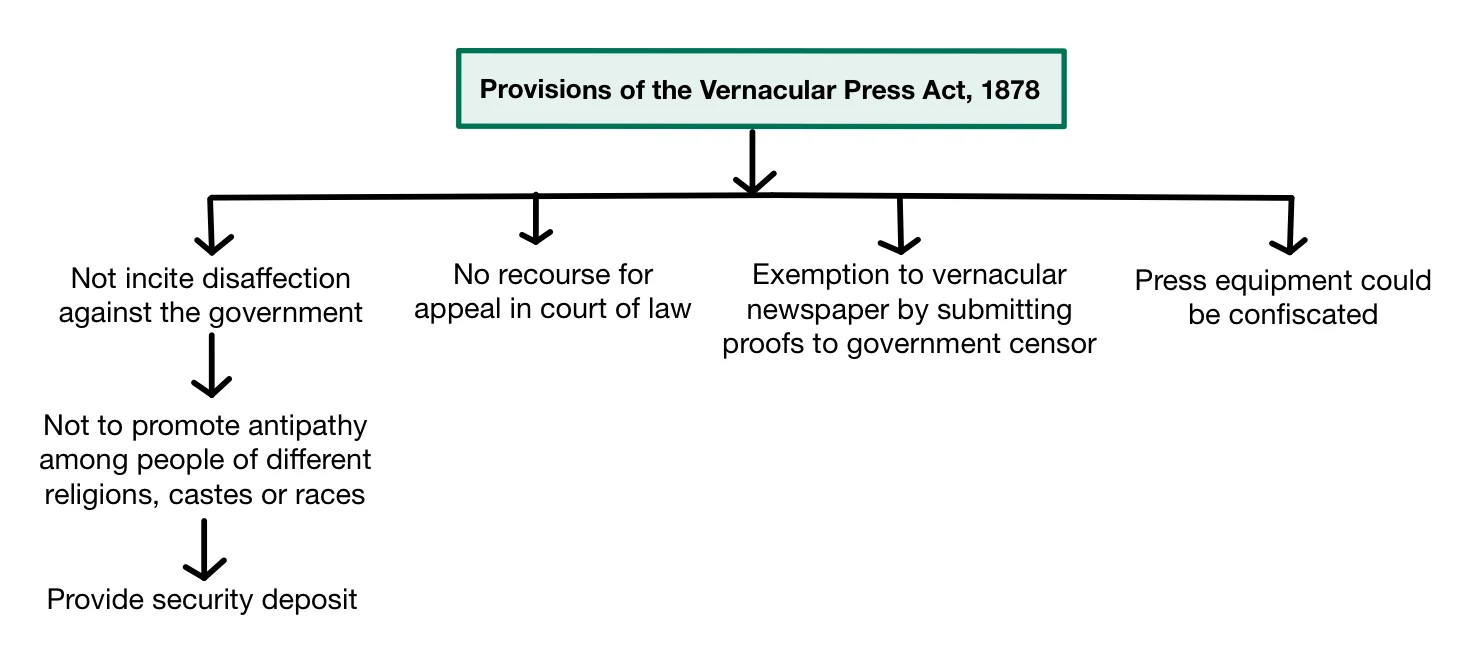

- Bond Requirement: A District Magistrate, with prior permission from the Local Government, to compel the printer and publisher of any vernacular newspaper to enter into a bond, undertaking not to publish material likely to incite disaffection against the government or create antipathy among individuals of different races, castes, and religions among the subjects of Her Majesty.

- Security Deposit: The magistrate could also require the publisher to provide a security deposit, which could be forfeited if the newspaper violated the regulation.

- In case of repeated offenses, the press equipment could be seized.

- No Appeal: It vested final authority in the district magistrate, with no recourse for appeal in a court of law.

- Exemption Clause: It allowed a vernacular newspaper to seek exemption from the Act by submitting proofs to a government censor.

- Criticism and Nickname: The Act earned the derogatory nickname “Gagging Act.”

- Its most troubling aspect was the discrimination it exhibited between the English press and the vernacular press, and it provided no right of appeal in a court of law.

- Impact on Vernacular Press: The Act led to legal proceedings against vernacular newspapers such as The Som Prakash, The Bharat Mihir, The Dacca Prakash, The Sahachar, and a few other newspapers.

- It effectively achieved its goal of stifling the tone of the vernacular press, leading to a lack of originality in thinking, with vernacular newspapers often borrowing content from the English press.

Revisions to the Vernacular Press Act and its Repeal

- Removal of Pre-Censorship Clause: In September 1878, following objections from Lord Cranbrook, the new Secretary of State, the pre-censorship clause of the Vernacular Press Act was removed.

- A Press Commissioner was appointed instead, tasked with ensuring the accuracy and authenticity of news for the press.

- Repeal of the Act: The Vernacular Press Act was eventually repealed in 1882 during the tenure of Lord Ripon.

- Ripon, a nominee of the Liberal Government led by Gladstone, believed the circumstances that had necessitated the Act in 1878 no longer applied.

Surendranath Banerjea’s Imprisonment (1883)

- Event: In 1883, Surendranath Banerjea, a prominent Indian journalist, became the first Indian to be imprisoned for his writings.

- Reason for Imprisonment: Banerjea was jailed due to an editorial in The Bengalee newspaper, where he criticized a Calcutta High Court judge for his insensitivity to the religious sentiments of Bengalis in a court judgment.

Enroll now for UPSC Online Course

| Must Read | |

| Current Affairs | Editorial Analysis |

| Upsc Notes | Upsc Blogs |

| NCERT Notes | Free Main Answer Writing |

Conclusion

The early nationalists’ struggle for press freedom was a pivotal chapter in India’s fight for independence.

- Despite numerous legal challenges and censorship, their efforts laid the foundation for the press’s role in mobilizing public opinion.

- The eventual repeal of the Vernacular Press Act in 1882 symbolized a victory for press freedom and the nation’s growing resistance to colonial rule.

Sign up for the PWOnlyIAS Online Course by Physics Wallah and start your journey to IAS success today!

GS Foundation

GS Foundation Optional Course

Optional Course Combo Courses

Combo Courses Degree Program

Degree Program